Archive Fever

Why the ICA archive matters

ICA Archivist Dan Heather discusses why the ICA’s archive matters, and how it can be reconciled with an outward-looking commitment to the contemporary.

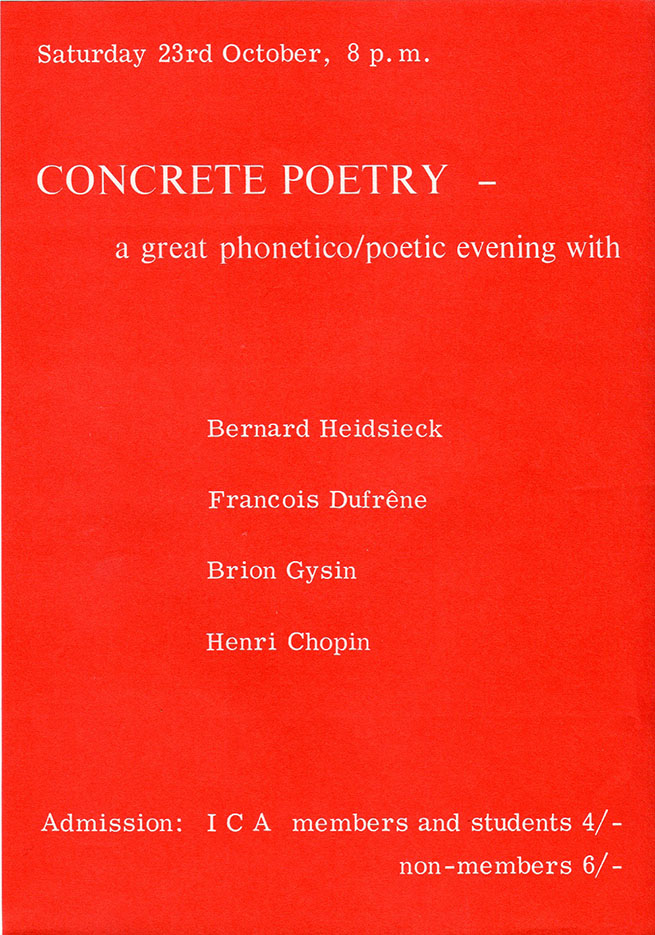

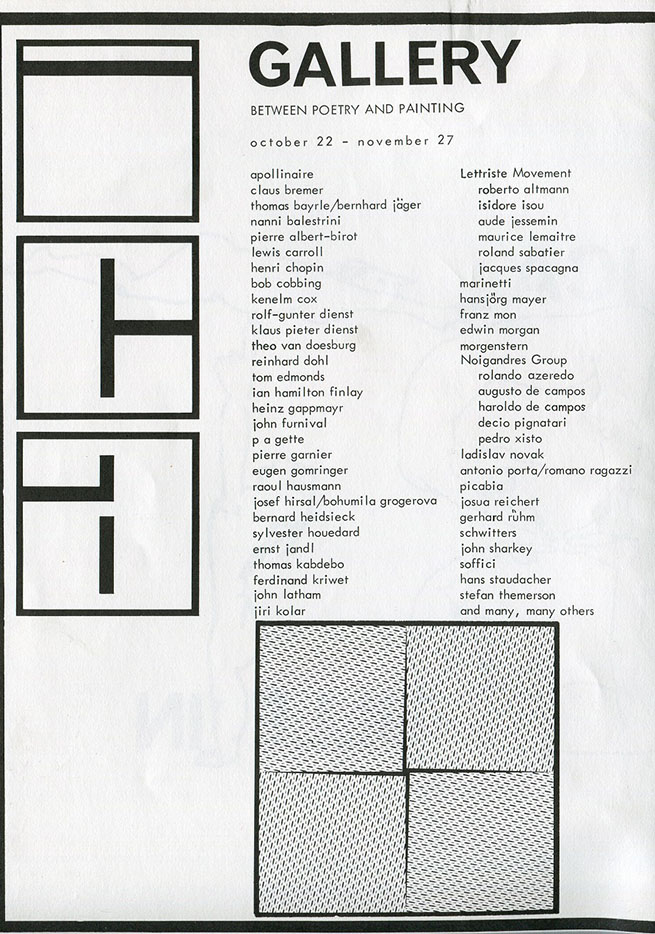

The ICA has never had a permanent collection of artworks, but over the last 70 years it has nonethless accumulated a legacy of records documenting the arts. This record forms the ICA’s institutional archive and includes installation photographs, exhibition files, slides, Betacam cassettes and posters, and has only become a focus of the ICA’s own attention in more recent years. In 1995 the decision was made to transfer its records up to 1987 to the Tate Archive of British Art, in order to guarantee their long-term preservation and access: I am currently working on a project to review the more recent material that has thus far remained with the ICA. This project provides an opportunity for us to assess what it means for a contemporary organisation to engage with its archive.

