The State of Arts Education Today: Art on the Line

In response to proposed changes to the arts curriculum and following our interview with educators at St Marylebone School, artist and arts educator Rita Cottone shares her experiences and reflects on the importance of the arts.

Something doesn’t quite add up. Mainstream schools across the country are questioning whether to offer Art and Design at Key Stage 4 or 5; some have already closed departments. The closure of PGCE teacher training courses supports this trend. And yet, the other message, the one that acknowledges creativity as fundamental to the success of the future UK economy, is also getting louder. The creative industries have been growing steadily and make a significant contribution to the UK economy: more than £70 billion annually and 5% of UK jobs. The industry saw nearly 10% growth last year.

If the future success of our economy rests upon creativity then why exactly are the arts being sidelined?

Creative Divide

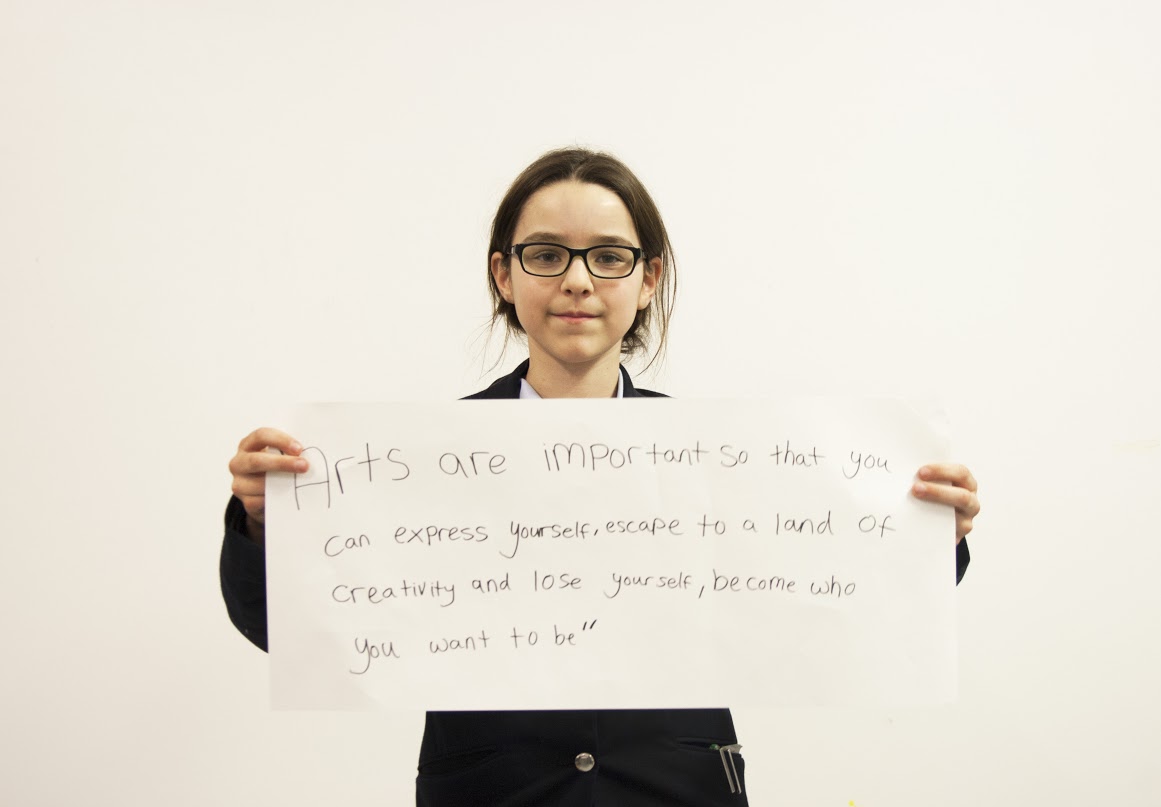

Elizabeth Price, artist and teacher at Ruskin School of Art in Oxford was right to use her 2012 Turner prize-winning speech to attack cuts to arts education. She believed that the introduction of the EBacc would transform the arts and make it almost impossible to have a career as an artist. Fast-forward four years and her words resonate even more. When the message out there is about encouraging creativity, where exactly will we find it once the arts are sidelined by the EBacc? My guess is that they’ll end up within reach of the privileged few who can afford to send their children to extra-curricular classes or fee-paying schools where the arts will still exist.

