Home Movies: An Extract from Juliet Jacques' Trans

Ahead of our Culture Now with Juliet Jacques on 25 September, we are pleased to present an extract from her book Trans (Verso, 2015), a moving memoir and insightful examination of transgender politics. Juliet Jacques is a freelance writer, best known for the Guardian’s A Transgender Journey - the first time the gender reassignment process had been serialised for a major British publication.

I hadn’t known about it at the time, but in 1988, when I was seven, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government passed Section 28, which banned the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools. This law virtually silenced any positive discussion of sexuality or gender in British classrooms, and meant we only had one hour on sexual diversity at Oakwood, delivered in Religious Education, weeks before our final exams.

Our teacher announced that we were going to watch a video. ‘It’s about two boys who … well, I think it’s just a phase, but … well … they’re … umm … they’re homosexual.’ He rushed the crucial word under his breath.

Bill, who’d been made to sit at the front, raised his hand.

‘Sir …’

‘Yes?’

‘What’s a homosexual?’

The teacher went red. ‘Watch the film,’ he told us, hoping to avoid any follow-up questions.

In the film, two young male students quiver through a lesson in which they are told that ‘one in ten people is homosexual.’ Another pupil stands and shouts, ‘That means there’s two in here! Is it you?’ He points at the two young men. I rolled my eyes as Richard did the same in our classroom, and laughed wearily as the two boys in the video, probably filmed in the early 1970s, ran away to go camping together.

I’d never dared talk to anyone about my gender identity, or my sexuality. At school, I got told that I sat ‘like a queer’ just for crossing my legs, so I felt that being open about who I was would end badly. There was nothing to help me in Horley Library either, so everything I learned about the subjects came from films and TV programmes – the ones I’d chosen to see by myself.

——

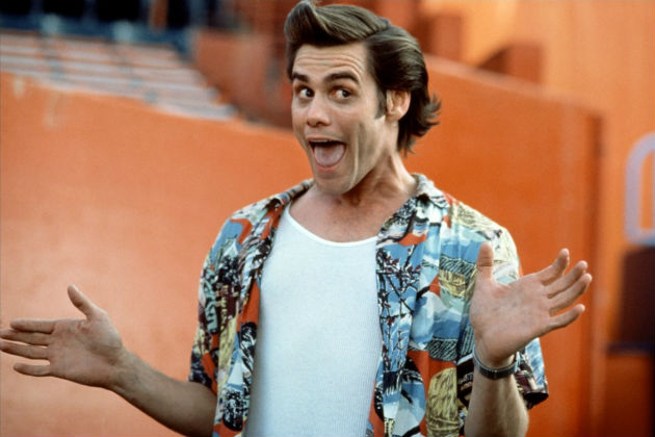

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994) wasn’t something I’d wanted to watch. The main reason I’d rented it from my local video shop was because the boys in my Year 10 History class endlessly quoted it, and I wanted to be able to laugh with them. Mostly, I didn’t care for it: the film’s brand of gross-out humour wasn’t my thing. The comedic climax hit me hard, but not, I suspected, for the same reason as it did everyone else I knew.

Unravelling the mystery at the core of the plot, Ace Ventura (played by Jim Carrey) realises that Lois Einhorn, the Miami Police lieutenant whom he has kissed, is transsexual. She was once known as Ray Finkle, a former American football player whose disappearance has formed part of Ventura’s investigation. ‘That’s it!’ he yells. ‘Einhorn is a man!’ His face fills with disgust. ‘Oh my God! Einhorn is a man!’ He races to the toilet and is sick. Then he squeezes a whole tube of toothpaste and a plunger into his mouth, before burning his clothes and jumping into the shower, crying, ‘No! No!’ Then he leaps into his car and drives off to seek revenge.

Finding Einhorn in a room full of people, Ventura points and screams: ‘She is not Lois Einhorn! She’s a man!’ When Einhorn says he’s lying, he yanks at her hair, hoping to pull off a wig. No luck: it’s real. He rips open her blouse, saying, ‘Would a real woman be missing these?’ She has breasts, so Ventura turns, laughing, and shouts, ‘That kind of surgery can be done over the weekend!’ Nobody stops him: Ventura strips off her trousers and then looks astonished. Where is ‘big old Mr Kanesh’? Dan Marino, the Miami Dolphins’ star quarterback, tips him off. Ventura turns Einhorn around, showing the crowd that the deceptive Einhorn has tucked her male genitalia between her legs, and screams: ‘That’s why Roger Podacter [whom Einhorn has supposedly killed] is dead! He found Captain Winky!’

Every man pukes in unison: clearly, I was meant to puke with them, or at least laugh. I couldn’t, but I still felt sick.