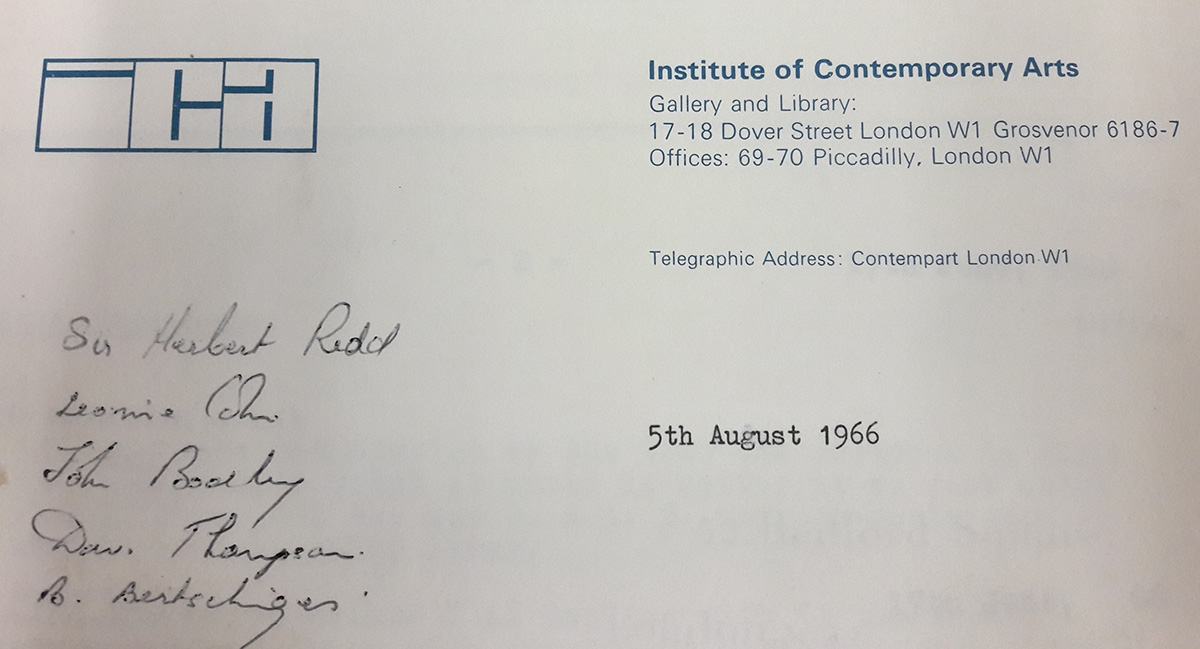

The ICA’s resistance toward the museological turn was present as early as the late 1940s in its decision to adopt the name The Institute of Contemporary Arts. Herbert Read, one of the ICA’s founding figures, had originally proposed a Museum of Modern Art for London, mimicking the model (and perhaps the nomenclature) established by MoMA in New York. However this name was ultimately rejected, with Read stating in 1948 on the occasion of the opening of the ICA exhibition Forty Years of Modern Art:

Such is our ideal – not another museum, another bleak exhibition gallery, another classical building in which insulated and classified specimens of culture are displayed for instruction […]

As an archivist, invested in classification and taxonomy, I can read Read’s statement as a refutation of the desire for structure and order that informs my professional practice. The reality—as is often the case with the ICA—is more complex. While avowing a collecting culture on one level, the ICA was also intimately involved with the Independent Group in its early years, a group whose practice was informed, as Hal Foster has noted in An Archival Impulse, by a "pinboard aesthetic" where "appropriated images and serial formats became common idioms". This archival art practice within the Independent Group itself throws a different light on the relationship between the notion of the archive and the ICA.

An indebtedness to a collecting culture is also present in the ICA’s library, an important element of the ICA when it was based in its former location at Dover Street. A 1950 note from the ICA archive articulates the need for a "library and information centre; this would incorporate facilities for the storage and reading of books and magazines". Early architectural drawings by the firm Fry, Drew and Partners for the ICA’s new home on the Mall (where the Institute moved in 1968) also demonstrate an ultimately unrealised intention to establish a similar library in their new home.

The archival turn in curation has meant an increasing presence of archive material in exhibitions in recent years, and a genuine risk that Derrida’s "archive fever" gives way to a sense of archive fatigue. However, the strength of the ICA’s own archive lies in its power not only as a repository for documents but, to quote Simone Osthoff in Performing the Archive, as "a dynamic and generative production tool". The notion of the archive as a point of departure as opposed to a point of termination for artists, curators, academics and activists seems particularly timely when, as Kate Eichhorn’s writes in The Archival Turn in Feminism, the archive functions "not only as a conceptual space in which to rethink time, history and progress against the grain of dominant ideologies, but also as an apparatus through which to continue making and legitimizing forms of knowledge and cultural production that neoliberal restructuring otherwise renders untenable".

The notion of the archive as a point of departure as opposed to a point of termination for artists, curators, academics and activists seems particularly timely

Interest in the ICA’s history has increased, as a wide range of researchers seek to explore not only the ICA’s conviction toward championing the contemporary for 70 years, but also its absences, mistakes and near misses. This critical and probing relationship with the organisation’s past facilitated by the archive is a key asset in ensuring it continues, in the words of former ICA Director Michael Kustow, to function as "a place which seeks new ceremonies for our times, and yet does not seek an utter break from the past". ■

For those interested in the ICA’s history, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1946-1968 is available in the ICA Bookshop

This article is posted in: Articles

Tagged with: Heritage, history, ICA Archive, ICA 70, Herbert Read

%2c_ICA%2c_1974._Photography_%c2%a9_Gerald_Incandela/index.jpg?itok=nev9eqOI)