Countercultural Designs: The House of Beauty and Culture

House of Beauty and Culture promotional image by Cindy Palmano for Blitz Magazine, 1988. © Cindy Palmano

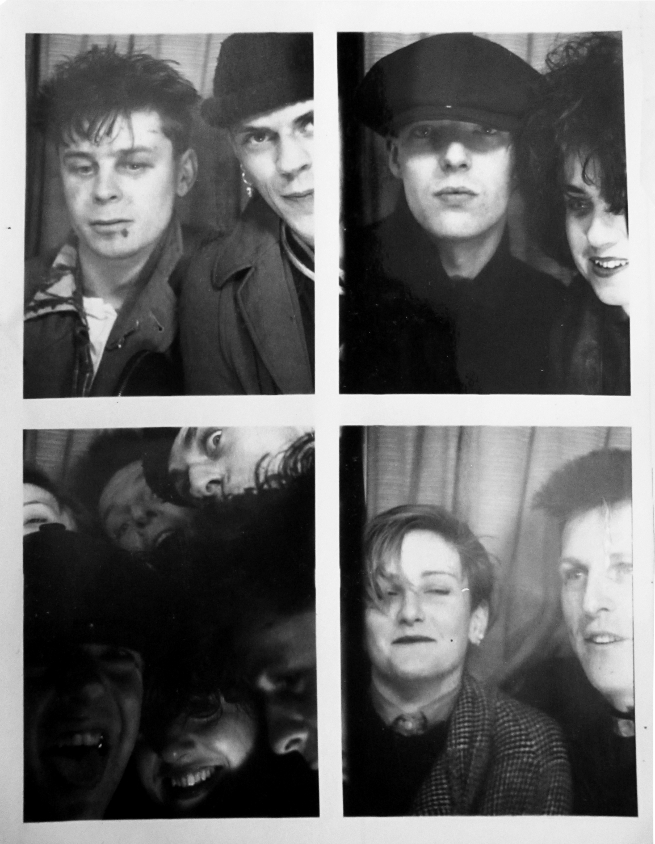

In the 1980s, boutique, design studio and crafts collective The House of Beauty and Culture (HOBAC) changed the cultural landscape. Experimenting with deconstruction and championing androgynous style, the collective expressed and embodied the experience of a generation of avant-garde Londoners reacting to a world of Thatcherism, mass production and the AIDS crisis. A key member was accessories designer, art director and fashion stylist Judy Blame, whose exhibition Never Again runs here until 4 September.

This is an extract from new book The House of Beauty and Culture, written by Kasia Maciejowska and edited by ICA Executive Director Gregor Muir.

The shop embodied an unpolished, narrative, low-tech, dystopian, masculine, radical and postmodern aesthetic. It was specifically urban and expressively communicated the personal experience of living as a young person with artistic aspirations and little income in a post-industrial city. Both the building itself and the objects sold there represented the way in which a generation of countercultural Londoners shaped their identities and attempted to make a living from the innovative reuse of the resources to be found in the city’s cracks.

"The building and the objects sold there represented the way in which a generation of countercultural Londoners shaped their identities."

Individuality—the light-hearted kin of Thatcherite individualism—was king at HOBAC. The craftworks possessed different discernable characters, each being intimately reflective of the individual personae that made them, so the holistic body of HOBAC was one that contained various materialities, styles and techniques, unified by a shared critical position. It was a collective, and bore all the erraticisms and symbioses that signify communal living as well as collaborative artistic practice.

Carved Objects - Heart of Stone (brick), Mahogany

The majority of production at HOBAC was emphatically about one-offs. The craftwork practised at the workshop made innovative reuse of urban detritus, layering materials and stylistic references to forge an aesthetic that was simultaneously elegiac for a fallen world, signified through the waste materials, and hopeful for the new realities that could potentially be constructed from that wreckage. This interpretive, adaptive and at times subversive approach took its cues from the punk movement of the previous decade. The shop’s contributors had been in their late teens and early 20s during the late 70s when the do-it-yourself countercultural protest of punk gained momentum; all of those involved referred to it as HOBAC’s informing ideology.

