The Cost of our Quest for Development

Zhao Liang's Behemoth

Ahead of our Frames of Representation film festival screening of Behemoth and Q&A with director Zhao Liang, film critic, festival programmer and screenwriter Tony Rayns reflects on Zhao Liang's powerful documentary, its innovative formal approach and its compelling exploration of the environmental cost of industrialisation.

Behemoth returns to the ICA from 19 August 2016.

No Chinese independent documentary-maker has covered more ground—literally and metaphorically—than Zhao Liang, and his latest film Behemoth takes him into several areas he hasn’t explored before. To begin with, geographically: this is his first film shot in Inner Mongolia, a vast “autonomous region” of the People’s Republic of China. The area where he made the film is a magnet for migrant workers from other parts of China because its coal and mineral resources require a steady supply of labourers for both top-mining and deep-mining. Zhao observes these labourers without comment, letting their faces and damaged bodies tell their stories, but he also observes the huge cost to the environment of their work.

"The industrialisation of Inner Mongolia has created a monster which chews up and spits out its own labour force."

The film shows ravaged landscapes so ‘alien’ they might be on the moon – if, that is, the moon had enough gravity to sustain mountains of shale, rocks and other waste products of the area’s industries. There are glimpses of the grasslands which once defined this region, and of the sheep which once grazed on it. But most of it is now a hellish wasteland, satanic enough to remind Zhao and his French producer Sylvie Blum of Dante’s Inferno. Instead of speaking a commentary, Zhao introduces each section of the film—each new location—with first-person captions paraphrased from Dante’s poetry. Behemoth is an apt title. The industrialisation of Inner Mongolia has created a monster which chews up and spits out its own labour force, the all-too-real equivalent of Moloch in Fritz Lang’s fantasy Metropolis.

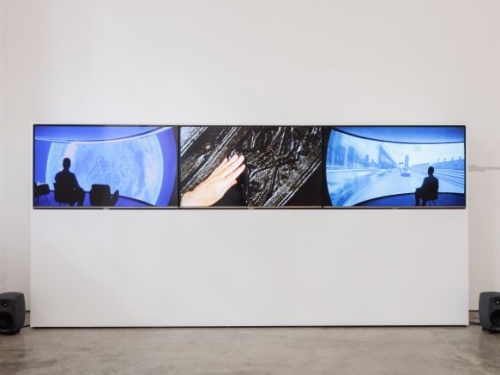

Zhao’s second major innovation in this film is conceptual. It’s probably wrong to suggest that he’s left his reportage style behind, but it’s certainly true that he’s been deploying new ideas in his recent work, especially since his solo exhibition of installations at Documenta Madrid in 2012. Zhao first became known for an intimate, investigative approach, applied to Beijing’s drop-outs and junkies in his first feature Paper Airplane (2001) and to the aggrieved masses from all over China who flock to the capital in the vain hope of winning redress from some elusive official in his magnum opus Petition (2009). A ciné-vérité approach works well in the cinema and on television, but work designed for galleries demands a more imagistic, less narrative approach. Behemoth effectively combines both approaches.

There’s no strong narrative running through the film, but Dante provides the structuring idea of concentric circles of hell. The film moves from one devastated site to the next, starting with top-mining and its massive explosions, moving on to deep-mining, diverting to look at the region’s steel industry, circling back to the coal mines and then visiting a hospital to see the victims of pneumoconiosis; it ends, even more surreally, with a tour of a ‘ghost city’ – a ‘paradise’ of cleanliness. In a sense, Zhao follows the repetitive patterns and rhythms of shift work, sometimes pausing to follow individual workers as they wash, pick at their callouses, and try to live and eat normally in their down-time.

"Zhao Liang has found an ingenious and censor-proof way of registering a protest against inhumane and destructive practices."

At the same time, though, Zhao sometimes stops time to let us contemplate the sheer weight of individual hellish images, and he punctuates his panoramas of the region with staged, stylised images that represent a kind of commentary on what we’re seeing. A Dante-esque figure appears naked, usually curled up in the foetal position, often perched on the ridge of a dark mountain of slag, possibly dreaming. And a Virgil figure, Dante’s guide, staggers across the lifeless terrain with a heavy mirror on his back, reflecting…what? Such images are new in Zhao’s work.

Everybody knows about Xi Jinping’s current crackdown on China’s independent artists, which has seen exhibition venues closed down, artists’ studios demolished and such organisations as Li Xianting’s Film Fund forced to curtail their support for filmmakers. Anyone who directly challenges the rule and authority of the communist party activists, human-rights lawyers—can expect to be silenced and probably locked up. Why this is happening is a matter for much speculation, but most assume that it reflects the communist party’s anxieties about the legitimacy of its rule; even the smallest challenge to that legitimacy must be stamped out. In this climate, Zhao Liang has found an ingenious and censor-proof way of registering a protest against inhumane and destructive practices. That’s the other thing about his choice of title: the Biblical “Behemoth” connotes evil, and what Zhao shows us goes beyond mere laxity about safety procedures and indifference to a region’s ecology. In a quietly devastating way, he reflects the true cost of our unrelenting quest for development. ■

Watch Behemoth at the ICA from 19 August.

The UK premiere screening of Behemoth took place on 26 April, followed by a Q&A with director Zhao Liang.

This screening was part of Frames of Representation, which runs 20 - 27 April 2016.

Tony Rayns is a film critic, commentator, festival programmer and screenwriter. He has written extensively for Sight & Sound, and its predecessor the Monthly Film Bulletin, and previously contributed to Time Out and Melody Maker. One of the world’s leading experts on Asian cinema, he coordinated the Dragons and Tigers competition for Asian films at the Vancouver International Film Festival 1988-2006 and has provided many DVD commentaries and English subtitle translations for films from Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Thailand. He has written books about Seijun Suzuki, Wong Kar-wai and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and has been awarded the Foreign Ministry of Japan’s Commendation for services to Japanese cinema.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film

Tagged with: Behemoth, Zhao Liang, Tony Rayns, China, Inner Mongolia, Frames of Representation, Censorship, Industrialisation, Mining, Documentary, Film, Films, Nowness, Dante