The ICA at 70: An Interview with Gregor Muir

To mark the beginning of a new series of posts celebrating the ICA's 70th anniversary, Maya Caspari spoke to ICA Executive Director Gregor Muir about his memories, what is unique about the ICA and his hopes for its future. This is an edited transcript of the conversation.

What was your first encounter with the ICA?

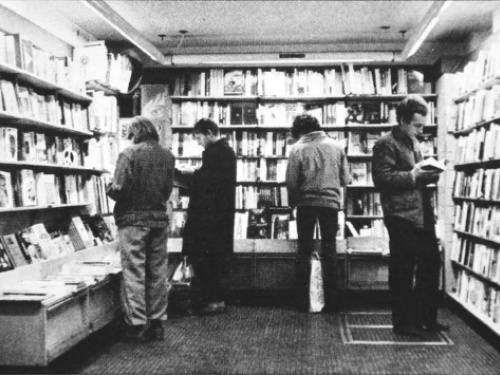

My first encounter with the ICA was probably a lot like that of many others. I first came as an art student in the mid-1980s when it would’ve been impossible not to come here - it was where you met all the other art students from other art colleges in London. It felt like you needed to be here as often as possible.

Since you’ve been ICA Executive Director, what have been the highlights for you? Has anything surprised you?

It was very odd watching Nick Clegg resign in the Nash Room – a last-minute private hire while I was abroad. It had obviously happened so quickly that word had yet to reach me. I’m often fascinated by the strange interactions that exist owing to our being in the political centre and what might be going on elsewhere in the building!

More broadly, the ICA has never ceased to surprise me in some shape or form. Sometimes I’m surprised at nights when I look around and see such a mix of people who are eager to know more about the creative world in London. People sometimes feel that art students don’t come here in the same way that they did when they were younger. But the fact of the matter is that they do!

"The ICA is fluid. It moves and bends and flexes with art."

It's not just a place for art students. People who really enjoy art and culture come to the ICA, partly because they have a place in the bar to talk about it afterwards. That’s what I like about it. There’s still a real social whirl about the place. It doesn’t just go away because you might - it’s actually going on all the time. That’s because of the programme, which remains as interesting as it always has been – it’s still pioneering.

From its early days, the ICA has been committed to exploring arts across disciplines and showing emerging artists. Now that we are seeing what was once considered avant-garde or radical moving into the mainstream and being adopted by other galleries, how does the ICA maintain its radical identity? What do you see as being radical today?

In a sense the ICA has been joined by numerous contemporary art spaces. You could argue that it now has a challenge to distinguish itself in the world. Yet, at the same time, I can’t think of many galleries that have a cinema attached, a truly ambitious talks programme, and also run events such as performance, dance and live music. It’s a very multi-faceted place. One has to acknowledge that. I don’t really see an equivalent to the ICA anywhere. It also has this incredible legacy which makes it really unique. The ICA’s heritage is key to its activities in the present.

"The ICA’s heritage is key to its activities in the present."

The ICA remains a pretty good judge of what’s culturally important. It is, as Jasia Reichhardt once said, a weathervane for the artistic temperaments that sweep through the international art world. It's always going to remain pioneering because it’s not fixed - it’s flexible and adaptive. It responds to artistic and cultural urgency across many disciplines. It’s able to take not just a long view but a 360° view of how contemporary art and culture are presently being played out. People might say they don’t know what one thing it is, but it is fluid. It moves and bends and flexes with art, which is what a really valuable, responsive organisation should do.

It’s interesting that the organisation is simultaneously engaged in exploring its legacy, while remaining responsive to the contemporary. What do you see as being the key moments in its history?

It has always been driven by its programme and by the activities that people on the ground feel strongly about. It’s quite an unusual creature in that it’s really a narrative-led organisation. It's a living organism.

"The ICA's fundamental interest has always been in following the artist and what the artist wants to look at."

A highlight one can immediately point out is its foundation in 1946 as the first organisation to address the arts in London at an international level and to resist the more conservative leanings of the day. Thereafter comes the Independent Group, Pop, Brutalist architecture and this sense of an organisation that is prepared to look at design as well as contemporary art. It was prepared to look at artists working in performance, in craft, architecture, photography and in all the more conventional media of that period, including painting and sculpture. Its fundamental interest has always been in following the artist and what the artist wants to explore.

In the 1960s, it would have been a beacon of light to the international art movement. A number of artists would have passed through who were connected to the counterculture of the day and to the beginnings of a more political and a more activistic leaning in the artistic community.

By the 1970s, it was one of the few organisations in Europe that could so clearly grasp things like performance, and really openly embrace artists working across Europe. Thereafter, in the 1980s you see an incredible movement through music. It became well-known as a punk band venue, and then a post-punk venue, presenting bands like Throbbing Gristle and The Smiths.

