On Cinema's Nerve Ends: The Essay Film

Ahead of the opening of this year's Essay Film Festival, deputy editor of Sight & Sound Kieron Corless reflects on the indeterminate and uniquely challenging nature of the essay film.

The slippery term ‘essay film’ was first coined by the filmmaker Hans Richter in the 1940s, but it wasn’t until 1958 that one essay film in particular, Chris Marker’s Letter from Siberia, was designated and theorised as such by the great French critic André Bazin. As the form developed and exploded through the political ferment of the 1960s and onwards, in the hands of such major figures as Marker himself, Jean-Luc Godard, Harun Farocki, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Agnès Varda, Fernando Solanas, Patricio Guzmán, Chantal Akerman, and Straub-Huillet, to name but a few, the question of what constituted an essay film became more pressing.

"An essay film will often seek to unfix or disrupt categorisation."

At first glance, it could be taken for a species of documentary; a personal cinema of ideas that foregrounds the director’s subjectivity through first-person narration, pursuing a certain line of argument or set of associations. That’s a workable definition, but to what extent is that speaking ‘I’ a performance, and therefore a distancing or fictionalising device not to be taken completely at face value? And how to account for those films that eschew voiceover altogether, but still manage to convey a distinctively personal take on the world or a particular subject, such as Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera, or many of Harun Farocki’s later films?

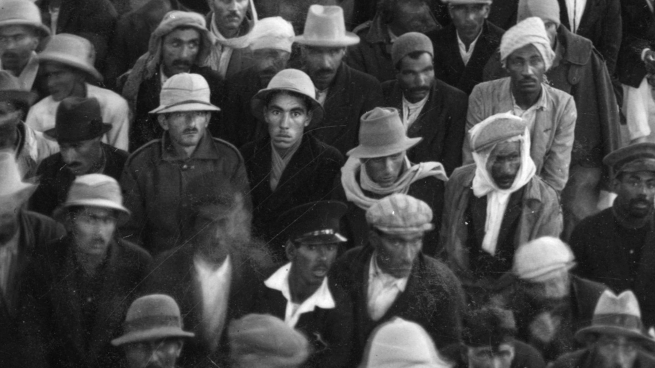

And what about the actual image itself? Many essay films use archival images and found footage as their primary materials - the Russian director and editor Esfir Shub, featured at last year’s Essay Film Festival, would be a case in point; not just for illustrative purposes, as is often the case in journalistic documentaries, but as the subject of an ontological enquiry into their status and politics, into the vagaries of both personal and institutional memory. What does the archival image exclude and occlude as well as reveal? That’s a question that haunts essay filmmakers such as John Akomfrah and, in the current Essay Film Festival, Miranda Pennell.

"What does the archival image exclude and occlude as well as reveal?"

Nowadays then, most commentators agree that the essay film is neither documentary nor fiction but sits somewhere on its own, evincing characteristics of both through its staging of an encounter between a ‘self’, filmed and/or archive images, and the world at large. Could we label it a genre? Probably not, since an essay film will often seek to unfix or disrupt categorisation, can be actively inimical to such acts of closure; open-endedness and allusiveness are its watchwords. Think too of the sheer variety of this notoriously hybrid form – notebooks, sketches, diaries, letters, all grist to its mill.

No wonder elusiveness and instability seem ingrained in the essay film’s DNA; more than any other filmic mode or form, it will seek to invent itself in the process of its own becoming, twist into tantalising new shapes, wrestle with the apprehension of its inevitable limitations. In other words – cinema at its most risk-taking, engaged and liberated, operating right on the medium’s nerve ends; probing, questioning, subverting, laying bare its own thought-processes. Hardly surprising that so many of the world’s greatest directors, and many others besides, have been unable to resist its lure. ■

The Essay Film Festival runs 18-24 March at the ICA. See the full programme on the Essay Film Festival website.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film, News

Tagged with: Essay Film, Kireron Corless, Man with a Movie Camera, Experimental Film, Jean-Luc Godard, Chantal Akerman, Miranda Pennell, Archive, Birkbeck, Film, events, Films, Film Festival