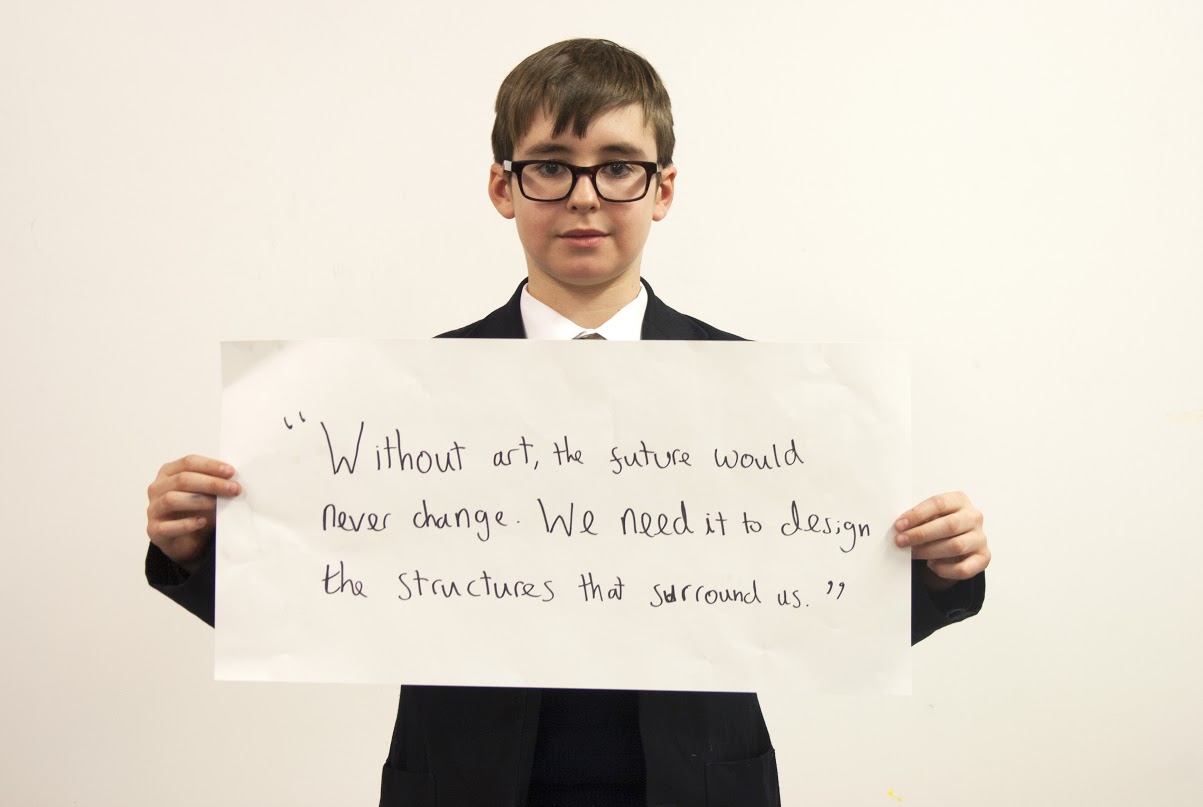

We are told that creative skills can be acquired without the arts on the curriculum. I’m not convinced. The arts don’t have a monopoly on building creative skills but there’s a reason why they are currently compulsory at KS3. What validates the arts’ place on the curriculum and their ultimate strength, in my opinion, is the constructivist, ‘enquiry’ based approach to learning that they foster. Written about extensively by many of the great educational theorists—Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, John Dewey et al.—this type of learning encourages students to investigate their own areas of interest. They choose what to study within the parameters of a set theme and build on their own experience and understanding. Students take more responsibility for their work as they’re so much more connected to it. They persist through knowledge deficiencies in order to achieve a solution. Skills in innovation and idea generation are developed through this process.

It doesn’t stop there. Life-skills such as resilience and perseverance are staples of the arts – setting your own learning and motivating yourself to achieve ambitious goals are not for the faint hearted. Many of my students in art at GCSE and A-Level struggle at the start of the course to break away from the highly ingrained, mimetic way of learning that dominates our education system. It’s great for completing exams but not so good for developing skills in creative thinking and innovation. Having a mixture of learning approaches through a range of subjects on the curriculum is vital for a more rounded development. The arts are a fundamental part of this.

