Welcome Into The Coven of Heretics!

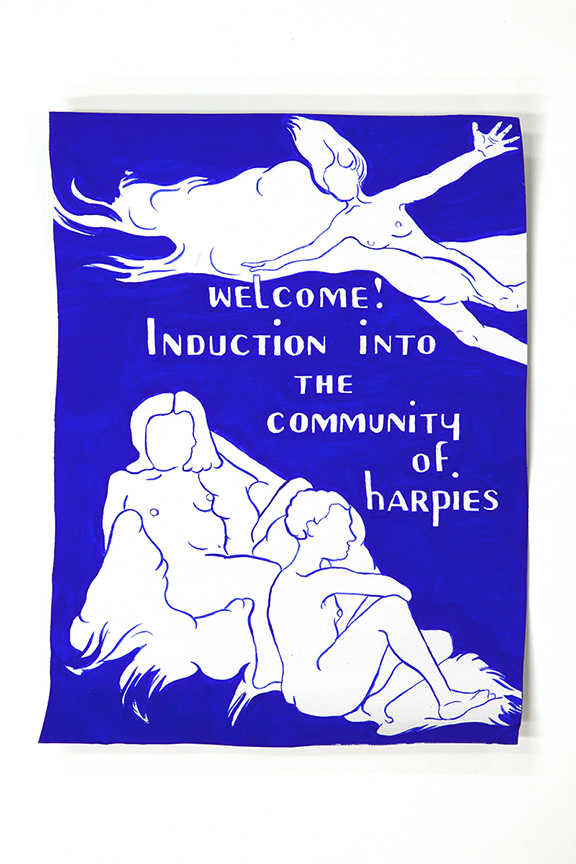

The construction of a witchy collectivity

Bloomberg New Contemporaries artist Anna Bunting-Branch explores witchiness ahead of an evening of live performance, talks and screenings.

In 1969, groups of women armed with broomsticks and clad in black cloaks and pointed hats converged on city streets across the US. The witches danced in circles on Wall Street and ‘zapped’ bank headquarters. They cast hexes upon the University of Chicago’s Sociology Department and descended on bridal fairs in New York and San Francisco.

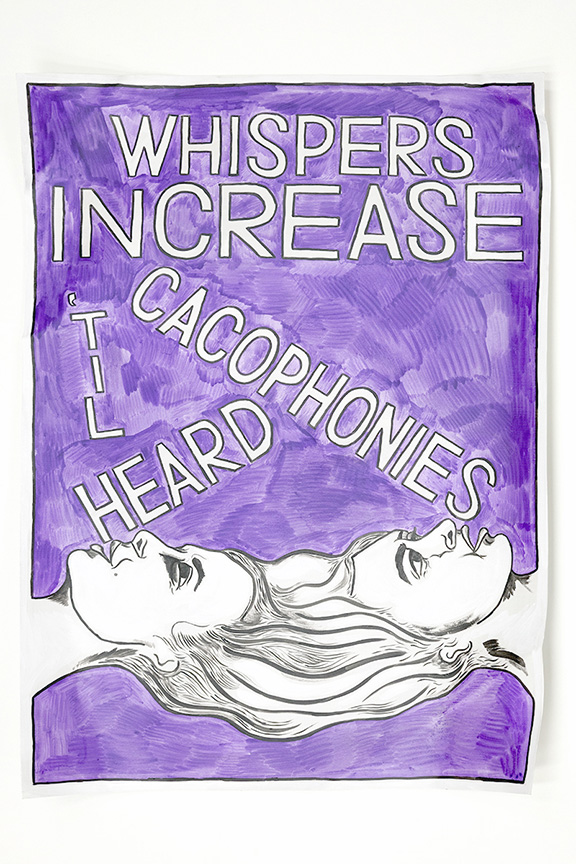

The manifestation of W.I.T.C.H. between 1969-70 is iconic of the movement commonly referred to as “second wave” feminism. W.I.T.C.H. was not a single, homogenous organization. It was a collective vision that was enacted differently by activists within different contexts and communities. Growing out of practices of consciousness-raising, W.I.T.C.H encouraged women to identify shared experiences, acknowledge their collective repression and speak out against oppressive forces – first in private, and then in the public sphere. In this way, W.I.T.C.H. emphasized the empowerment of women through collective action.

