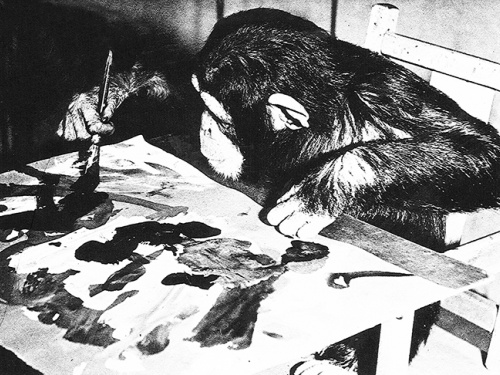

Playground of the Avant-Garde: Desmond Morris on Post-War Rebellion and the Origins of the ICA

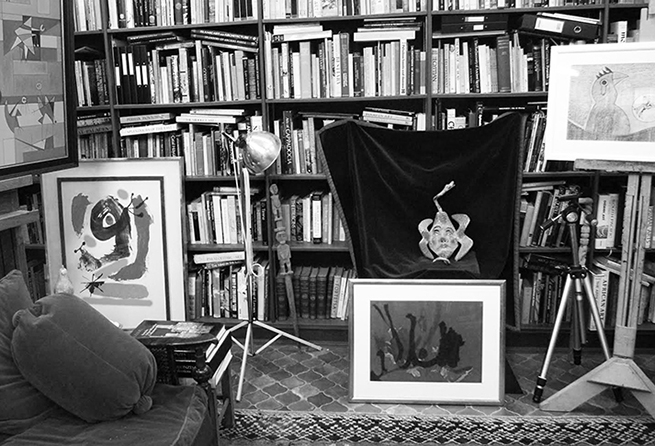

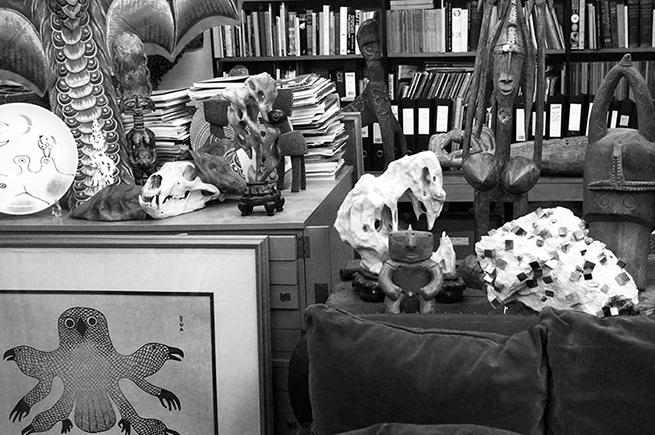

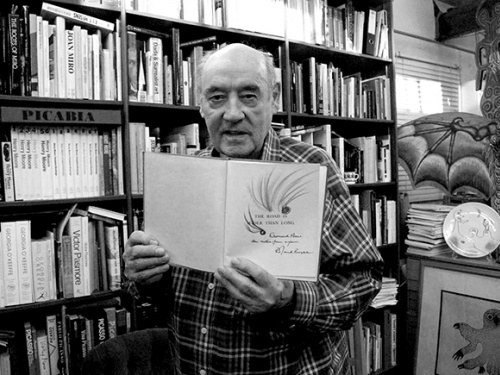

Surrealist painter, zoologist and best-selling author Desmond Morris is known for an impressive list of accomplishments, including being director of the ICA in 1967. Now 88 years old, Morris met with artist and writer Melanie Coles in his Oxford studio to recount his times at the ICA, a place he describes as ‘the seat of rebellion’, home of the surrealists and 'playground' for the avant-garde.

This three-part edited transcript Chimpanzees, Controversy and Contemporary Art: A Conversation with Desmond Morris offers a unique personal insight into the ICA’s subversive origins, recalling first-hand encounters with the legendary characters who roamed the ICA from Herbert Read and Roland Penrose to Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Allen Ginsburg and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The 20th century was a period of rebellion in art. Before all this, one of the major purposes of art had been to record: portraiture or landscape, or scenes that told us what the world was like. It was only when photography was invented at the end of the 19th century that the artist was set free. You didn’t have to have your portrait painted, you could have a colour photograph of yourself which would be more accurate than what any artist could produce. Artists could suddenly try unlimited forms of visual creativity - they could do anything they wanted to and they did. They suddenly began to explore visual representation in a way that had never been done before. The 1920s, 30s and 40s were a really exciting period.

Then the second world war came in and put a terrible damper on things. Everything kind of stopped. It was after the war ended that ICA founders Roland Penrose and Herbert Read, in an extraordinary step really, said, “We have great artists in this country but they need encouragement.” The ICA kept alive a physical place for the experimentation and rebellion that had been abandoned during the war. At that point the traditionalists still held strong control in the UK. The Royal Academy was refusing any sort of modern art. This made Henry Moore so angry that later on when the Royal Academy started to allow modern art I said, “Henry, you’ve never exhibited at the Royal Academy” and he said, “I wouldn’t touch it with a pole.” He was a very quiet chap but if you got him on something like that he was totally antagonistic. Back in the 1950s there was still a very formalistic view at the RA. It wasn’t until the 60s that things started to change. That was to some extent due to the ICA.