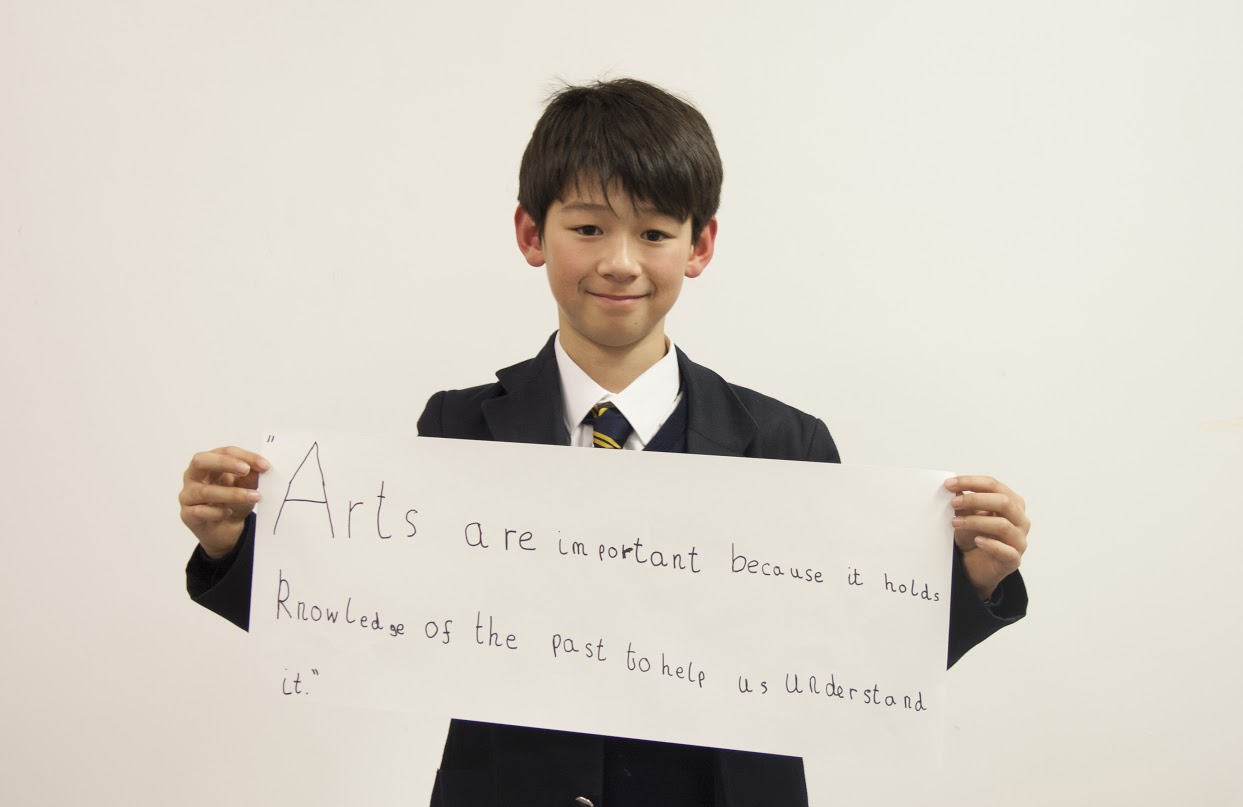

Cultural Access for All

So what can we do to keep the arts on the curriculum? For a start, the Warwick Report’s [PDF] suggestions need to be heeded: a cultural education and equal access to this should be a priority. We need creativity and creative skills more than ever – the facts tell us that. Whether these are embedded across the whole school curriculum or not, the arts need to stand as permanent entities in themselves. Creative talent needs to be recognised. The long line of cultural capital that forms part of our heritage needs to be supported and added to. What are our cities and communities without the arts and what might they become if we stop contributing to them?

If we do continue to sideline the arts, communities will be forced to respond to the fallout. Museums, galleries and other organisations will have to offer more to young audiences. You can take the arts off the menu but the demand will still be there. I worry about this. More community responsibility could be highly beneficial, of course. There is significant evidence [PDF] of the importance of students’ experiencing spaces beyond school such as museums and galleries, as a key part of their education. The research indicates that these experiences can lead to improvements in academic achievement, creativity and general attitude to learning. The research is inspiring, but how exactly will this demand be met?

We might look to an institution such as the ICA which offers a growing range of resources for schools already. It has developed an inspiring film screening programme for A-Level students and partnerships with organisations such as Channel 4 through its project, STOP PLAY RECORD where young students can get involved in filmmaking. The ICA also develops resource packs alongside its exhibition programme, encouraging discussion and activity-based learning. Visiting students and teachers of the arts can fully engage with the works on display. Maintaining and developing these initiatives and resources in arts institutions will be increasingly important if the arts in schools are cut.

Is it too late?

Supporting communities in their efforts to make provisions for young people will not be easy. Just as we acknowledge that cuts to the arts in schools are occurring, funding cuts to museums and galleries are well-evidenced. With both the arts in schools and the arts in public spaces on the line we are putting ourselves in a dangerous position. The Warwick Commission has recognised that reductions to public funding in cultural institutions will cause knock-on effects wherein ‘fewer creative risks are taken, resulting in less talent, development, declining returns and therefore further cuts in Investment’. This will only continue if the arts are sidelined in schools.

Hopefully it’s not too late. I cannot avoid feeling pessimistic, however, when I can clearly see the arts and the subject I teach becoming more and more attacked and marginalised. Provision for creativity looks tenuous and I wonder whether our education policymakers have thought carefully about the future consequences. I hope they have some answers otherwise we are heading towards significant losses for our young people, society and the future. ■

The ICA is committed to the healthy future of arts education in Britain. Our extensive and exciting Learning programming includes offering unique opportunities for young people to take part in programme curation through the ICA Student Forum, engage in a deeper understanding of contemporary art through placements and even gain an MA in contemporary art study. We supplement our national touring programme with workshops and other educational outreach, and we actively support campaigns like Bob and Roberta Smith's Art Party.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Exhibitions, Members News

Tagged with: arts education, Rita Cottone, Art Matters, learning, The State of Education Today, ICA Studentforum, students, Arts Cuts, Government, Policy, Education Policy, Exhibitions, Stop Play Record