Poetry, Politics and Polish Surrealism: Żuławski's Last Film

Ahead of our run of Cosmos, Daniel Bird reflects on filmmaker Andrzej Żuławski: his surrealism, his dirsuption of arthouse conventions and the intricacies of his final film.

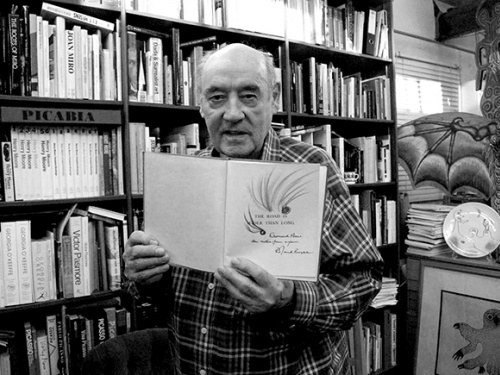

"We are all still under the influence of Gombrowicz", said Andrzej Żuławski. This comment did not arise during a publicity junket for what would be his last film, an adaptation of Witold Gombrowicz’s novel Cosmos (2015). Rather, it was in response to a question I asked eighteen years ago, about the surreal quality of his films.

There has never been a formal Polish surrealist movement as such, but there have been notable fellow travellers such as Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Bruno Schulz, not to mention the author of I Burn Paris, Bruno Jasieński. Jasieński's surrealism emerged from an extremely warped engagement with futurist ideas. According to Żuławski, his own surrealism is the result of pushing the Polish Romantic tendency to excess. Like Gombrowicz, Żuławski's own relationship with Polish Romanticism is far from clear cut. Early in his infamous Diaries, Gombrowicz drives a knife into what remains the Achilles' Heel of his homeland: a perpetual inferiority complex. In it, Gombrowicz berates Polish critics claiming that Thomas Mann took inspiration from Zygmunt Krasiński's Un-divine Comedy. This desire for affirmation from abroad persists and was, of course, the focus of Żuławski's La Note Bleue (1991), along with its unflattering, almost vampiric portrayal of George Sand.

Prior to Cosmos, Gombrowicz had not fared well in cinema. Jerzy Skolimowski's attempt at Ferdydurke (1991) was, by his own admission, a failure, and Jan Jakub Kolski's Pornografia (2003) missed the mark completely. Żuławski's Diabeł (1972), which was banned on accounts of its veiled allusions to police provocations during the Warsaw student riots of March 1968, bears comparison with Gombrowicz's The Marriage, in terms of its dreamlike reconfiguration of familial relations. While shooting Cosmos, Żuławski claimed to have kept a diary, entitled How I Did Not Film Cosmos.

"Żuławski's Cosmos is both tango and wrestling match between filmmaker and author."

Ironically, Żuławski's lack of fidelity towards the text is, nevertheless, true to the spirit of Gombrowicz. This is, after all, an author whose Diaries begin with a string of single world entries: me, me, me. Similarly, just as the murder of Sharon Tate cast a shadow over Polanski’s Macbeth (1971), Żuławski's Cosmos is both tango and wrestling match between filmmaker and author. To be true to a writer predisposed to parody is to parody them in turn. Just as Gombrowicz re-orientated the world around his own ego, so the character of Witold in Żuławski's Cosmos grows increasingly Zulawskian, to the point where the novel the protagonist is writing becomes a screenplay, while the source of all his emotional suffering is an aspiring actress.

The strength of Żuławski's Cosmos is the filmmaker's engagement with, rather than neglect of, his source material. For all its excesses, L'Amour braque (1985), Żuławski's BD styled transposition of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, chimed with ideas in contemporary French literary theory (Mikhail Bakhtin by way of both Julia Kristeva and Tzvetan Todorov). Whether it be Étienne Roda-Gil's gutter poetry, or the director's own rhyming verse in Mes nuits sont plus belles que vos jours (1989), Żuławski's surrealism is as verbal as it is visual. At its best, Żuławski's Cosmos revels in visual rhymes and rhythms, both in the text and suggested by the text. If, like Sergei Parajanov's The Colour of Pomegranates (1968), Żuławski's film is as much about his subject as it was about himself, then just as Parajanov developed a cinematic analogue to Sayat Nova's poetry, Żuławski achieves a filmic equivalent to the sheer weirdness of Gombrowicz's prose. One aspect of Żuławski's cinema which has consistently been ignored is his politics.

"Żuławski's surrealism is as verbal as it is visual."

Whereas the political in Andrzej Wajda's cinema is consistently explicit, Żuławski's approach, by comparison, has always been oblique. The same year in which Wajda's Man of Iron (1981) was awarded the Palme d'Or, Żuławski's Possession (1981) told the story of an idea taking physical form which in turn kills people. Żuławski returned to the same theme in La femme publique (1984), which in turn alluded to both the assassination attempt on John Paul II and Fassbinder's association with left wing extremist groups. Similarly, it is worth noting that Cosmos, Żuławski's first film in fifteen years, hit French cinemas just over a month after Poland's Law and Justice party (PiS) took full control of the Polish parliament. Whatever one's feeling about Cosmos, one cannot ignore the gesture – Żuławski, filming Gombrowicz, now. Gombrowicz signifies the antithesis of everything PiS stands for: an emigre, one critical of Polish nationalism, and open about his sexuality.

Last year in Locarno, Żuławski was awarded the Golden Leopard for best director. If leopards cannot change their spots, Żuławski never sought in Poland or France to be part of clubs that would accept him as a member. John Waters wrote of Todd Haynes' Carol (2015) that perhaps the only way to be transgressive today was to be shockingly tasteful. Cosmos isn't that, but it cheerfully subverts certain stereotypes relating to contemporary 'art' cinema: it is energetic, playful and verbose. It ends with a formal manoeuvre that allows the viewer to have their cake and eat it, one which reconciles a desire for happy endings with Gombrowicz's inability to end (i.e. the Diaries). Żuławski’s ending is the opposite of every Judd Apatow film, when the hero 'grows up'. Whether it be Diabeł or L'Amour braque, Żuławski's cinema hinged on youth, innocence and nativity cast adrift in an indifferent, harsh and unforgiving world. The ending of Cosmos is Żuławski's most succinct re-iteration of this theme: the triumph of immaturity, beauty, madness over maturity, ugliness and sanity. ■

Cosmos runs from 19 August.

We are always looking to hear from potential contributors. If you would like to pitch a feature for the ICA Bulletin email blog@ica.org.uk.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film

Tagged with: Andrei Żuławski, Cosmos, Gombrowicz, Film, Films, Film Director, Surrealism, Romanticism, Poland, Polish Film, Daniel Bird