Circumnavigating the Patriarchy

Women's Collectives

Ahead of our event Women Working Collectively, What is Your Value?, artist, writer and activist Rose Gibbs, part of The Temporary Separatists, explores the history of women’s collectives and their continuing importance in an increasingly globalised world.

In December 2015, we host several events related to feminism, including Now You Can Go, Feminist Practices in Dialogue and a symposium on women's filmmaking in contemporary Britain.

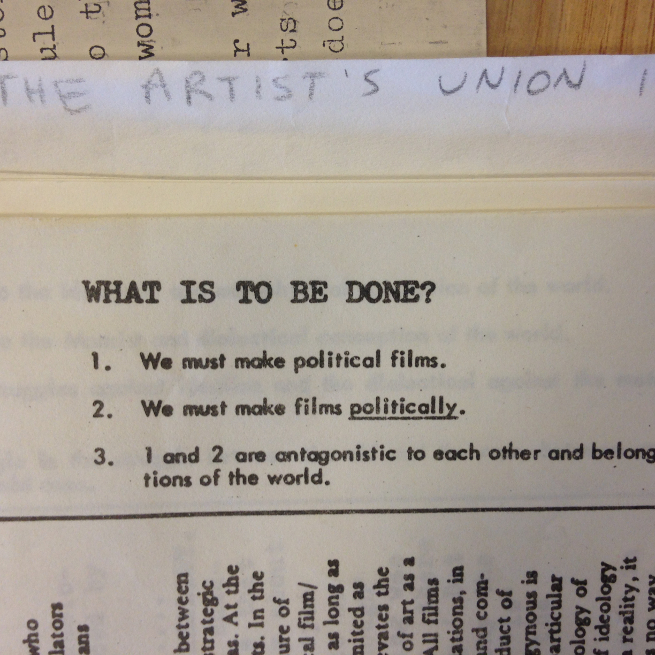

Feminism is a movement at war with itself: it is both a method of recognising gendered group treatment, and also an attempt to find a route to autonomy and liberation from such categorisation. The first objective seeks to unite and bring people together in solidarity with one another—to recognise the political in the personal—while the second attempts to probe the validity of such groupings. It is the oscillation between these two seemingly contradictory aims that make feminism such an interesting and rich ideology through which to view the world: one that leaves us with no easy answers and elicits an active engagement with situations as they arise, calling forth thought and analysis, rather than the uniform and dogmatic application of neatly concluded formulae.

As things stand, gender continues to dominate both economic and cultural spheres. In light of this, calls to abandon the gender binary might seem like a good idea. Yet, given that there is no doing away with biological sex, the assignment of normative gender binaries will most likely continue in mainstream culture. Progress toward recognising or living out gender as set of varied characteristics that exist upon a spectrum will be slow.

Moreover, with the advent of globalisation and post-Fordist capitalism, sites in which to gather and protect individuals against exploitation are withering away. In these circumstances it is not hard to see the dissolution of gender as part of the agenda of the atomising individualism that is at the heart of neoliberal capitalism. What if this blurring of boundaries does not liberate biological females and woman-identifiers from their gendered lives, but merely conceals what is actually going on?

In the last 15 years, the art market has become a global phenomenon: commercial galleries operate transnationally. Top selling artists run multiple studios, often across several capital cities in a move not dissimilar to haute-couture fashion brands. In this climate of liquid modernity, anything that threatens to halt or slow the free flow of assets is only begrudgingly accommodated. As such, it is not surprising that claims to gender fluidity, probably more in name than in fact, are frequently put forth by artists and curators alike. As women continue to be discriminated against, to say you are a woman becomes a distinctly political act.

Against this background, women’s artist collectives provide an interesting and feminist alternative to individualistic artistic practice, aiming not to infiltrate or recreate patriarchal hierarchies but to circumnavigate them.

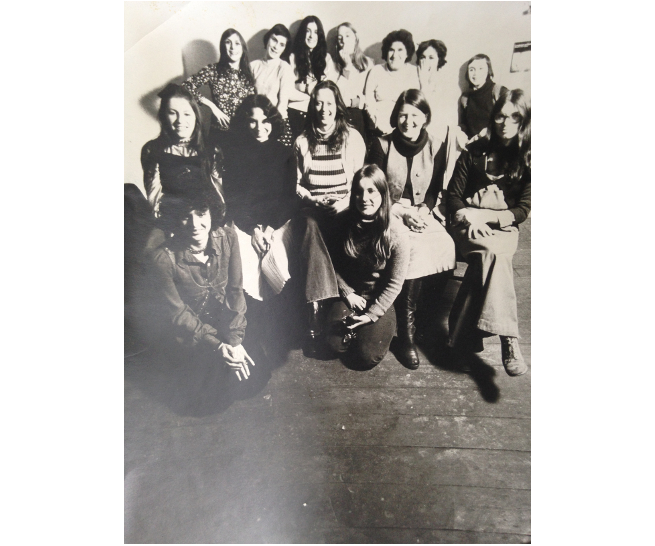

Many examples of such collectives can be seen in the women’s movement of the 1970s, born out of the anti-establishment spirit of the day: being a feminist was part of a broader interrogation of traditional systems and structures, with an ideological trajectory starting with personal aspects, like the family unit, and spiralling outwards towards systems of government.

