Poetry, Feminism and the Politics of Translation: An Interview with Sophie Collins

Ahead of the event Currently & Emotion, featuring performances and a panel discussion on poetry and translation, Maya Caspari spoke to ICA Associate Poet Sophie Collins about her writing, tender (the journal she co-founded) and the politics of translation.

When did you first start writing, and how has your writing process and work evolved over time? Do you write with a particular reader in mind?

I've always written stories, but I didn't begin with poems until I was halfway through my first degree. Everyone says they began writing poems in their teens, but I never had this impulse - the closest I ever came was a caustic hate note after an argument with my brother.

I think the process has always remained the same, but I've now got a better sense of what works for me, and of my own tastes. Writing well seems to be about learning what you like in more detail and developing a fiercer conviction. In this sense you are the only reader that matters. You slowly dismantle received ideas of what good writing looks like, find the writers you admire and become confident with what you (want to) make. Of course, the underside of this developing consciousness involves periods of self-doubt, when your work doesn't seem to match your own standards, but these are vital too.

Which other writers, past and present, have influenced you? In what ways do you use other writers, artists and texts in your work?

At the moment I most like certain writers and artists who appear to have distilled so much of themselves that they've ended up with a kind of hermetic, mythologically-driven inner world: Lucy McKenzie, Holly Pester, Chelsey Minnis, Lucy Ives. Their work is subtly unconventional, and without any very brash conceptual gestures to attempt to qualify its awkwardness. I find that a lot of male writers I like end up rehearsing over and over again the same successes in terms of their poems, which is ultimately disappointing. What I like about McKenzie, Pester, Minnis and Ives is that they seem acutely aware of this trap, and so their work has a lot of variation but never shows predictable patterns.

I read writers and look at artwork I like when I want to start writing. I also learn more and more about what I like from other writers and artists. Sometimes other texts find their way into my poems, however if I were to use them more explicitly, in a more concerted way, I'd want to do so in the manner of Don Mee Choi, who often imports other writers' phrases, including from theoretical texts. She does so with a somehow incredible absence of pretention.

Katherine Angel writes that tender is grappling with Denise Riley’s claim that “both concentration on and refusal of the identity of “women” are essential to feminism.” Could you tell us more about your motivations for founding tender and how you see it in relation to this comment? How can we address the need to create space for female-identified writers while also calling into question the hegemonic gender categories that have long restricted them? Is this ambivalent ‘concentration on’ and ‘refusal of’ women’s identity productive in itself?

I have a lot of confusion around the concept of gender, but what is clear is that writers and artists with a female identity are discriminated against in their respective cultures. You can see this simply by counting male/female contributors to any mainstream publication/space. (And there's nothing wrong with counting - counting is a very useful tool.) When I say 'discriminated against' I don't mean that this usually happens directly, though of course it can do, whether the arbiters have enough self-awareness to recognise it as such or not. There are many excellent articles online and in books that cover this from many different angles. Look at the VIDA website, look at essays, novels, stories, interviews online and offline by Denise Riley, Katherine Angel, Sherry Simon, Louise Bernikow, Diane Hamilton, Eunsong Kim and Maya Mackrandilal, Jenny Offill, Joanna Russ - the list goes on...

So, we founded tender in order to provide a concentration of work from an underrepresented minority within the arts. I think that's fine, don't you?

Is feminism important to the way in which you define yourself as a poet, and to your poetry? I was struck by your poem Healers, for example and the way in which you personify the scaffold as female – what was behind this choice?

Honestly there was no conscious choice here - the poem, the scaffold just happened that way. I've been asked this question a few times and each time become more aware of the fact that a masculine pronoun would have flown completely under the radar.

That said, I do feel that at some time following the writing of that poem I began to consciously write female anti-heroes. Increasingly I also like to show disrespect to a certain type of male person in my poems - it just seems funny to me given that these guys dominate the space the poems manage to infiltrate. But I don't explicitly connect the identities of poet and feminist at this point - there's no instruction in my poems and I don't want there to be. In another way, the poems are bound to be in some way feminist because I made them. (I think all of this relates back to what Katherine said about tender.) I do however work on feminist prose and criticism, specifically feminist translation theory.

