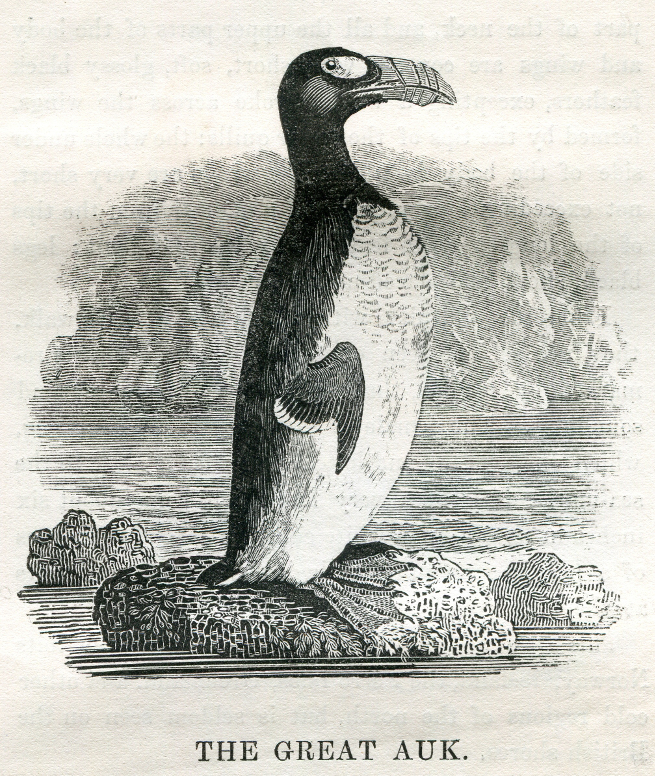

The Decline of the Great Auk

An Interview with Jessie Greengrass

Author Jessie Greengrass, recently nominated for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, spoke to Abi Bryant and Maya Caspari about her award-winning short story collection An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, philosophy and the art of short story writing.

What prompted you to start writing the stories in your collection An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk? Did your background in philosophy shape your choices?

The immediate starting point for each of the stories varied - with some it was a phrase, with others an image or a sense of voice, a feeling of a person in a situation. Quite often the original thought ended up being not terribly important in the finished piece - with the title story, for example, it was the fact that for years after the final great auk colony had collapsed and the last known breeding pair had been killed there were reports of lone birds being sighted at sea, just floating about, as if they were looking for the rest of their species. It seemed such an evocative thing, these desperately lonely birds, absolute remnants, searching - but in the end I couldn’t find a way to fit it into the story.

"Most of the stories end up being about personhood: about how it feels to be trying to give an account of something when all you have is your own experience of it."

Beyond that, each of the stories seemed to offer a way to get at something particular that I wanted to articulate. At the time I was thinking a lot about personal identity so most of the stories end up being about personhood, particularly the subjective experience of personhood: how it feels to be trying to give an account of something when all you have is your own experience of it, how hard it is to describe that and make it explicable to someone else. My first engagement with these kinds of subjects was when I was studying philosophy and during that time felt immediately real to me. It felt as though there was a reality to these problems that wasn’t about trying to solve them but was about the experience of them- about how it feels, for example, to acknowledge the problem of other minds, or the nature of consciousness, not just as theoretical problems but as ones which relate to your own mind and your own body and your attempts to find a place in the world, to live in it in an engaged way.

What especially appeals to you about the short story form? How does it shape the writing?

It’s an interesting thing, being a writer who hasn’t formally studied literature in any way, because I quite often don’t feel up to the task of talking about my own work. In terms of the length constraint, working over a short stretch forces a particular kind of clarity on me: there’s only space for one idea so I have to be sure what it is, and then anything extra, anything extraneous or not to the point, even down to individual words, has to be cut away, until hopefully what’s left feels unitary. The clearest example of what I mean that I can think of is David Foster Wallace’s Suicide as a Sort of Present which I think is an extraordinary story in that it always feels like it’s an absolute totality, like it came in a single piece. The best short stories, I think, are ones which feel like that and also which are transparent, so that you can see exactly how they work, like a watch with the back taken off, and all the cogs fit together.

"The best short stories, I think, are ones which are transparent, so that you can see exactly how they work."

All this means that when I’m writing a short story I tend to think in terms of argument, as if I were writing an essay. The point of the story is a hypothesis and the story itself is an attempt elucidate it - the shape of the story always feels to me as though it’s dictated by the argument, and that’s quite appealing because you don’t have to try and bring disparate ideas together and it’s always very obvious when it’s finished. More pragmatically you don’t have the same readability constraints with a short story as you would with a novel- you can use a strong voice because it’s fine if you’ve got a really irritating narrator for ten pages, much less so if the reader has to suffer it for a whole book.