——

Ace Ventura’s cruelty had come as a shock. In response, I looked for films that might be more sympathetic. I tried The Crying Game (1992), directed by Neil Jordan. I already had some idea of its famous ‘twist’ from The Simpsons, when Mayor Quimby told a crowd of voters: ‘The chick in The Crying Game is really a man!’ When they booed, he backtracked: ‘I mean, man that was a good movie!’ So I watched as IRA member Fergus fell in love with Dil (Jaye Davidson), the girlfriend of a hostage held by Fergus’s group and then accidentally killed. Their relationship was handled with admirable sensitivity, the romance growing as Fergus protects her from hostile men in the nightclub where she sings, until he gets her to the bedroom: she drops her knickers, ‘revealing’ her male genitalia.

‘I thought you knew …’ says Dil, as Fergus rushes off to throw up. Apparently, he didn’t, and the idea was that Dil ‘passed’ so well as a woman that viewers didn’t either. I was seeing that the ‘surprise’ was a convention – or cliché. I didn’t realise for years that Fergus soon apologised and carried on dating Dil – seeing her draw that kind of response from him had made me turn off the TV, and look elsewhere for people who I thought might be like me.

Soon, I discovered that transsexual people should not ‘deceive’ anyone about who they were, but shouldn’t be open about it either. I watched a short documentary on Channel 4 called Murder and the Feather Boa (1996) about the killing of La Vanessa, who organised the first gay rights march in Chapias State, Mexico, and then of twenty-nine other transvestites and transsexual women, many of them sex workers.

I saw that for many people around the world, expressing themselves as they wished meant risking death. For once, I felt grateful to have grown up in the suburbs of southeast England – my anxieties paled next to the challenges faced by these women in Latin America, not least at the hands of the police. I also had a far easier life than Brandon Teena, a trans man killed in Humboldt, Nebraska, in 1993, played by Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry (1999). Brandon’s struggles to fit in with the guys in a small American town while keeping his gender secret ended with him being raped – for which he was blamed – and then murdered. I only saw the film after I came out as transsexual, but I could well remember the fear that came with those youthful conversations about what I enjoyed doing or who I fancied, as I sat terrified that giving the wrong answer would lead to bullying, exclusion and violence.

But the tragedies were collective as well as individual. In secret I watched documentaries about drag queens, transvestites and transsexual people who’d survived the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s talking about how it had changed queer subculture forever. In one documentary a character sat in a London cab with tears in her eyes as she spoke about her friends ‘dropping like flies’ and how she missed the ‘family’ she’d fought so hard to find. I liked the sound of the community she described, feeling sad that I’d never know such comradeship, but I also felt relieved, as I struggled to comprehend the scale of the crisis, that the worst of it was over, at least in the West.

A world had changed, perhaps been lost – something I started to understand as I watched Stonewall (1995), directed by Nigel Finch. The film opened with someone putting on lipstick, and then a tracking shot along a bar where there had been a fight. It cut to archival footage of Richard Nixon and various moments in the 1960s civil rights movements; the people interviewed recalled that ‘every other group had made their point’ and that it had been time for the ‘faggots’ to make theirs. But the heroes weren’t the ultra-cautious, white ‘homosexual rights’ activists who insisted that men wear suits and women wear dresses to their peaceful protests, but the African American ‘drag queens’ of colour who sang and danced in New York’s dimly lit Stonewall Inn.

Stonewall didn’t feature Sylvia Rivera or Marsha P. Johnson, who were at the riots and then set up the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries to advocate for homeless queens and queer youths; it was only years later that I found out how central they had been to the struggle of July 1969. This story belonged to Miranda, originally from Puerto Rico. She was at the bar, explaining to Matty Dean, a young gay man who had just arrived from the southern states, that he had to keep his identity secret. ‘We’re all Smiths in this place,’ the queens told him – just before the police broke in and demanded ‘ID’, targeting anyone not ‘wearing at least three items of clothing appropriate to their gender as ascribed by nature’. The police were smug, arrogant and cruel. During the first raid, a cop walked up to Miranda, sarcastically saying, ‘So classy and dainty it is’ before taking off her glasses and ordering her to the washroom. They dunked her face in dirty water to ruin her makeup, laughed at her and called her a ‘sissy’; when she put her lipstick back on and Matty Dean stood up for her, they were both arrested, along with the other queens.

I loved how Miranda revelled in a position between male and female – she preferred to be called ‘she’ and went to the army headquarters in women’s clothes after being ordered to enlist for the Vietnam War. The recruiting sergeant called her ‘lady’ at first, and she replied: ‘I ain’t no lady, that’s why I walk the middle of the room.’ They asked if she was ‘some kind of invert’ and stamped ‘sexual deviant’ on her application, excusing her from service. I felt so inspired by Miranda and the queens who joined arms with her outside the Inn: they refused to keep quiet and blend in, knowing that they could only bring about change by standing up for themselves, together, and fighting discrimination with radical action. ■

Juliet Jacques is in conversation with Sophie Mayer on 25 September, as part of our Culture Now talks series.

Read Sophie Mayer's blog post on films that have re-envisioned queer and gender-nonconforming people into history.

Trans is published by Verso. It is available from the ICA Bookshop.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film, Store

Tagged with: Juliet Jacques, Trans, Culture Now, events, Blog, Film, books, ICA Bookshop