"We are able to bring things into the centre as they are being pushed away from it."

It then became one of the few venues that tracked Pop into mass culture. Those artists who emerged in the late 1980s begin to make their presence known in the 1990s when the ICA captures the Young British Artists and the beginnings of contemporary art as we know it today.

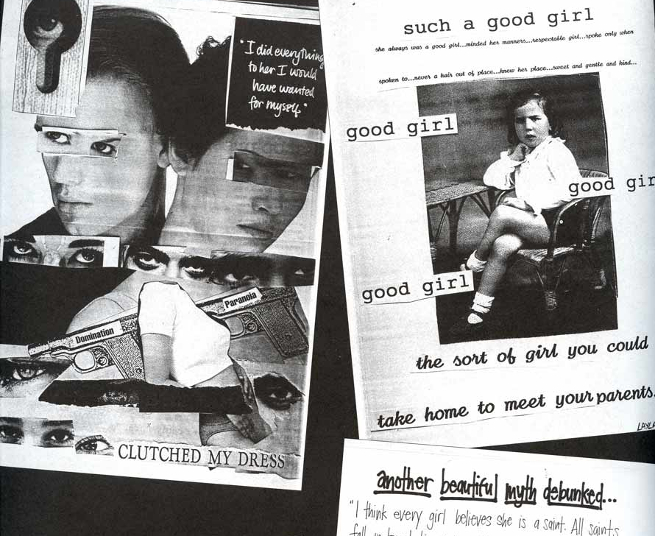

Wonderful group shows like Belladonna and Bad Girls, showing a number of women artists, also marked the rise of the curator and the contemporary curated show. Exhibitions such as The Institute of Cultural Anxiety, curated by Jeremy Millar, became landmark shows. Going into the 2000s, you had Jens Hoffman curating Tino Sehgal for a show each year over three years, alongside more legacy-driven projects such as the exhibition Poor. Old. Tired. Horse with its focus on concrete poetry. There’s always been a sense of the organisation feeling its way through time. It doesn’t just churn things out - it’s conscious as an organisation, sentient.

How is the ICA responding to the present?

The ICA’s role is to track popular culture—and to re-examine our understanding of mass audiences especially—as we move into the digital age. It has really been looking closely at this, sometimes perhaps in quite far-fetched ways! The Betty Woodman show suggested a return to craft while at the same time appreciating that many young artists are emerging into a world driven by technologies such as the internet, social media and so on - so much so that making, the handmade and craft become serious alternatives.

For me it’s vital that our audiences are very mixed. It’s important that we engage young artists, as well as older generations. I’ve noticed more senior people arrive at the ICA and sometimes find that they’ve been members for decades and that they are themselves important artists, who I just hadn’t recognised at first. At 90, Gustav Metzger has probably come to the ICA about five times this year already!

There has recently been much discussion about the damaging impact of gentrification on the arts and artists in London. How do you see the ICA's role, and responsibility, as a public arts institution?

We are able to show the work of artists to a wide, international audience due to the fact that we are in the middle of London. Our central location presents itself uniquely in terms of the kind of audience we can bring to the kind of artists and filmmakers and creatives that we show. I think that’s really vital - that we are able to bring things into the centre as they are inextricably being pushed away.

"I hope people see the ICA as a flag firmly planted in the centre of London for artists - we are always going to be here for them."

Artists will have to adapt as space is removed from them - as it is from most of the British public. But I hope people see the ICA as a flag firmly planted in the centre of London for artists; we are always going to be here for them. It shouldn’t be the case that everything in the centre that is not a commercial gallery or major museum is pushed out.

What do you hope for the ICA's 70 years?

I think the ICA deserves a great future. It has a remit which allows its programme to adapt according to artists’ needs and interests and I think that should remain the case always. As long as it does that, I think it will always be a receptacle for the most interesting, challenging and pioneering art of the day. That’s the key thing – that it remains loyal to its sense of troublemaking, of being critical, of not just joining in with an increasingly commercial art world but being able to call the shots. ■

Learn more about the ICA's 70th Anniversary

To help celebrate our anniversary, we have put out a call to members for any further stories or archive material from the ICA’s illustrious past, in order to record the ICA’s incredible history. Any material should be shared with archives@ica.org.uk.

This article is posted in: Blog, Events, Exhibitions, Film, Interviews, Members News, News

Tagged with: Gregor Muir, ICA 70, ICA Archive, Archive, ICA History, Exhibitions, events, Cinema, Music, ICA Executive Director, Future of the ICA, Maya Caspari, interview, interviews, From the Archive