The stories seem to share an engagement with estrangement and loss. Though many of the narratives are first-person, the syntax and use of language creates a sense of disjuncture and unfamiliarity. What was behind this?

I’d like to say that this was on purpose but I don’t really think on this level when I’m writing. My best guess is that it comes out of the fact that I was interested in people who were struggling with the idea of mental privacy - which is as lonely as it is liberating. It wasn’t so much the events described in any of the stories which interested me as the attempts of the narrators to describe them and the way that they are constantly coming up against their failure to be able to make clear what they want to make clear, or to prove what is, essentially, unprovable.

"You are constrained by your own perspective - you can’t get beyond that to make a direct connection."

There’s a line from T S Eliot ‘“That is not what I meant at all;/ That is not it, at all.”’which has always sounded to me like a howl of absolute despair at not being able to find a way to explain yourself, not being able to make yourself understood because you are constrained by your own perspective, you can’t get beyond that to make a direct connection. I think this line could be appended to pretty much any of the stories in the book (with the exception of the last one). So if the language seems to create a kind of disconnection it’s because all these people are trying to use language to do something that, ultimately, it can’t do, so they are disconnected, they are isolated, and they haven’t found a way to reconcile themselves to that.

Though there are common thematic strands, the stories in the collection are set in a variety of locations and in different eras. Was this a conscious choice? Did you conceive of the stories as a collection while writing them?

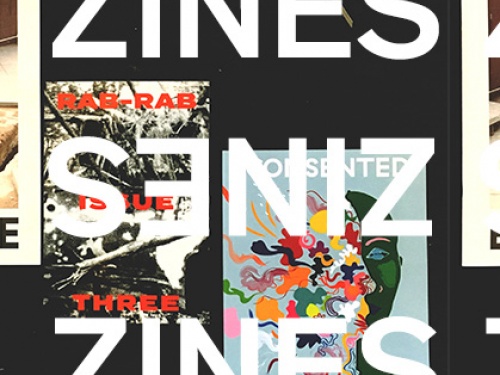

The fact that all the stories occupy the same general territory is just because that’s what I’m interested in - I didn’t think of them as forming a collection, and never really intended them to, which is probably why their specific subject matter is so wide-ranging. Most of them I wrote because some friends and I ran a sort of zine for a year or so, and after we’d made each one we’d think of a subject for the next one—very general subjects like “boats”—and then all go away and write something. It was lovely, and fun, and also an excellent way of being forced to get on with work that I can heartily recommend.

Which writers have influenced you? Are there books or authors you would recommend to visitors of the ICA bookshop?

I’ve actually read very little for the past few years. I find it really hard to read when I’m writing - the voice I’m trying to use for any given piece of work is pretty fragile and whenever I read anything else it tends to seep in, usually with pretty excruciating results. Also I have a young child, and so it’s also difficult to find time between keeping my own stuff going and general wear and tear on the mind from childcare. My literary touchstones—things I come back to over and over again—which I could never claim as direct influences but which sort of echo constantly through what I’m thinking, are writers like John Donne, his sermons as well as his poetry, the incredibly measured pace of it, the way he moves through argument to conclusion. I’m a big fan of Phillip Larkin, too, and, in a similar vein, one of the books I read over and over again is Louis MacNeice’s Autumn Journal, which always seems to have a bit of commonality with whatever happens to be going on in my life at any point.

"The voice I’m trying to use for any given piece of work is pretty fragile and whenever I read anything else it tends to seep in."

I’ve recently been thinking about Sebald quite a lot, and some of the texts that I’ve got to through him—Thomas Browne’s Hydriotaphia, for example—and also about M John Harrison’s early novel Climbers. I’m endlessly fascinated by pretty much all of Harrison’s work but Climbers feels pertinent: it’s a novel in which the events are secondary to the mapping of the protagonist’s experience. It creates an extraordinary sense of being at sea within the narrative which somehow never stops you from feeling engaged as a reader. It’s a brilliant trick and I wish I knew how it was done.

I’d also, in a nod to my daughter, recommend even to those without children the work of Jon Klassen. It feels to me as though something is happening in books for young children at the moment—as though they’re becoming a form in their own right—and Klassen is at the forefront of that. His two (soon to be three) hat books and also Mac Barnett’s Sam and Dave Dig a Hole, which Klassen illustrated, strike me as being satisfying in exactly the way that the best short stories are: economical, elegant, well-made. ■

An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk is available in the ICA Bookshop.

This article is posted in: Blog, Interviews, Store

Tagged with: Jessie Greengrass, Abi Bryant, Maya Caspari, An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, Short Stories, Philosophy, poetry, Literature, ICA Bookshop