Cultural Liberation Springing From Physical Liberation: Reception Study of the 1980s Avant-Garde

How have changes to the female silhouette in fashion reflected and shaped perceptions of beauty? In this abridged extract from Fashion Game Changers: Reinventing the 20th-Century Silhouette, Hettie Judah explores the relationship between the social and political changes of the 1980s and the fashion of the time.

In our event Culture Now: Refashioning the Female Body, which marks the publication of the book, she chairs a discussion investigating the transformations of the female silhouette during the 20th century that challenged established notions about beauty and femininity.

The divergent fashions of the early and mid-1980s were close-coupled to widespread social and political changes in the era. While styles that are now iconic of earlier decades of the twentieth century in truth represent the sartorial choices of only a small, turned-on zeitgeist – be that the hippies of Haight-Ashbury or the swinging Londoners of Carnaby Street – the 1980s ushered in the contemporary era of mass, global fashion trends.

Paris’s status as the home of fashion may have been challenged by styles emerging from the US and UK in the 1960s and 1970s, but these represented waves of influence from youth and counter-culture, rather than high fashion. A more serious blow to Paris’s crown came from Italy in the late 1970s, where a new generation of ready-to-wear designers – notably Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace – started showing innovative collections that in their deployment, respectively, of masculine tailoring and powerful sexuality, held strong appeal for the emerging class of independent working women. The woman’s body as a sexual weapon was likewise suggested by the ultra bodyconscious designs of Paris-based designers Azzedine Alaïa and Thierry Mugler.

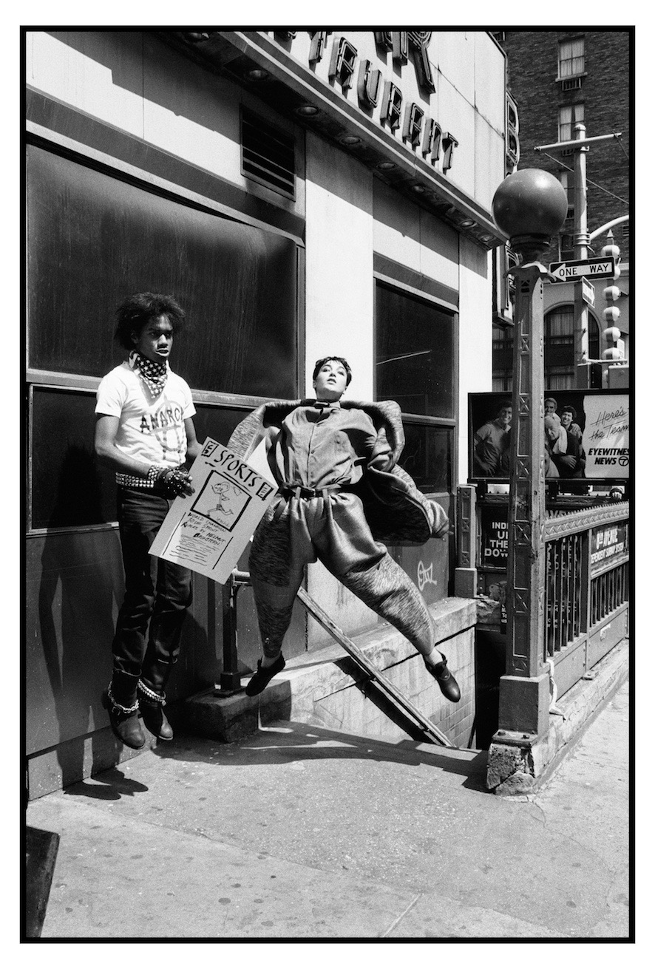

"London’s fashion culture revolved around a post-punk DIY ethos rooted in squatter culture."

Just the other side of the English Channel, but spiritually far divorced from the lusty glamour of the Parisian catwalks, the UK was suffering both from the long tail of the global economic crisis of the late 1970s and the impact of political turmoil, the combination of which led to mass unemployment. London’s fashion culture revolved around a post-punk DIY ethos rooted in squatter culture and characterized by the zine-like street-centric aesthetic of i-D magazine, which launched in 1980.

