From the Archive: Shapes and Forms

Ahead of the screening of Mark Aerial Waller's The Sons of Temperance and George Hoellering's Shapes and Forms—the first example of the ICA on screen—PhD candidate Lucy Rose Bayley explores the signficance of the films for the ICA Bulletin.

In the Tate Britain Archives there is a collection of transcribed interviews led by Dorothy Morland, ICA director 1968-1977, with artists, staff and committee members of the ICA including Richard Hamilton, Toni Del Renzio and Julie Lawson.

Called Reminiscences, they capture anecdotal histories of early exhibitions and events. In reflecting on their memories of the early years of the institution, a few recall the impact of the ICA’s second exhibition 40,000 Years of Modern Art (1949), advertised as a confrontation between modern and primitive art. It is in these interviews that I found reference to a film that had been made of the exhibition by Austro-Hungarian filmmaker and founding member of the ICA, George Hoellering.

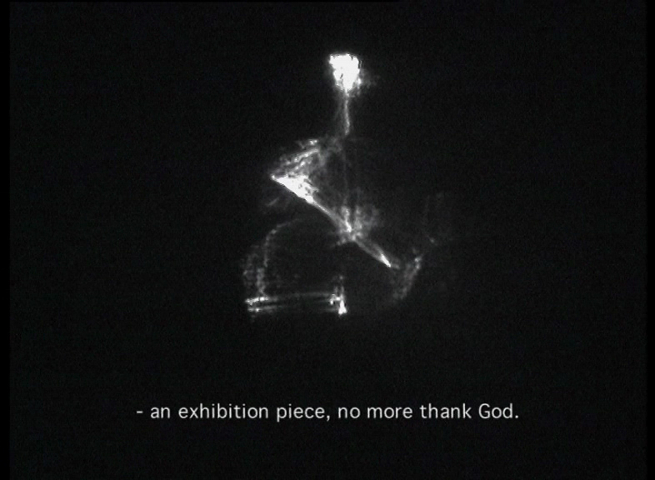

Entitled Shapes and Forms, it is, I believe, the first example of the ICA on film. The exhibition was held in the basement of the Academy Hall Cinema in Oxford Street, which George Hoellering managed at the time. Over one night he created the film with the assistance of Roland Penrose. Now in the collection at the BFI, the film captures spot-lit objects rotating and emerging in and out of the darkness, accompanied by a modernist composition by Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist and conductor Lazlo Lajtha.

"There will be no lecturing to distract you. Aided by the music, the camera will be your guide on this journey through an enchanted world, where the human imagination blossoms out luxuriantly in the shapes and forms of art."

The film begins with this instruction. Slow down, listen to the music and appreciate. Then come the objects: details of Wilfredo Lam’s Anunciation, Alberto Giacometti’s Figure 1936. The camera tracks across Barbara Hepworth’s, Figure 1931 (now in the Pier Art Centre Collection) and to a spinning shot of Figure, made in wood from the Baga tribe in French Guinea (now in the British Museum collection). There’s a brief interlude before returning to the same dark and light undulations.

Viewing the film today, we reflect on ownership: where are the works and who owned them, then and now? Though the exhibition installation was highly original, designed by FHK Henrion with a winding pebble pathway and plywood cabinets, the film ignores this and instead reflects a traditional museum display where spotlights create dramatic shadows behind objects. Voices and opinions are removed, leaving sound animating shadows in their place, inviting you to take a journey into your unconscious. Its striking aesthetic of sculpture in movement has been reconsidered by artists, occasionally with actual objects from the ICA exhibit re-filmed or re-edited, as with Alain Renais and Chris Marker’s film Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Statues Also Die) (1953), Duncan Campbell’s It for Others (2013) and, less directly, Elizabeth Price's USER GROUP DISCO (2009).

The film is an attempt to read the object in new, detailed light. It reminded me of Mark Aerial Waller’s The Sons of Temperance (2009), in which a secret cult has discovered the ability to read messages hidden within objects through a process of crystal refraction. At the start of the film, a voice refers to the discovery of archaeoacoustics from ceramic objects and the ability to play the ridges made by the potters' hands or tools. It raises the question of whether an object is redundant without its apparatus: even if we can listen to the sounds of an object from thousands of years ago, we don’t have the tools to understand what they say. What will happen if we don’t have the ability to play film in the future? The fear of a redundant object feels ominous. Yet, it is also exciting, opening up potential new ways of reading. Shapes and Forms holds this excitement; it attempts to read the objects in new ways through the camera.

Later in year of the exhibition 40,000 Years of Modern Art (1949), the lawyer, artist, psychologist and author, Anton Ehzenweig presented a talk at the ICA entitledThe Unconscious Meaning of Primitive and Modern Art, attempting to extrapolate historical symbolism and reveal the universality of art. He describes a desire to "document the fundamental identity of archaic, primitive and modern art, whatever the purport of this identity was for a deeper understanding of our culture."

His ideas connect to Herbert Read’s arguments on the difference between shape—as something already existing in the world—and form as the final point of the artist’s trajectory:

"Art does not start from abstract thought in order to arrive at forms; rather, it climbs up from the formless to the formed, and in the process is found its entire mental meaning."

How do we reflect on the mediation of an object, both within and beyond the exhibition, and how does this evolve?

How can we understand the processes of translation, such as the translation of the camera and its dispersal, that surround the public exhibition? ■

On 29 April, there will be a screening of George Hoellering's Shapes and Forms and Mark Aerial Waller's The Sons of Temperance, followed by a discussion between Mark Aerial Waller and Lucy Bayley.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film

Tagged with: Lucy Bayley, Mark Aerial Waller, From the Archive, Sons of Temperance, history, Robert Penrose, Richard Hamilton, Dorothy Morland, Shapes and Forms, George Hoellering, Film, event, Lazlo Lajtha, Archive

/index.jpg)