The Weekly Rewind: Twelve Weeks of fig-2

Writer, curator and critic Chris Fite-Wassilak reflects on the first twelve weeks of fig-2 for the ICA Bulletin.

A vinyl record is spot-lit at the back of the darkened space. Two screens depict a surreal, jerking, black and white video, the protagonist of Hiraki Sawa’s Lineament (2012) trapped in a room where animated record grooves become clothes threads become thought lines become film spools and back again.

The scratching and cello throb soundtrack of the film comes from the vinyl – the video ends, the needle reaches the centre of the disc, and it slows its clockwise turn. Stops. And begins turning again in the opposite direction. The video recommences, but despite things apparently running backwards, the soundtrack plays just as before. Dale Berning and Ute Kanngiesser’s score for Sawa’s video is a palindrome, as if simply shrugging off time itself. We’re left somewhere in this temporary time warp. This is three weeks into fig-2, but the time-trap feels appropriate given that the project as a whole is a return to fig-1, staged in a room in the now-demolished Fragile House on Duke Street in 2000.

Winding backwards to 2000 London is a particular choice. An exhibition-a-week framework these days could cite any number of precedents, whether the ICA’s own six month Nought to Sixty programme in 2008, or, as Dan Fox noted in his review of fig-1, Matt’s Gallery’s one-week shows in the 1970s, as well as their more recent Revolver series, or indeed, the everyday schedules of any number of project and artist-run spaces that, through necessity or otherwise, have quick turnarounds. But harking back to new millennial London gives it a certain haze; most attendees of fig-1 speak of it in glowing terms, with a faraway look in their eyes: it was focused, fun, experimental, where people got together to kick off their week.

fig-1 seems definitely of its time: a turning-point when the ferment of artistic activities in the city was gaining momentum and wider attention (to which we should also add: commercial interest). fig-1 wasn’t a commercial venture, though run by curator Mark Francis (soon to be appointed director of Gagosian’s Britannia Street branch) and supported by Jay Jopling (who, in 2000, had just shifted his gallery from James’ Street to its new Hoxton Square premises) and Bloomberg. You might say it was a pretty smart loss leader, or, to be anachronistic, a Kickstarter campaign for its time.

The list of those who took part in the original is what accounts have called a mix of established and then-unknowns; looking at it now is to survey a roll call of what are blue-chip and museum-certified practitioners. Here we are, fifteen years later, looking back to a point in London that is, as some have pointed out, pre-Tate Modern, pre-Frieze fair – but also also pre-Hans Ulrich Obrist’s arrival at the Serpentine, pre-Facebook. Beyoncé was still part of Destiny’s Child. So, to ask the rhetoricals: what does it mean to make a sequel to this? Why now?

Part of it is perspective: in an article Carol Bove wrote recently giving advice to artists, her reading list includes: "Fifteen-year-old art magazines: Fifteen years is about half of a fashion cycle, so you see artworks in their least flattering light." Another part is, of course, funding: it was philanthropic organisation Outset that spurred on the revival. Support for curator Fatoş Üstek this time around has come from a odd mix of private support and entities like Phillips auction house and the Oxfordshire ‘chic outlet’ Bicester Village. fig-2 is, so far, also focused, fun and experimental; but the context in which it is happening is a bigger, more varied city than fifteen years ago – as well as more cynical and faster-paced. (Imagine what they might be saying in another fifteen years when fig-3 rolls around – it was "pre-the Tate Modern Project extension, back when culture and the NHS were at least still partially publically funded.")

The defining feature of the fig series is its structure and rhythm, and while each week is different, providing a short-term platform for new and unfinished works gives it the overall tone of a music demo – you look more for the ideas, the inclinations, its reach than for any end in itself. An actual answer to those questions might have to be provided by fig-2 as it unfolds over the rest of this year and we might see the imprint that remains once it’s finished. That demo tone is also telling us to just shut up and pay attention. Trying to generalise about a large range of practices that have already been on show this year is not only futile but inconsiderate. Yet, what the first twelve weeks might cumulatively suggest is: look harder, because the now is all we have.

