Smoulder and Curl

An interview with Annette Kennerley

London filmmaker Annette Kennerley's films explore themes of childhood, motherhood, love, loss and sexuality. In this two-part interview, she discusses her practice and work with Club des Femmes co-founder Selina Robertson ahead of her screening and Q&A event as part of the London Short Film Festival. Part two of this interview can be found on the Club des Femmes' website.

Your films about London’s 90s dyke scene document a rich treasure trove of lesbian history, sexuality, memories, clubs, bars and encounters. I’m particularly thinking of After the Break and Sex, Lies, Religion – what were your intentions making that work?

I certainly never started out to intentionally record or document an era, but watching them now makes me realise just how much these films captured of that particular time and scene, places and lifestyles. Perhaps the way we lived as lesbians has changed – I don’t know if that’s true. Clubs and bars are referenced that no longer exist but they were where we lived out our lives: Sex, Lies, Religion emerged from a random encounter at the short-lived Clit Club in Vauxhall. There were discussion groups and workshops to explore our views about lesbian sexuality and sexual politics – there were ideas about how we should behave and those who didn’t want to behave at all.

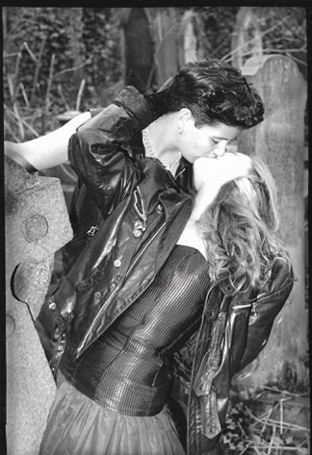

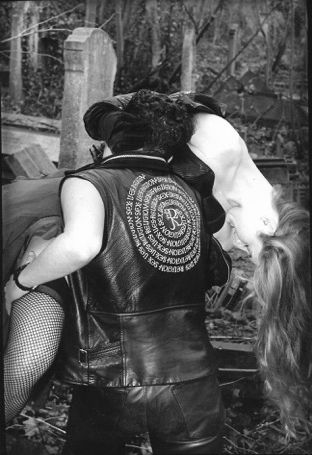

There was a desire amongst many artists at that time to break down taboos and challenge representations of lesbians and sexuality, to reveal the darker sides – often unspoken and controversial even within the lesbian community. We had clubs for women that were more like the gay men’s spaces, and maybe we sought to dip our DM toe caps into that male domain. Our relationships were unconventional, open, multiple, fluid, often anonymous and spontaneous. It was like we lived this secret life in a secret world – and of course this made it all the more exciting, too. It felt like an era of exploration, of re-working and re-defining our own identities and experimenting with ways of living our lives and being in relationships.

There was a desire amongst many artists at that time to break down taboos and challenge representations of lesbians and sexuality.

But there was so much I wanted to portray that wasn’t shown in the mainstream and I still don’t know if it is really. I used my work to examine and explore some of the issues we were working through and the ways we lived and loved. These films are about chance encounters, non-monogamy, sexual dynamics, power, love, lust and loss. They capture a moment, like a snapshot: unscripted, spontaneous and unpredictable. The words came from my personal writings. And yet, while these films remain as intimate filmic diaries for me of formative years of my life, of experiences and emotions that are deeply personal, I also hope they are universal in that they resonate and touch most people who see them.

I used my work to examine and explore some of the issues we were working through and the ways we lived and loved.

You set up London’s first International Transgender Film & Video Festival (1997-2000) with Zachary I. Nataf. Why did you decide to set up the festival, did you receive funding, can you tell us about your programming remit and what was the response from the LGBTQ community?

Zach was a friend of mine and a passionate trans activist. He was determined to set up a festival to provide a platform for trans people to portray their lives and to represent themselves. His enthusiasm inspired me to work with him to launch the festival with very little funding but an amazing team of volunteers – we were all volunteers. We had some small amounts of funding from the BFI, National Lottery, Arts Council, London Arts Board, London Film & Video Development Agency, Channel 4, Cinenova and a number of transgender organisations but never enough to pay any of the many people (including ourselves) who worked so hard to make it all happen. Nevertheless, we were extremely ambitious: we staged several days of films, performance, art, archives, awards, discussion panels and parties with international guests and we ran it for three years at The Lux in Hoxton Square.

Our aim was to deliver a broad spectrum of trans-global and cross-cultural representation under an all-encompassing trans umbrella – to do for transgender audiences what lesbian and gay film festivals had done for gay people. We hoped we achieved some of that aim. The festival brought together packed audiences, mainly from the trans and gay communities; it gave people a voice and a platform and it opened up an arena for a huge amount of essential and groundbreaking debate. Not everyone in the gay and lesbian community embraced or accepted trans people in those days, which is why events like this were so important.

For you personally, returning back to the ICA might bring back certain memories from January 1994? Can you tell us more?

Sex, Lies, Religion screened at numerous film festivals worldwide for several years. Its first-ever outing was very grassroots—it was first shown as a work-in-progress at one of Gay Sweatshop’s One Night Stand events in November 1992—and the unedited rushes were projected onto a makeshift screen in a club and the script was spoken live by my friend Jo, with me squeezing her leg to prompt her. It also screened at the ICA in January 1994 in competition for the infamous annual Dick Award for "the most provocative, innovative and subversive short film made in 1993". A film called Ding Dong won the award but we girls found it amusing and subversive that the film had even been included in the competition. And we went on upstairs to party with the boys—including Bernardo Bertolucci—and to harangue the organisers to start up a new award named after the women’s equivalent to the Dick Award. It still hasn’t been done… ■

Part two of this interview can be found on Club des Femmes' website.

London Short Film Festival and Club Des Femmes present Five Films by Annette Kennerley + Q&A at the ICA on January 8.

This article is posted in: Articles, Film, Interviews

Tagged with: Cinema, Artists' Moving Image, Club des Femmes, Annette Kennerley, Feminist Film, Queer Cinema, LGBTQ

/index.jpg)

%20WEB/index.jpg)

/index.jpg)