The Legacy of Mighty Sparrow

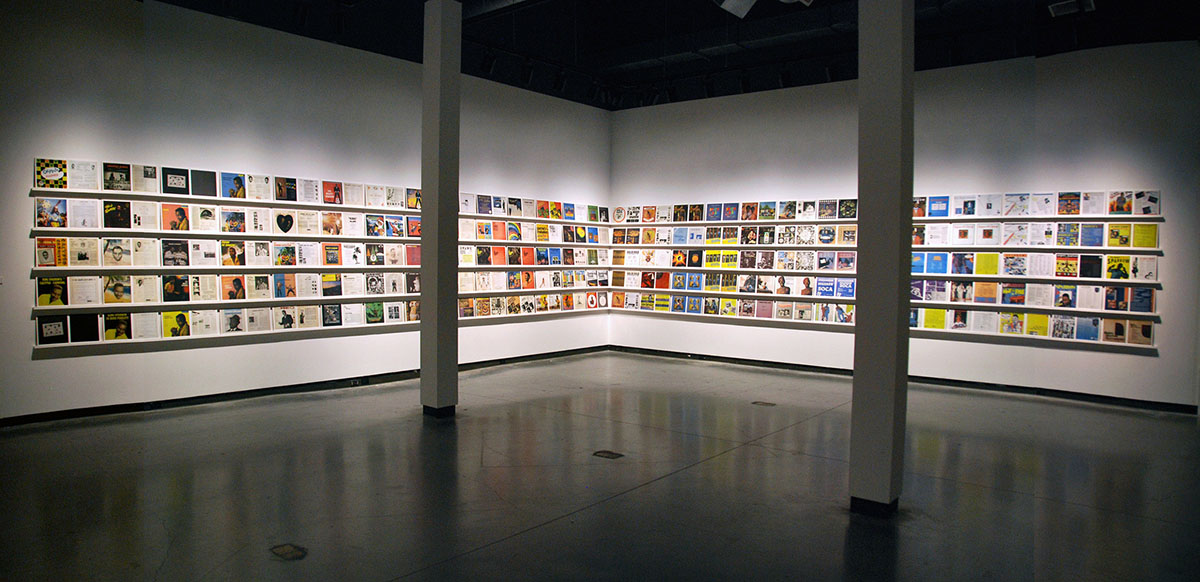

Sparrow Come Back Home, British artists Carmel Buckley and Mark Harris's exhibition of 288 ceramic tiles celebrating calypso singer Mighty Sparrow's life and work, is currently on display in the ICA Fox Reading Room. Here they discuss the work and ideas that culminated in this exhibition.

Sparrow Come Back Home culminates at the ICA after a long road. From starting work in 2010 with a visit to Trinidad to record sounds and talk with relatives (Mark's mother was Trinidadian), six years later we are delighted to see it in full form at the ICA.