It was into this sociocultural milieu that Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons launched themselves when they presented their work for the first time in Paris in 1981. Both were well established in Japan – Kawakubo had founded her company in the late 1960s following stints in advertising and styling; Yamamoto established Y’s in 1972 a few years after graduating from Bunka fashion college in Tokyo – and together they presented a fully realized vision of the female wardrobe strongly at odds with the form-flattering femininity associated with Parisian high fashion. Their first – joint – presentation, shown to an audience of some hundred or so press and buyers, was composed of loose, layered, voluminous garments in black, abraded fabrics which were knotted or wrapped around the body, creating layers, contours, lumps and folds in unconventional positions.

"The question of the female figure and its exhibited fitness was one central to concerns of female and feminist discourse in the era."

Issey Miyake, who had been showing collections of formally and technically experimental clothing in Paris since 1973, has referred to the approximate contact between the body and the garment in his designs as ma – the concept of space between body and cloth that allows flexibility and movement. While the frayed and loosely stitched designs of their early Paris presentations were aesthetically far removed from Miyake’s at this stage, Yamamoto and Kawakubo’s designs shared this interest in volume and of creating garments for the body in motion. Shown with flat shoes, and (as some journalists remember it) combat boots, on pale, minimally made-up models who strode rather than sauntered, they represented a forceful antidote both to the traditions of Parisian high fashion and to the more exuberant, sexy styles of the time.

***

The question of the female figure and its exhibited fitness was one central to concerns of female and feminist discourse in the era. The idealized ‘New Woman’ of the 1980s was immersed in the world of work, she signalled her status, discipline and power through her athletic, gym-toned frame. She wore clothes that emphasized her hard-won shape through the cling of Lycra, and accentuated her ambitions to succeed in business through padded shoulders that aped the contours of a man’s business suit. Aggressive ambition was celebrated, as was the display of status through expensive clothing and accoutrements. As for sex? Gym-buffed ‘New Woman’ was available and up for it: as in control of her sexuality as she was her career.9 What she was perhaps not, explicitly, was a feminist. Thanks to what became known as the ‘sex wars’, feminism was becoming a troubled term. As the ‘second wave’ of feminism fragmented into disputes about sexuality and body politics, the word was increasingly associated with hostile attitudes toward men, socialist ideologies and ‘political’ lesbianism, all of which was gleefully transformed by the mainstream press into a portrait of humourless militancy.

Writing in British Elle in 1986, the women’s editor (and former fashion editor) of left-wing newspaper The Guardian described the troubled relationship socially and politically engaged women of the era had with the fashion industry. ‘…[M]y morning mail would contain disquieting little nuggets like “Guardian women have better things to do with £26 than spend it on a pair of sunglasses…” and “Guardian women despise fashion as a tool of patriarchal expression. If Brenda Polen is too stupid to realise that, she should be sacked instantly.”’ Polen noted that studies made by the newspaper into its readership suggested that in fact the ‘vast majority’ were interested in fashion, and went on to caution that ‘unsightliness was not next to political purity.’

"The designs of Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo in the early 1980s questioned not only what a woman should look like and how she should dress, but also why, and for whom."

Kawakubo for her part was outspoken in her dedication to provide clothes for hardworking women: ‘The goal for all women should be to make her own living and support herself, to be self-sufficient. That is the philosophy of her clothes. They are working for modern women. Women who do not need to assure their happiness by looking sexy to men, by emphasizing their figures, but who attract them with their minds.’

***

In rethinking the gender binaries, and the passive relationship to clothing that demanded that you conform to it rather than it to you; in breaking with fashion conventions that prioritized youth, athleticism, and a narrow ideal of beauty; in making fashion that presented a body ready for action rather than a body inviting sex; in permitting soft, collaborative power rather than hard ambition, the designs of Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo in the early 1980s questioned not only what a woman should look like and how she should dress, but also why, and for whom. ■

This is an abridged extract from Fashion Game Changers: Reinventing the 20th Century Silhouette (editors: Karen Van Godtsenhoven, Miren Arzalluz, Kaat Debo, Bloomsbury, 2016).

Culture Now: Re-fashioning the Female Body is on 22 April.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events

Tagged with: Fashion Game Changers: Reinventing the 20th-Century Silhouette, Re-fashioning the Female Body, Karen Van Godtsendhoven, Miren Arzalluz, Kaat Debo, Comme des Garcons, Yohji Yamamoto, Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake, Thierry Mugler, events, Feminism, 1980s, Avant-GardeFashion, Hettie Judah