"I’ll escape if I try hard enough," was a mantra repeated as part of the Gaggle performance with Michael Shaw, Echo, Echo, Echo during their week in the studio. If there’s something that did actually seem to span across these first few weeks of fig-2, it was the attempt to get away from the ‘everyday’. But getting beyond it by going through it, burrowing into it, whether with Sawa’s repetitive loops, Simon Welsh’s cheesy rhyming couplets of mundane transcendental encounters, Edmund Cook’s computer mouse-like objects, cast as impossible thought-recording devices, Tom McCarthy’s contemporary flaneur anthropologist who tries, in Satin Island, to piece together his random encounters, or Young In Hong’s elaborate disrupted dinner-party performance In Her Dream (2015). These are projects trying to pin down the normal and mess with it until it sings, bleeds, or gives up the ghost entirely.

Say, for example, the art of small talk with strangers: Annika Strom’s Six Lovely People (2015) was just that, but as one of her interactive performance pieces involving actors, just how lovely depended on the circumstance. I had been assured that the packed opening Monday event was "great fun"; I made it in during the week, when the ratio of lovely to normal was six to two. Walking into the studio, all heads turned, assessing me as the next victim. It probably says more about me than anything else that being surrounded by a group of actors who all want to talk to you is my idea of the eighth sphere of hell, but it was only slightly less painful than any other awkward party where you don’t know anyone. Here, the small talk turned to the nature of being paid to be nice to people; my lovely assailant conceded that he had, actually, lost sleep thinking about it. I might’ve, at least for the sake of journalistic investigation, tested his loveliness with extreme curmudgeonliness, but the proximity to a real, humdrum conversation was too much for me; I fled. Sorry.

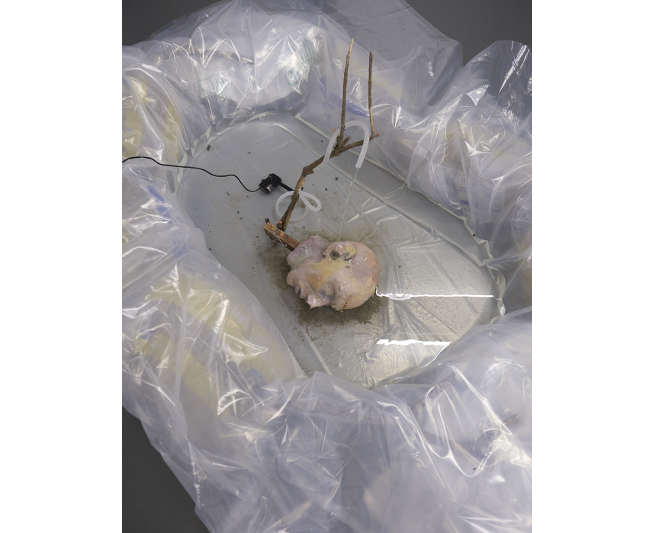

Given all the parameters—a fairly small space, a fairly short time—where the project seems find its traction is in uncertainty. Actual uncertainty: half-figured out arrangements being tested on an audience, mumbled pronunciations and temporary leanings, these are the things that each week might prospectively offer, and that we have the duty and the pleasure to look out for, because you don’t get the chance to really see them very often. (Or, rather, more often we get the affected, pinned-down butterfly version.) This is what made Beth Collar’s ramshackle DIY fountain seem like one appropriate monument for fig-2 so far: some plastic sheeting thrown over a few bags of concrete and a limp stream of water running out of tube wrapped around a twig. The water runs into the ear of a head made out of what looks like clay, slowly disintegrating in the constant stream.

Another, even more temporary monument, might have been the layers of scribbled transparencies projected onto the ceiling and a few improvised plaster screens for Rebecca Birch’s performance Lichen Hunting on the West Coast (2015). "This isn’t really about the stick," Birch herself attested, while still using the lichen-covered stick she had found years previously as a MacGuffin to lead us from Corby to Greenock and out to the Taynish rainforest on the west coast of Scotland. The hurried outline marker drawings on the transparencies, illustrated each moment that Birch narrated, accumulating over the talk to become a tangle of discarded moments; we know where we’ve come from but it's a path impossible to follow back. Like Gaggle’s Echo, the almost innocuous phrases "crows crows crows", "the power of money," or (my favourite) "I like guitars – and cigarettes", were repeated, shouted, recorded and replayed, until the studio became a spiral of concentrated noise, our mundane words turned into a hurricane. It’s in between these layers, spirals and disintegrations that fig-2 gives us examples to find. ■

fig-2 runs for 50 weeks in the ICA Studio, presenting a new project every week.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Exhibitions

Tagged with: Chris Fite-Wassilak, fig-2, fig-1, Fatos Ustek, Beth Collar, Hiraki Sawa, Gaggle, Michael Shaw, Rebecca Birch

/index.jpg)