Such collectives were rooted both in gender and in place. The Women’s Free Art Alliance, founded by Kathy Nairne and Joanna Walton in 1973 was set up with the intention of facilitating workshops where women’s self-development and creativity could be explored and expressed. The WFAA managed to find a space, as well as a grants to fund its program, thus was able to provide a site for other women’s groups to meet and also a food co-operative.

In 1975, the WFAA organised the women-only exhibition Sweet Sixteen and Never Been Shown. Such initiatives were radical in their approach to exhibition-making: this exhibition was open to all women. There was no entry criteria, artists were not expected to have an art education background, nor a track record of prior exhibitions.

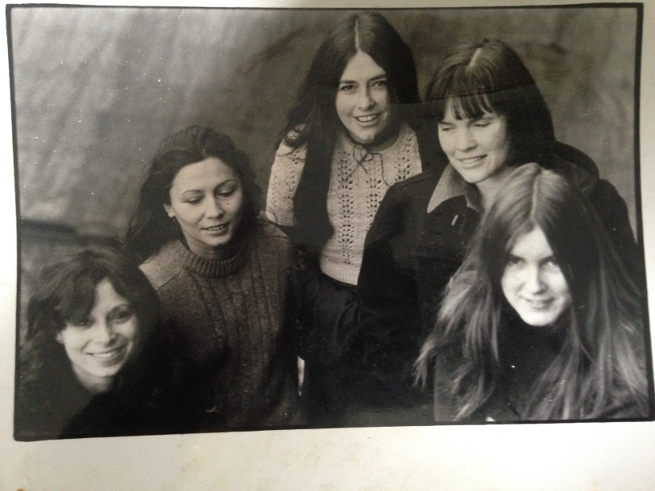

In the absence of acknowledgment from institutions, other groups like The Women’s Artist Collective provided a forum in which to not only discuss member’s work, but also that of women throughout history. They talked about themselves as artists, as feminists, as women, asking if there was such a thing as women’s art, and attempting to discover their own language, away from that of the patriarchy.

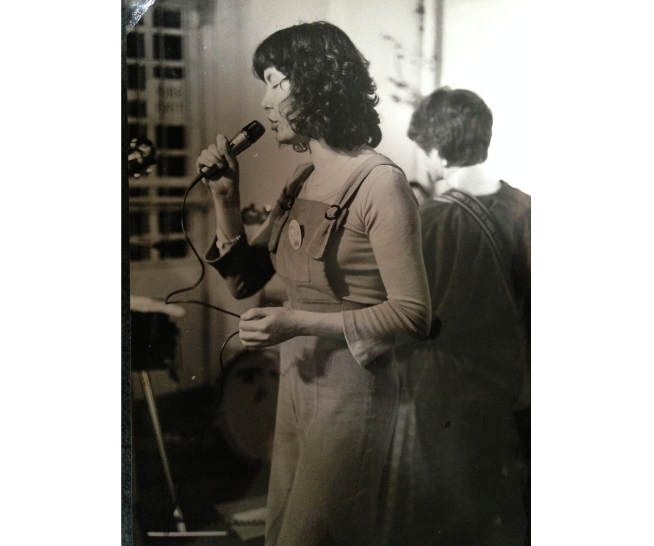

Making shows in independent spaces was integral to the effort to create an alternative to the gallery system, which was perceived as part of the hierarchical establishment that these groups were fighting. The energy that they created, as well as protests outside exhibitions like the Hayward Annual in 1977, paved the way for the beginnings of institutional change.

The Hayward adjusted its quota of women artists the following year (though this was not to last), putting on an exhibition known as the Women’s Annual with 16 women and 7 men. Similarly, it was a protest against the exhibition of Allen Jones’ work at the ICA in 1978, organised by Nina Jennings, that sparked the conversations that lead to the three women’s shows at the ICA from 1980. The first show, Women’s Images of Men broke all attendance records, averaging 1000 visitors a day, with a queue running from the ICA to Trafalgar square.

Many of these collectives evolved over time, with members changing and working within several collectives simultaneously. Though comprised of a core group who met on a regular basis, the collectives extended their support to women beyond their immediate circle. This not only included self-identified artists whose work they showed, but also women’s causes more broadly. The Women’s Workshop of the Artists Union initiated contact with the strike at Brannans, the Fakenham Occupation by women, and the Women Night Cleaners Campaign. Such initiatives evolved into art projects like Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry 1973-1975, a collaborative work by Kay Hunter, Mary Kelly and Margaret Harrison documenting women’s work in a metal box factory in Bermondsey in London.

There are a great a number of women’s art collectives from the 1970s which demonstrated an alternative approach to art practice, from Feministo – The Postal Art Event, to the Hackney Flashers and the Birmingham Women’s Art Group, to name a few. Within these collective practices, the value of art was found in community and communication, rather than in commodity. ■

Women Working Collectively, What is your Value? takes place on 9 July at 6.30pm, a discussion exploring whether women’s artist collectives can offer resistance to the atomising individualism of neoliberal capitalism that is at the heart of current global art markets.

In December 2015, we host several events related to feminism and gender, including Now You Can Go, Feminist Practices in Dialogue and a symposium on women's filmmaking in contemporary Britain.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events

Tagged with: Feminism, Patriarchy, Women's Collectives, Rose Gibbs, events, learning