Jasmine Johnson

b. 1985, Brighton

2011-2014 MFA Fine Art, Goldsmiths, London

2004-2007 BA Fine Art, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham

Recent Exhibitions

Solo shows:

2015 ‘Third Party ASI’, CCI Fabrika, Moscow

2012 ‘Glory Days’, AC Institute, New York

Group shows:

2015 ‘#3’, Atomic Pictures, Paris

2014 ‘21st Century Graduate Screening’, Chisenhale Gallery, London

2014 ‘Space of No Exception’, CCA Sokol, Moscow

Awards and Residencies:

2015 Step Beyond Grant, European Cultural Foundation, Moscow

2013 Annual Fund (jointly awarded with MoreUtopia!), Goldsmiths University of London, London

2009 Public Arts Programme Commission (jointly awarded with Marianna Simnett), Docklands Light Railway, London

Artist’s Statement

Central to Jasmine Johnson’s work is the defining of utopias and utopian thinking which includes studying the nature in which lifestyles are reproduced. Often taking cues from portraiture and methods in anthropology, she identifies and mediates individuals, activities and objects for their capacity to articulate human anxieties and proximity to global dilemmas.! !

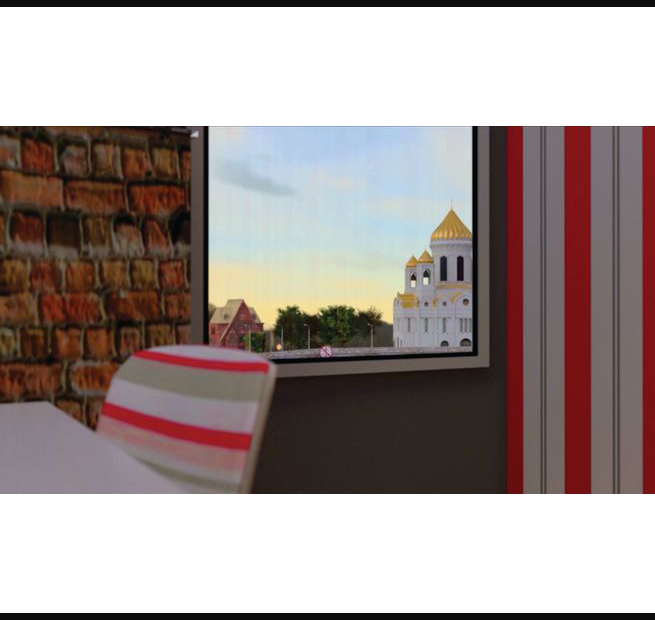

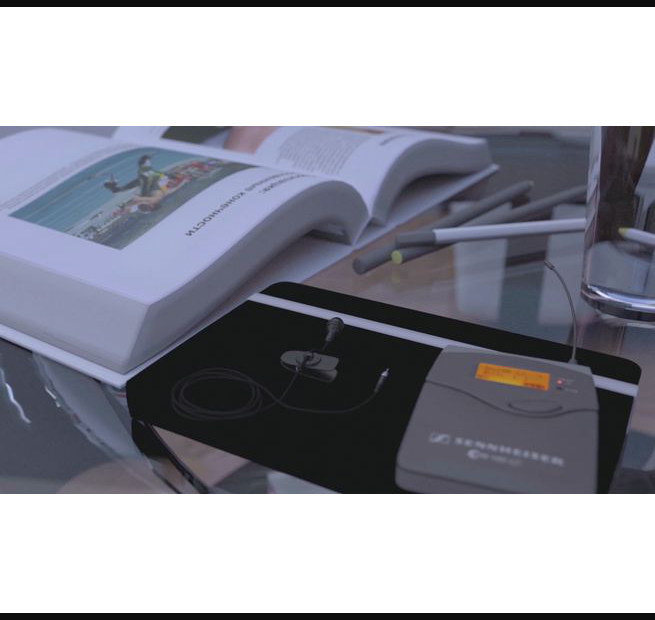

In the 9 minute video, Thieves and Swindlers are not Allowed in Paradise, a camera pans impossibly smoothly from a computer screen through the uninhabited but active central Moscow office of a collector of naive art and a campaigner for life extension. Outside the window, stands The Church of Christ the Saviour, where we are informed Pussy Riot protested. The anthropological tools of the artist - sound recorder and headphones, notebook and pens, sit amongst high end furniture and glassy finishes, hinting at the means of production. The walls are festooned with paintings including those by the utopian naïve artist Pavel Leonov, who himself referred to his paintings as rooms or film sets. The jarring perfection becomes identifiably digital, and moments of synchronicity between a disembodied voiceover and image fix an otherwise outwardly expanding narrative. We see an intricately rendered wood floor and hear that you can spot an imitation artwork because it has a lack of heart. Collecting becomes synonymous with the realm of digital images, capturing every detail becomes fastidious, but also lifeless. The visibly oppressive economic, political and social power structures weigh heavily against the dissident qualities of activism and the outsider. Then we cut to a handheld camera in the riverside home of a British collector where the rural Russian paintings have a different resonance. As the edit and framing of the monologue moves from propaganda, through news broadcast to radio play, context shows itself to be vitally important in the telling of stories.