Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s Silent Trilogy: Life and Death in the Times of Revolution

16 Nov 2017 – 25 Nov 2017

The ICA, in partnership with the Ukrainian Institute in London and the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre in Kyiv, Ukraine, presents a retrospective of Oleksandr Dovzhenko's silent film masterpieces – the so-called 'Ukrainian trilogy': Zvenyhora (1928), Arsenal (1929), and Earth (1930). These films were recently restored by the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre, and these modern versions feature new soundtracks created by contemporary composers from both Ukraine and Great Britain.

Dovzhenko is like a gunshot to the face. Taking aim at content and firing at will, utterly free of form. He is unabashedly alone in this. The rest of us like camels in a caravan loping along under this incredible weight of 'form'. To live and work near Dovzhenko is to live near dynamite. It was raw luck that Dovzhenko picked up a camera instead of an axe or a machine gun. His films open fire; they attack without hesitation. - Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein

Ukrainian writer-director Alexander Dovzhenko may be the most neglected major filmmaker of the 20th century. He’s never come close to receiving his due… in large part because his fervent, pantheistic, folkloric films develop more like lyric poems, moving from one stanza to the next, than like narratives, proceeding by way of paragraphs or chapters. The world they describe is one of Gogol-esque horses that sing or reprimand their owners, noble cows, glistening meadows, wily Cossacks, dancing peasants, declamatory speeches by wild-eyed individuals, close-ups of daisies alongside proud women with similarly open faces, vast reaches of empty sky over fields of waving wheat — a vision of a natural order that paradoxically seems both brutal and harmonious. It's poetry in part because it's a paean to existence and because it sings about rather than recounts its details. - American film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum

A world-renowned film director, Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1894-1956) was born into an illiterate Ukrainian peasant family. Hoping for social and national emancipation, Dovzhenko embraced the Ukrainian socialist revolution of 1917. 'I called out slogans at meetings and was as happy as a dog that had broken its chain, sincerely believing that now all men were brothers, that everything was completely clear; that the peasants had the land, that workers had the factories, the teachers had the schools, the doctors had the hospitals, the Ukrainians had Ukraine, the Russians had Russia; that the next day the whole world would find out about this and, struck with our vision, would do likewise,' he wrote later in his autobiography.

Dovzhenko was a witness and an active participant of the turbulent social upheavals in Ukraine in 1917-1921 when six different forces were fighting on its territory: Ukrainians, Bolsheviks, White Army, Poles, Antanta and numerous anarchists units. In fact, the city of Kyiv changed hands 14 times during Ukraine's war for independence. This war was lost, and Ukraine was absorbed into the USSR in 1922.

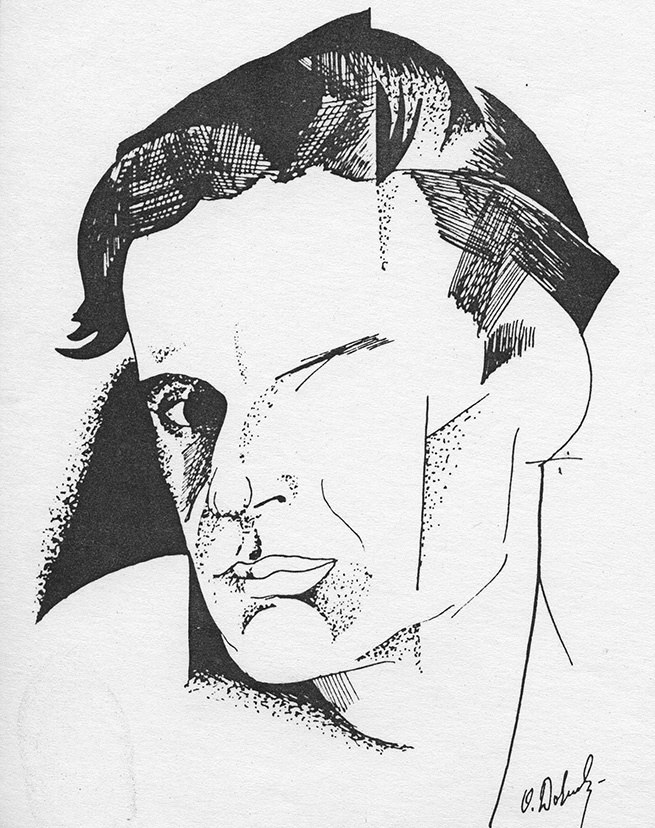

In 1917 Dovzhenko supported the Ukrainian National Republic in its struggle for independence, later to be arrested and imprisoned by Bolsheviks. In 1919 he joined the Borot’bists Party, the left wing faction of the Ukrainian Party of Socialists Revolutionaries, which advocated an independent Ukrainian SSR and played an important role in Ukrainization policies of the 1920s. In 1921-22 Dovzhenko reemerged as a diplomat, first in Warsaw and then in Berlin. Supported by the government grant, he spent a year in Berlin studying painting with Willy Jaeckel, a German expressionist painter. Upon his return to Ukraine, Dovzhenko worked as an illustrator and cartoonist and actively participated in Ukrainian literary organizations. Finally in 1926, Dovzhenko embarked on a career in cinematography.

Along with Sergei Eiseinstein, Dziga Vertov and Vsevolod Pudovkin, Dovzhenko commands a leading role among Soviet avant-garde directors. Praised for its aesthetic qualities, Dovzhenko’s 'Ukrainian trilogy' is considered among the best silent films in the history of the world cinema.

Dovzhenko’s trilogy (as well as Dziga Vertov’s trilogy which includes Man with a Movie Camera, Eleventh and Enthusiasm) was produced by the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Directorate (VUFKU) during two short-lived policies of the Soviet State in the 1920s: the New Economic Policy (known as NEP) and the 'indigenization' policy (known as korenizatsiya), which created a unique environment for the revival of Ukrainian culture. The creation of VUFKU in 1922, powered by its economical and political autonomy from Moscow as well as the emergence of a generation of bold revolutionary artists such as Dovzhenko, Vertov, Ivan Kavaleridze and Heorhii Stabovyi, brought to life a unique phenomenon of Ukrainian experimental film in the 1920s.

In 1929, during the last year of its existence, the Directorate produced almost a third of all films made in the USSR. Having a monopoly on film releases, the company exported its films to the USA, Germany, France and Japan. Then, with a sharp turn in Stalin’s repressive policies, that epoch came to a sudden halt: the Ukrainian Renaissance of 1920s was to be remembered by future generations as the Executed Renaissance. Charged with the crime of nationalism, Dovzhenko himself was forced to leave Ukraine and never returned.

He wrote in his diary: 'I will die in Moscow without seeing Ukraine ever again! In my last days, I will ask Stalin to order, before my body is burned in a crematorium, to have my heart taken out and buried in my native soil, in Kyiv, somewhere on a hill overlooking the Dnieper.'