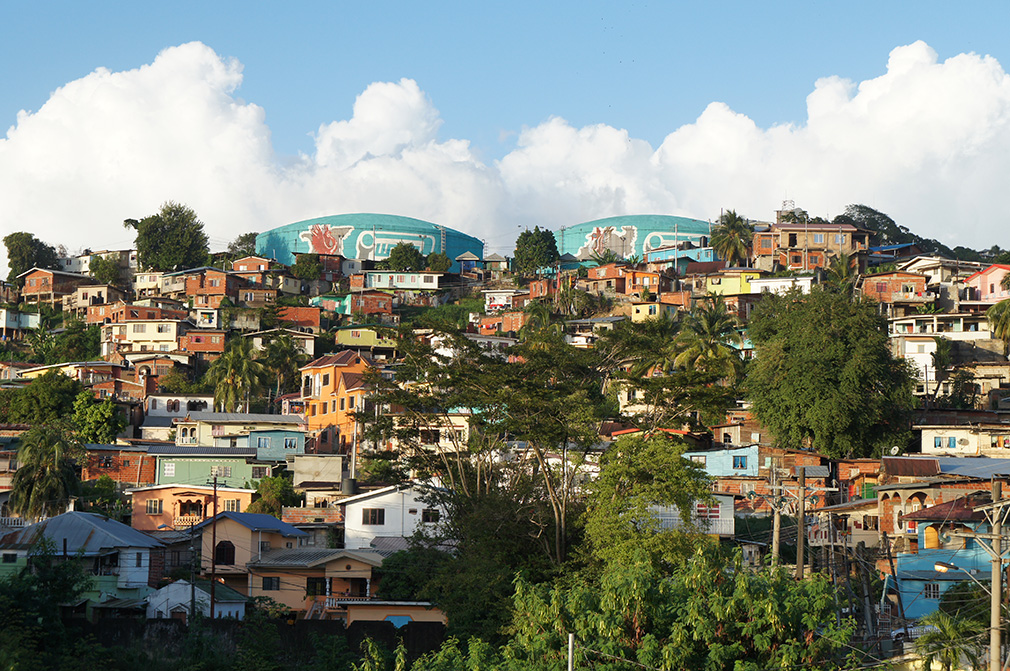

Mighty Sparrow grew up as Slinger Francisco in Laventille, an economically-deprived district in Port of Spain and the subject of his early calypsos about the challenges of living in extreme close quarters (Mr. Herbert) or of encountering local gangs (Gunslingers, Ten to One is Murder). Our research started with an outdoor installation for Sculpture Key West, in Florida. We were familiar with calypso through Mark's mother’s collection of Sparrow records and knew there was limited awareness of Sparrow’s output in the States compared with other World Music, such as Cuban Musica Tropical. With Key West being the closest US location to Cuba, we imagined an atmosphere of calypso music mixing with sounds wafting up from Trinidad. We hand-made 20 tiles, fired them with decals of Sparrow’s record covers and installed them in a botanical garden. Sparrow’s music, interspersed with sampled sounds we recorded in Trinidad, played in the background.

As the handmade versions looked a bit rough, with the decals losing some of their precision, we thought we’d try another batch on commercially-produced glazed white tiles. There was already the idea of substituting something permanent for vinyl records, like a monument or memorial. The archiving and historicizing of Trinidadian music has been very erratic; although it’s not difficult to find Sparrow’s records, it’s all but impossible to find out about pre-1950s music, let alone acquire examples of it. Hardly anything has been re-released – sometimes it seems as if that musical culture has vanished, along with documentation of the Trinidad Carnivals for which those calypsos were sung in the first place. The invitation in 2014 to install a new version of the exhibit at the Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts in Wilmington gave us the incentive to include tiles representing as many of Sparrow’s records as we could find, and really turn this project into a comprehensive commemoration of his life’s work. It’s that version that has been adapted for the ICA, and supplemented with the timeline, archive, audio components and essay on Sparrow.

Popular music and record design are rarely accepted institutionally as a part of cultural research and history.

But why ceramic? The decision to make the piece out of clay tiles always felt a bit of a challenge, given the labour-intensive fabrication process and the cumulative weight. This sense of permanence relates them to the music’s vanishing historical trace, and the tiles are close enough to the size and thickness of a 12” record cover to double at first glance for their vinyl counterpart. Even though the raw tiles of this final version were industrially-produced and came glazed white, each had to have the digitally-printed decal manually transferred to the tile’s surface before being kiln-fired, making the image permanent. Carmel did this work at the University of Cincinnati, with a lot of help from Katie Parker and Guy Michael Davis, fellow faculty of Mark’s.

Popular music and record design are rarely accepted institutionally as a part of cultural research and history. At best they end up in a rock and roll hall of fame or a museum show on a musician. Converting the 12” covers to tiles enables records to infiltrate contemporary art galleries and museums where different contexts are brought to the images and the lyrics. With the Sparrow show we installed last summer at Cincinnati’s Clay Street Press we started an archive that included literature by Earl Lovelace and Derek Walcott.

Although we aren’t deliberately making statements about race, we’re intrigued by the implications of giving space in a gallery to the achievements of a person of colour. You walk into almost any gallery and depictions are invariably of eminent white historical figures. Even Dominic Molon’s show on rock and roll at MCA, Chicago, Sympathy for the Devil, was mostly about white music. Sparrow Come Back Home celebrates the achievements of a black singer in the format of a museum display that references both record store and monument. In Wilmington, after New York rapper Shan Shizzy did a promo video in front of the installation, it became clear to us that to African American audiences there was something unexpected about this emphasis in a contemporary art centre on the achievements of a person of colour.

We’re intrigued by the implications of giving space in a gallery to the achievements of a person of colour.

The fiercely-contested culture of the last 150 years of the Trinidad Carnival has engendered some of the most linguistically creative, witty and downright beautiful music ever made. Sparrow has consistently pushed the boundaries of that inventiveness. We’d be delighted if this exhibition enabled others to find their way into enjoying this music and its rich ideas. ■

Sparrow Come Back Home is in the ICA Fox Reading Room until 5 February.

This article is posted in: Articles, Exhibitions

Tagged with: Sparrow Come Back Home, Mighty Sparrow, Calypso, Mark Harris