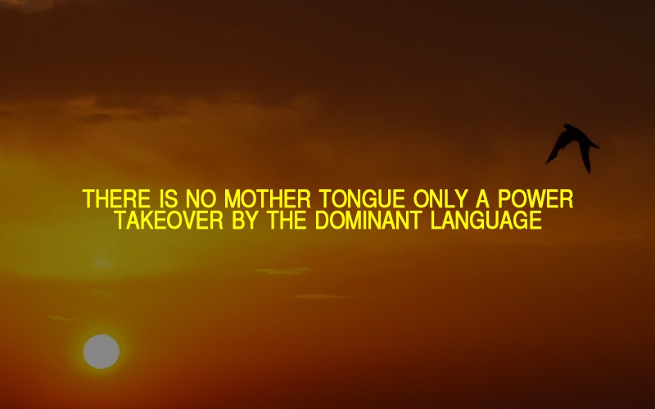

Your upcoming event and anthology Currently & Emotion explores the translation of poetry, and the image accompanying the event bears the text “there is no mother tongue only a power takeover by the dominant language”. Is translation necessarily political? Does the translator have a responsibility to draw attention to the ‘difference’ of the original text?

These are both enormous questions that represent research I've been doing over the past three-and-a-half years. With the first I want to say that yes: all translation is in some way political. Translations have historically shaped, and continue to shape, our perceptions of the parameters of culture. Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere put forward a definition for translation as “the study of the manipulation processes of literature”, and I think this is really effective.

Translations can enrich a given literary culture by introducing new concepts and approaches to writing, but it's also a tool that's been wielded for colonial purposes, contributing to the ways in which we attenuate non-Anglophone identities, specifically non-white ones. I think it's also important to consider what is untranslated, and why it remains so.

Translation is often perceived as a neutral endeavour—a kind of literary service—and, as a result, translators are chronically marginalised within literary culture. I associate this marginalisation very strongly with feminised, domesticated labour. But I believe that developing an awareness of the shaping power of translation on culture is absolutely vital to an awareness of the world in which we live. As a practice and theoretical framework, translation is key to a deconstruction of a hegemonic (literary) culture, and I'm baffled and disappointed by poets who are vocal on our issues with race and gender while overlooking translation as a factor - all are deeply interconnected.

The text on the image we used for the event page—“there is no mother tongue only a power takeover by the dominant language”—comes via Don Mee Choi via Deleuze and Guattari and their A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972) [PDF]. I think this goes back to Bassnett and Lefevere's definition of translation as manipulation, and to the issues of cultural transmission explored by theorists like Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Tejaswini Niranjana.

At the level of 'difference', much of what we see reaching the mainstream of poetry in terms of translation is culturally repetitive, generic work. Poets often take on texts that appear in recent English translations ten times over and from a very limited pool of resources - European or Classical. They don't bring anything new to the translation or reflect on their process in any interesting way. They can't see the translator in a broader cultural context, and so they certainly can't see the complexity of the discussions already occurring within translation culture, and the brilliant projects happening there. I think we should be more critical of this kind of ignorance, and also speculate on their motives. I believe translations are often undertaken out of interest, but carried through in order to increase cultural capital by enabling these poets to attach their names to the authors of the source texts. Though he was talking about a different situation, Gonzalo Aguilar writes in a piece for Asymptote that,

"In this type of translation – which, to distinguish it from mediating translation, we can term possessive – the poet attempts to unite their own name with that of the poet being translated, and become their 'natural' addressee in the target language."

I think it's really vital to encourage the same kind of self-reflexivity with respect to the sourcing of texts that we do in terms of the translation strategy: what is the power dynamic between you and your source text? Why translate this text? Why now?

With the growth of the digital, there are new opportunities for emerging poets to publish their work themselves. At the ICA, the Associate Poet residency places poetry once again at the heart of the institution’s programme. Do you think we are seeing positive changes in the perception and dissemination of poetry?

It's an interesting time for poetry. I don't know if the changes are necessarily 'positive', because I'm not sure how you would go about evaluating them...

Actually, I've changed my mind just now thinking about it. The changes are definitely positive, but I'm thinking more in terms of what's happening in poetry with respect to the dismantling of hegemonic structures, than in terms of contemporary art's renewed interest in poetry - both stimulated by online culture. Claudia Rankine just told a guy to sit down during a Q&A on national radio when he tried (very unsuccessfully) to convert his discomfort with aspects of her work into some kind of universal aesthetic value.

Adrienne Rich, from her essay When We Dead Awaken:

"It's exhilarating to be alive in a time of awakening consciousness; it can also be confusing, disorienting, and painful. [...]

Re-vision – the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction – is for us more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival. Until we can understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves." ■

Currently & Emotion takes place on 17 November, as part of Sophie Collins' ICA Associate Poet residency. As a response to the growing intersection between art and poetry today, the Associate Poet programme continues a long-standing interest and engagement with language and poetry throughout the ICA’s history.

This article is posted in: Blog, Events, Interviews

Tagged with: Sophie Collins, ICA Associate Poet, Feminism, Translation, poetry, Literature, events, The Politics of Translation, interview, Maya Caspari