Dave Baby, Judy Blame, Alan Macdonald, John Moore and friends in the 1980s. Courtesy Alan Macdonald

When combined with the economically motivated uptake of the existing materials being offered up by the post-industrial decay of London’s East End, this do-it-yourself approach resulted in the creation of works whose stylistic primitivism belied the sophisticated comment they proposed to the dominant economic and aesthetic backgrounds against which they were set. The unpolished brutality of the works, described by their open seams and crude joinery, broken edges, untreated materials and overtly expressive forms, posed as an alternative to the novelty and plasticity of more readily available designed objects during the 1980s, exemplary by their contrast and their nature.

"The unpolished brutality of the works posed as an alternative to the novelty and plasticity of more readily available designed objects during the 1980s."

These details self-consciously evidenced the handicraft processes by which they were built and celebrated the history and patina of the preused materials and pre-perceived references from which they were made. In this sense they were honest, or ‘real’, telling of their own materiality and their construction process, and of the pre-existent forms the materials held before they were reworked.

Knitwear by Richard Torry. Photo: Plastiques Photography. [Top Left]; Post sack jacket by Christopher Nemeth with decorative details by Judy Blame and Dave Baby. Photo: Plastiques Photography. [Top Right]; No Waiting, Loading, Unloading Chair (upholstery from parking meter shroud, found mahogany, foam rubber, by Frick and Frack. Photo: Plastiques Photography [Bottom Left]; Lamp (assemblage of found iron car and machine parts, sand blasted kilner jar, elastic bands) by Fric and Frack. Photo: Plastiques Photography [Bottom Right]

All of those at HOBAC were interested in this idea of the designed object as storytelling or portrait, both of the designer and of the craft process. The shapes of Moore’s shoes, with their square toes or extended soles were derived by mutilating or adapting traditional lasts, an intervention into the conventional craft process that was told through the form. Similarly, Nemeth’s design process entailed the cutting up of existing clothing, as well as of painted canvases, and reformulating them in a way that visibly acknowledged the method by which the reconstructed garment had been produced.

"All those at HOBAC were interested in the idea of the designed object as storytelling or portrait, both of the designer and of the craft process."

Nemeth used his own body in this process, shaping his patterns around his physique and adjusting the sizes to scale in relation to himself, to preserve his personal posture in the garments others would put on, relaying the image of himself onto those who would wear his pieces. Speaking with Gregor Muir in 2016, Blame said one of the best things about Nemeth’s designs was how they reshaped themselves around the body of the wearer over time. Blame similarly learnt his practice through customising clothes on his own body and continued to use himself as a starting point and model throughout the 1980s and later. Macdonald refers to the pieces created there as being portraits of those who made them, describing the creations from the workshop as ‘psychotic and neurotic’, elaborating that Torry’s knits, for example, express a sort of agitation and a representation of his psyche through their body-distorting shapes and how they seem to be on the brink of unravelling.

High heel brooches by Judy Blame. Courtesy Nemeth Archive.

Torry, Nemeth, Blame, Lebon and Fric and Frack all maintained projects outside of HOBAC simultaneously. Blame was styling, Lebon had got Nemeth and Blame’s work stocked at the shop Bazaar, on South Molton Street in Mayfair, respected for its selection of new designers. Torry was stocked at Site, in Soho, and at Browns, and was travelling to Japan frequently, as Nemeth and Blame started to do. In 1987 Fric and Frack moved to a bigger studio space in an abandoned factory across Kingsland Road, which they defiantly dubbed the Fudgepacker (slang for homosexual) Palace so they could craft larger commissions for furniture and set designs independent of Moore’s project.

"It was a shared ethos, rather than a uniformity of style, that united the group."

So, the collaborative shop was only one in a network of representations of their separate designs, but it was the only space in which they were represented collectively. According to fashion journalist and curator Iain R. Webb, it was a shared ethos, rather than a uniformity of style, that united the group. Part of that ethos was to communicate individuality through design, through which a resistant self-conscious criticality could be performed that opposed a dominant culture they felt to be abhorrent in its conservative politics and generic aesthetics. ■

The House of Beauty and Culture, by Kasia Maciejowska, is available in the ICA Bookshop.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events

Tagged with: The House of Beauty and Culture, Design, Fashion, Art, 1980s, Thatcher, Thatcherism, Punk, London, Avant-Garde, Radical Design, Kasia Maciejowska, Gregor Muir

%2c%20Mahogany/index.jpg)

%20by%20Fric%20and%20Frack.%20Photo%20Plastiques%20Photography/index.jpg)