Decommissioned: Indifference as Resistance

To coincide with our Decommissioned lecture series, writer Brett Darling responds to Lisa Le Feuvre's lecture, exploring how indifference might be employed as a radical artistic strategy.

"Art is neither good, nor bad. It is not there to edify, enlighten or inspire." To say we should be unafraid of words like these would be to rob them of the necessary vertigo they induce. In the shadow cast by such statements, on what shaky ground does art stand? In her opening lecture of the Decommissioned series, Lisa Le Feuvre, curator at the Henry Moore Institute, offers her response. “Indifference is a position that we can inhabit, a position we can embrace.”

The indifference Le Feuvre offers isn’t the passive sort of the glumly unaffected. Rather, it is a radical position. Its challenge to hegemonic power lies in its very impossibility – as this hegemony, despite the politicisation of art, not only appears to go unaffected, but on closer inspection actually draws its strength from such forms of condoned dissent. This isn’t a story about the political capability of art. The political incapability of art might serve us better.

"I do not consider the audience at all when I make a film, the narrative is not my first thought, there are other ways for a story to make itself known." Hou Hsiao-Hsien

The Assassin, directed by Hou Hsiao-Hsien and shown in the same cinema at the ICA where Le Feuvre made her pronouncement, is a film that consistently defies convention. As a ‘martial arts’ movie it pays very little respect to its supposed genre. It is rather a story told in fragments, a visual poem, which might see at least half of the audience respond with a resounding sigh of bewilderment, while the rest gaze at the credits in amazement. It follows a young, female assassin coming to the end of her training, having been sent away to attain the skills required for enacting the moral law on her return. It is a film in which characters cannot look one another in the eye. It is the story of indifference par excellence, one where the impossibility of occupying such a position becomes its very source and subject. But let us return to our shaky ground.

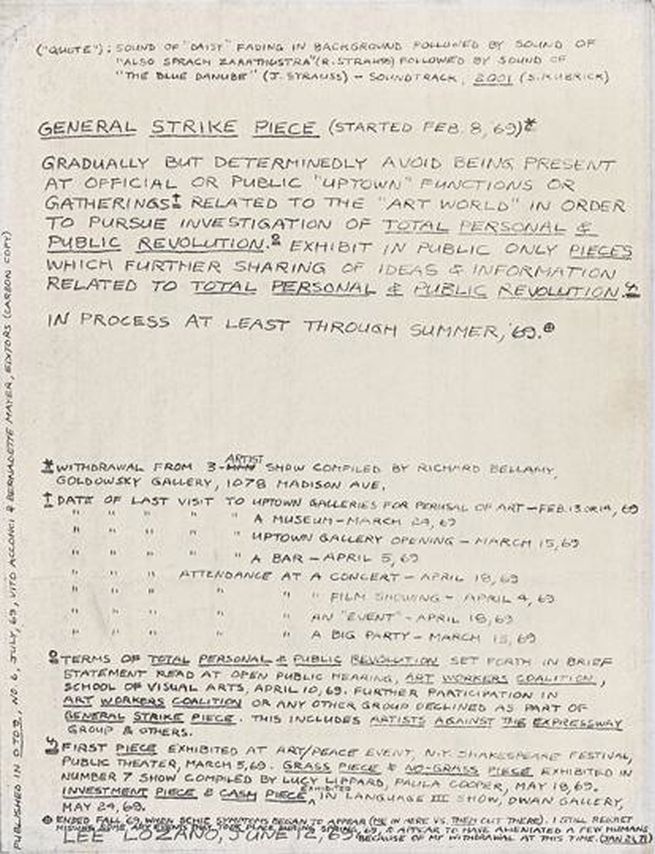

Lee Lozano, General Strike Piece, 1969. Graphite and ink on paper.

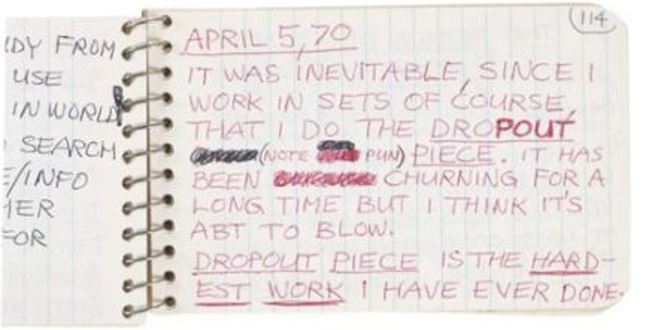

Two of the artists mentioned by Le Feuvre, like our assassin, stepped out into the darkness of indifference. Lee Lozano’s controversial artworks life art, General Strike Piece and a piece which at one point saw her boycotting all verbal communication with women, led to her disappearance from the art world. Christine Kozlov similarly later left the art world as a final form of withdrawal, producing works that explored forms of non-production, such as 271 blank sheets of paper corresponding to 271 days of concepts rejected, and another consisting of a reel-to-reel recorder that taped the surroundings while simultaneously erasing its own content. For Le Feuvre, in their protest at women’s situation in the art world, the works occupy indifference as a position “counter to difference”.

Is indifference always a negation of difference? Or could it be thought of as something more radical that exists beneath difference itself, as a remnant or a trace, something that lurks as the very impossibility of withdrawal?

Lee Lozano, untitled sketchbook page, April 5, 1970

For Maurice Blanchot, as for Hegel before him, to name a thing is to annihilate it: “The word gives me the being, but it gives me it deprived of its being… its nothingness”. By replacing a ‘thing in itself’ with a word, the ‘thing in itself’ is deprived of its being. But out of this very death the thing is reborn. Literature, then, is always caught between two poles, one that acknowledges the inherent emptiness of language—its nullity—and another that must believe in the capability of words to create and to build. With neither position tenable in and of itself, literature is always a failure born on impossible ground.

In The Assassin we find ourselves similarly stuck. Just as the narrative appears to approach clarity, scenes, like unbridled horses, suddenly bolt. A slow scene in which a man stirs a fire in a barn is edited so that a mysterious door creaks off screen, drawing our attention away before any significance is given to it. The view of the camera is consistently obscured by silk drapes or rising smoke, forming a barrier between our view and moments of emotion that, when the assassin comes too close, explode into violence. And yet the action of death here, is also always too quick to take in.

Just as in the film, when the artwork, the word, begins to know itself, it pulls back, it explodes. Is it not here, between these two poles, that we also find Le Feuvre and the radical position of indifference - a position that acknowledges the nullity of representation and yet builds in spite of itself? Both Lozano and Kozlov resurface in our dreams and in our lectures. They remain as traces in scribbled notebooks to be transcribed and decoded by professional art detectives in years to come. Their withdrawal is impossible to maintain; an artwork, stretched even to the end point of absolute withdrawal, retains the very failure of this withdrawal as its source in order to exist. To be indifferent is to be at war with oneself. And yet, to embrace this war is to take a position from which art can be made that transcends the hegemony. ■

Decommissioned is a lecture series, exploring how strategies of disavowal, inactivity and transition are employed in contemporary art and design.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events

Tagged with: Decommissioned, Lecture Series, Lectures, learning, Brett Darling, Stephen Wilson, talk, Talks, Indifference, Radical Art, Art, Lisa Le Feuvre, The Assassin