Self-Publishing is Political: An Interview with Dan Mitchell and Sara MacKillop

Ahead of the inaugural ASP fair this year, bringing together over 50 artist self-publishers, ICA Curator Matt Williams caught up with ASP organisers Dan Mitchell and Sara MacKillop to hear about their vision for the fair, how it came into existence and why artists' self-publishing is political.

Matt Williams: Why ASP and why now?

Sara MacKillop: I was first attracted to self-publishing because I had a particular project for which the best format was a publication or a book. I then became interested in the ways you can disseminate work beyond the particular institutional and commercial structure that is the art world. Dan and I both felt that there was a sense of directness in self-publishing that was becoming complicated.

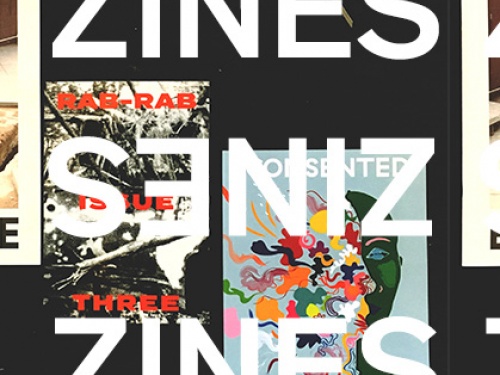

The appeal of it—of just making something, selling it and it being distributed for a small amount of money—was somehow getting lost in a more corporate situation where book fairs were being put on as ventures and money-making schemes rather than just for directly distributing things. There is also a particular interest in self-publishing at the moment because of the easiness of printer demand and graphic design programmes; it’s good to reassess the different possibilities for publishing and what it can be.

How does ASP differ from other independent and self-publishing book fairs such as Publish and Be Damned or Three Letter Words?

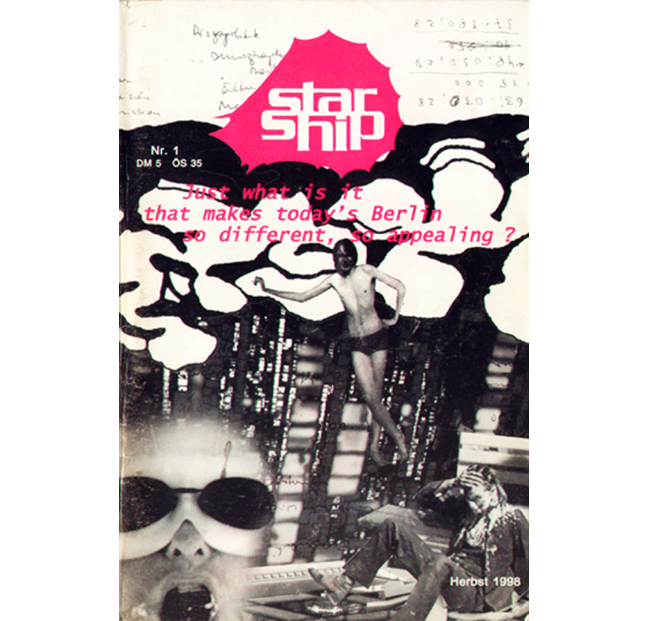

Dan Mitchell: Publish and Be Damned started with quite a lot of intensity in 2004 and it became quite obvious from the first fair that it was something exciting and good. Before, there were small zine fairs or boot fairs, but there wasn’t a dedicated self-publishing fair. It took off and lasted ten years. One of the things that I liked most about it was that it was a point where people could come together and share something relatively humble with themselves and an audience: self-publishing. Nothing cost that much money, and so there never seemed to be a way in for a neoliberal agenda of growth or corporatisation or exploitation. It could exist as a kind of ‘punk’ ethic.

After it came to an end, we felt we could put something together which would riff off that spirit. Over the ten years that Publish and Be Damned existed the world changed: things were being described as ‘self-publishing’ that really weren’t. There was a huge injection of money that had changed it into something more alienating and unattainable. We felt that that didn’t have to be the case - we didn’t have to let self-publishing become yet another victim of regeneration or gentrification or neo-feudalism. We could put something together for not too much money, have some fun and give these publications the opportunity to get out there.

And what were the selection criteria?

DM: It was very simple. You had to be an artist, it had to be self-published and it had to be for sale. Over the last few years I’ve seen a lot of people who hijack being an artist, when actually they’re a fashion designer or an architect. You can talk about the free flow of these things if you like. However, I’m a bit old school in that respect: artists are artists, and artists make art. So, you had to be an artist. It also had to be for sale as that cancels out all of the free shit - because free equals shit, right? They were very simple criteria, designed to try to enshrine something that we personally have found very difficult to define: what is self-publishing?

SM: Once we started to contact people, there was such a lot of positive feedback about it being focused on artists’ self-publishing and about the criteria that it felt as though this really was something that not only Dan and I were thinking about.

DM: We felt that there was a space for something that was much more hermetically sealed. The best versions of this tend to recognise that self-publishing is an art form in itself. It’s a way of disseminating art in a democratic and cheap way because, at the end of the day, as an artist the struggle you are always going to have is that you are making luxury goods for rich people which is very problematic. If you start to follow the money, your work changes in a way that, as we have seen historically, is not always good.

The thing about self-publishing is that, because it doesn’t cost very much to do, people can own a piece of art for five or ten pounds. That’s a really valuable and remarkable thing, especially given the kind of climate we’re in now with the elite taking power and inequality becoming more evident than it’s ever been before. So, there is also a political mandate to this which is trying to take a stand or draw a line in the sand and say: we don’t have to knock down every pub and turn it into a yuppie drone, we don’t have to push the poor people out of the centre, we don’t have to buy into this neo-feudal, alienating experience. We can house poor people in central London, we don’t have to have homeless people. We can have self-publishing!

As artists working in self-publishing I know that you both wanted to be rigorous when selecting the participants but you also invited open submissions. How did you determine the balance between established self-publishers and the open submissions?

DM: There were a few obvious names - people who we knew had been around for a while and who we were pretty sure would be into this. And then we put our toe in the water and invited a few more. The response we got was really excellent, so we had seven or eight key players and we started to build a list around them. We didn’t want to have too much of the same thing and we wanted to have a diverse or even spread of self-publishing. But, we also had to recognise that being in London and having done this for quite a while, our vision was, to some extent, obscured. So, we opened up an open submission to see if we could find out what we didn’t know. And we got 50-something admissions ranging from very obscure, fairly crazy things to others that were more accomplished. So it began to build its own gravity, pulling in people, and slots began to open up. It almost did itself after a while. When we had the skeleton, the flesh kind of started to apply itself.

SM: It also opened up from these communities we’ve been working with for a while. We asked a lot of other people who have been involved in it their advice or who they would suggest, to make sure that we had a good cross-section of things that were going on.

Finally, what are your ambitions for the inaugural ASP?

DM: I would like our friends and new friends, the publishers, the artists to walk away satisfied, if not delighted, so that’s about footfall. There’s a sort of John Lewis, Sainsbury’s kind of attitude to this: let’s get as many people through the door as possible.

Or Waitrose?

DM: It’s more Waitrose than Sainsbury’s. Anyway, the success of the fair for me can really be measured by how successful the publishers think it is, how much they are selling, how many people are turning up, whether it is good for them basically.

SM: And if they have a laugh! ■

ASP Fair takes place at the ICA on 12 September 2015.

This article is posted in: Blog, Interviews

Tagged with: ASP Fair, Artists' Self-Publishing, Dan Mitchell, Sara MacKillop, Matt Williams, ICA Bookshop, Publishing, events, Fairs