"The ICA kept alive a physical place for the experimentation and rebellion that had been abandoned during the war."

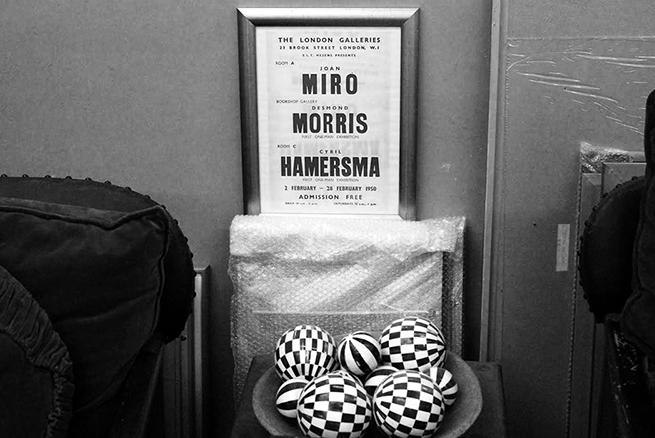

When the ICA first began just after the war, the exhibition of modern paintings was financially disastrous. Miro and I were exhibiting together in London in 1950 and nothing was selling. The paintings that today go for literally millions you could have bought for peanuts then, but nobody was even bothering to buy them for peanuts. The war had drained everybody. People weren’t in a mood to experiment. They were just in a mood to recover. It was a period of austerity and spiritual exhaustion brought about by the horrors of World War II. The whole of Europe was in ruins.

When I went to Paris, all I can remember is the smell. They hadn’t even started to sort out the sewers and the streets smelled terribly. I thought, "God this is awful." I was visiting all the places where all the avant-garde artists had been before the war, the Cafe du Dome, etc. and there was nothing there. It was all empty. The artists had left and it was a very sad time.

"When I went to Paris, all I can remember is the smell. I thought, God this is awful."

So, you’ve got to remember that this was the atmosphere in which the ICA started - it makes it even more extraordinary. It was a time when everybody had lost interest in rebellious avant-garde artistic activity. People just didn’t want to be bothered with that. The world was just licking its wounds. There was food rationing, there was clothes rationing, petrol rationing. It was a terribly wretched time.

I was a young soldier, going up to London to see exhibitions. When I found ICA’s first show 40 Years of Modern Art, I thought, "Oh, what’s this new institute? This is fantastic - there is somebody in London who is actually encouraging artistic rebellion and the avant-garde is still alive!" In the first and second exhibitions the ICA held, all the works were pre-war - from the 30s. Today they are all looked at as old masters but in those days a painting by Max Ernst had no value at all.

These were just things Roland brought out of his cupboards. It wasn’t until the next exhibit that they began showing post-war work. In 1951, they had an exhibition of Roberto Matta, the Chilean surrealist. Then Wilfredo Lam in 1952. Today they’re known as two major artists but they were completely unknown then. In 1957 they had an exhibition of Australian Bark paintings that had just been discovered and William Turnbull had a show. As a young surrealist I was starved of anything like this, so it was wonderful they were able to do it.

"Miro and I were exhibiting together in London in 1950 and nothing was selling."

The creation of the ICA was against the tide which was extremely brave. Its bravery made its mark in those early years. I think it’s a difficult problem now, because galleries like the Tate are doing what they wouldn’t have in those days and are prepared to put on very avant-garde exhibitions. What the ICA did was keep the avant-garde alive at a time when everybody wanted to kill it off. In the 1960s, New York became the centre of the avant-garde art world. A lot of the most exciting work was being done in America. Paris sank, there was nothing happening there. Up until the war, Paris had been ‘it’ and it had been probably for at least 100 years, going right back to the impressionists and even earlier. Geography is less important now. London has done very well, but if we look to see where the avant-garde is today, it’s all over the place. It’s China and Japan, its spread around the world; there isn’t a centre.

The ICA has to now think hard about how it can maintain its early tradition of being the seat of rebellion. My experiences in the early days have lived with me for a lifetime. It was a very special place for me. And of course, I was lucky because that I met so many artists through being there. I was so lucky to meet people like Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Sydney Nolan, Barbra Hepworth - the list goes on and on. ■

This transcript is the first of a three-part series Chimpanzees, Controversy and Contemporary Art: A Conversation with Desmond Morris based on an interview by Melanie Coles with Desmond Morris at his studio in Oxford, UK, 2016, and edited by Melanie Coles and Maya Caspari.

2016 is the ICA's 70th Anniversary. To help celebrate our anniversary, we have put out a call to members for any further stories or archive material from the ICA’s illustrious past, in order to record the ICA’s incredible history. Any material should be shared with archives@ica.org.uk.

This article is posted in: Articles, Exhibitions, Interviews

Tagged with: Desmond Morris, ICA History, Archive, From the Archive, Archives, History of the ICA, History of Art, Melanie Coles, Roland Penrose, Herbert Read, Second World War, Max Ernst, Roberto Matta, Wilfredo Lam, William Turnbull, Henry Moore, Avant-Garde, Maya Caspari, Chimpanzees Controversy and Contemporary Art: A Conversation with Desmond Morris