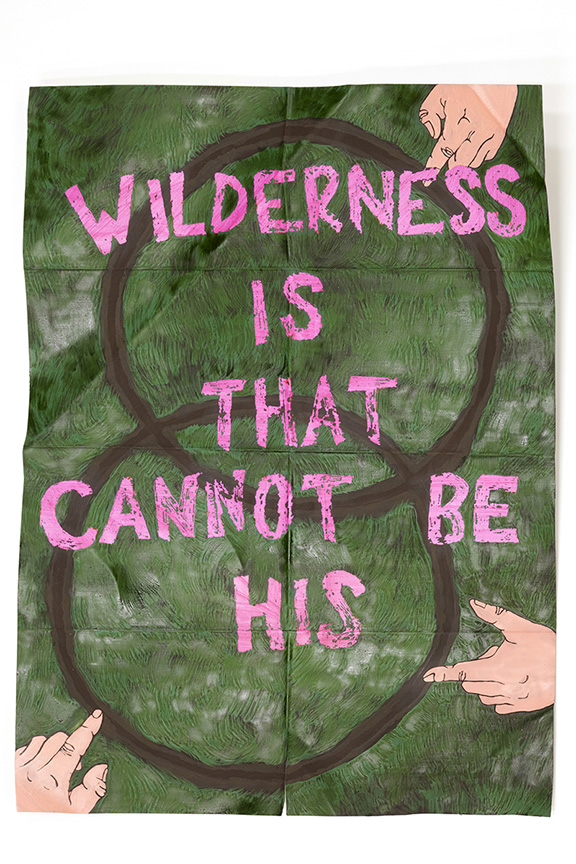

By reclaiming the image of the Halloween crone, the W.I.T.C.H. activists attempted to subvert and disrupt patriarchal constructions of female identity. Marking difficult or dissident women as witches has proved to be a powerful tool of misogyny; from the tale of Adam’s first wife Lilith in Jewish mythology, to the use of the label in modern political discourse in the US and the UK. When a witch is identified in a community, they must traditionally be cast out in order to preserve social norms. The W.I.T.C.H. activists subvert this narrative: their collective self-identification defines the terms of an alternative, transgressive sociality.

W.I.T.C.H encouraged women to identify shared experiences, acknowledge their collective repression and speak out against oppressive forces

Using theatrical costumes, choreographed movement, songs and poems, these feminist covens employed a range of creative practices to heighten the visibility of their actions in public space. Like many radical practices before and since, W.I.T.C.H. refuses categorisation that draws sharp distinctions between theory and practice or art and activism. In contrast, the W.I.T.C.H. actions offer a dynamic model of practice that confounds expectations by switching between different registers of humour, anger, play and politics. This diversity of tone and approach is illustrated by the various titles recorded for the W.I.T.C.H. groups, which include Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, Women’s Inspired To Commit Herstory and Women Interested in Toppling Consumer Holidays. The tangle of narratives represented by these different names provides the starting point for my own work inspired by W.I.T.C.H., which imagines alternative histories for the group in the context of a post-revolutionary future world.

Witches, witchcraft and magic have been increasingly mobilised in contemporary art and activism, as explored in recent articles by London-based writer Izabella Scott and LA-based magical practitioner Amanda Yates Garcia. The resurrection of W.I.T.C.H. by the Chicago Coven in 2015, for example, draws on the aesthetic and attitude of their predecessors. This contemporary coven has led a ritual public procession for abortion rights, hexed property profiteers and cast protective spells against rent increases in the city. While the flashpoints for protest and the public sites of action may have changed since 1969, the desire for collectivity and transformation that characterised W.I.T.C.H.’s early iterations can also be seen to resonate in activist practices such as WHEREISANAMENDIETA, Sisters Uncut and Liberate Tate.

The forthcoming event Witchy Methodologies will consider how the figure of the witch echoes in contemporary queer and feminist practices. Georgia Horgan’s performative lectures trace transhistorical narratives of witches in relation to capitalism, labour and sexuality. Through both poetry and prose, Holly Pester’s writing explores the fictions and realities conjured by language. The collaborative work of Candice Lin & Patrick Staff evokes the witch’s powers to transform the body with herbs and vapours. The ritual performances of Linda Stupart and Travis Alabanza engage with questions of vulnerability, collectivity and protection.

Taking the phrase coined by Holly Pester (in a text written in response to my work) as a starting point, this event will explore the idea of the witch as a producer of alternative knowledge. Acting against the dictates of religious, economic and heteronormative institutions, the witch threatens dominant systems and social conventions. Their unnatural status is represented in defining imagery from the early modern period, which depicts gruesome wizened figures gathered in circles to raise the dead, or flying backwards against the wind.

W.I.T.C.H. emphasized the empowerment of women through collective action

In different ways, the practices represented in Witchy Methodologies assert the body as a site of power and production that is both the subject of, and subject to, trauma and transformations. Like any identity, the witch is always a speculative construction. Historically produced and proliferated through rumour, insinuation and accusation by dominant social forces, the witch is reclaimed in queer feminist practices as a powerful figure of ‘disidentification’ (José Esteban Muñoz, 1999) from the patriarchal construction of woman. What it means to be identified as or to identify with the witch is historically and culturally specific. While the witch hunt produces stigmatised individuals, whose ritual destruction reasserts the homogenous collectivity of the dominant group, Witchy Methodologies will celebrate diverse and subversive collective identifications with the figure of the witch.

Welcome Into The Coven of Heretics! ■

Witchy Methodologies takes place on 13 January. Anna Bunting-Branch's work will be on display as part of Bloomberg New Contemporaries until 22 January.

This article is posted in: Articles, Events

Tagged with: bloomberg new contemporaries, Witch, Feminism, Women in Art, Consciousness-raising, politics, Feminist Activism, Feminist Collaborations