Luis Buñuel and the Cinematics of Terror

Ahead of our panel discussion on the spectre of terrorism in Buñuel, Eleanor Careless explores the representation of terrorist violence in his work.

Author's note: I began to write this blog post before the recent attacks in Paris, Baghdad, Beirut and now Mali. Knowing the proximity of these attacks to the content of this post, I want to acknowledge all the shock and grief which cannot be translated into art.

Film that responds to or represents terror may record, documentary-style, the activities of terrorist groups, as in The Baader-Meinhof Complex; dramatise the conflict itself, as in recent movies such as Zero Dark Thirty and Yann Demange’s ’71; inscribe ongoing trauma, as in Elia Suleiman’s Palestinian trilogy; or satirise the impulses and responses to terror, as in Chris Morris’ Four Lions and the films of Luis Buñuel. Terrorism is, like cinema, visual, theatrical, and performative, a kind of political shock theatre. Much attention is paid to media representations of terror, but far less to the cinematic contexts which also shape our popular understanding of terrorism today. Guy Debord wrote in 1967 that “the history of terrorism is written by the state”. By turning to Buñuel’s own transgressive political shock theatre, we can find an alternative account of this history which escapes the confines of state-sanctioned rationality.

Born in 1900 in a small Spanish town, Buñuel was more than a bystander to decades of violent conflict in Europe. Terrorist violence was everywhere, from the fin-de-siècle anarchists who threw bombs into crowded theatres, cafes and chambers of government to the White and Red Terror of the Spanish Civil War to student uprisings and urban guerrillas such as Germany’s Red Army Faction and the Italian Red Brigades of the late 1960s. In 1929 Buñuel joined the revolutionary Surrealist movement, for whom “the simplest surrealist act”, according to leader Andre Breton [PDF], “is walking into a crowd with a loaded gun and firing at random”. During the Spanish Civil War Buñuel worked as the co-ordinator of film propaganda for the Republic. Franco’s victory saw Buñuel effectively exiled from Spain. While checking locations for The Milky Way, Buñuel witnessed the 1968 student uprisings in Paris and drew explicit parallels with their aims and those of the Surrealists of the 1920s and ’30s. These events, from surrealist manifestos to urban bombings, shaped the course of Buñuel’s filmmaking.

The aesthetic terror advocated by Breton certainly seems to be the tactic behind the grotesque slashed eye of Un Chien Andalou (1929), which Buñuel made in collaboration with the Surrealist par excellence Salvador Dali. Buñuel attended the first screening of Un Chien Andalou with stones in his pockets ready to attack any hecklers, only to find that the bourgeois audience were delighted by this spectacle of surrealist violence. While this reception is often read as a commodification of the surrealist spectacle, this sensational short film continues to agitate its viewers and vitally habituates its audience to a radically irrational mode of perception. Yet it was the increasingly socially-directed satire of Buñuel’s films from L’Age d’Or (1930) to The Milky Way (1969), combined with unpredictable episodes of surrealism which continued to violate conventions of spectatorship, that far more literally ‘terrorised’ the values of the bourgeois society the Surrealists set themselves against.

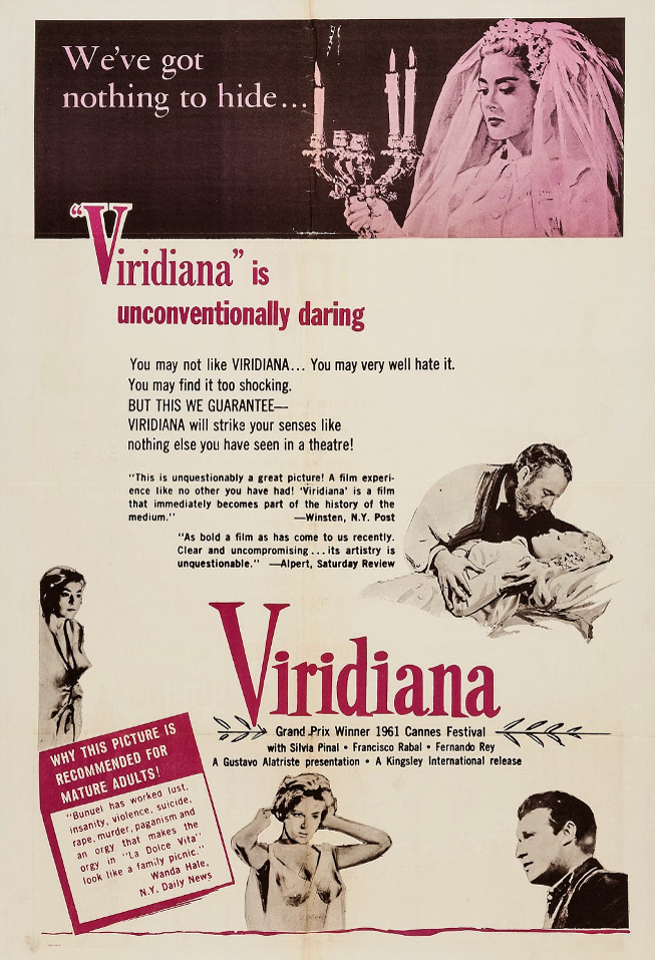

At the time of its release in 1930, the perceived heresy of L’Age d’Or provoked acts of vandalism at screenings and threats of excommunication, and after being banned by the Parisian police, all prints were taken out of circulation until 1979. In 1933, the satirical Spanish ethnography Las Hurdes was banned by both Republican and Nationalist governments. Los Olvidados’ (1950) unrelenting portrayal of poverty in Mexico City precipitated calls to revoke Buñuel’s Mexican citizenship, and the blasphemous Viridiana (1961) (winner of the 1961 Palme d’Or) was denounced by the Vatican and banned for 17 years by the Spanish government. As late as 1969 The Milky Way was banned by the Italian government, again for heresy. The targets of Buñuel’s satire ranged from the Roman Catholic establishment (in L’Age d’Or, The Milky Way and Viridiana) to the masculine ego (in Él) to the purportedly objective genre of ethnographic documentary (as in Las Hurdes). Rather than conform to the indiscriminate act of surrealist violence advocated by Breton, Buñuel’s films take careful aim, not into the crowd but at the powerful.

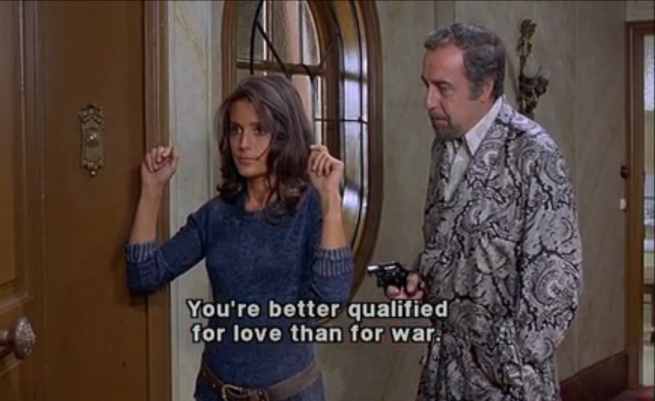

It is not until Buñuel’s final films, made after the advent of international terrorism in the 1960s, that the figure of the terrorist appears explicitly. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) are haunted by a form of terrorist violence that closely resembles the guerrilla groups of the late 1960s. In The Discreet Charm, a terrorist group pursue the lecherous ambassador of the fictitious Latin American country Miranda. These terrorists are represented by a young woman who at first conceals her true purpose by pretending to sell soft toys in the street, but later finds her way into the ambassador’s apartment where she is disarmed, groped and subsequently abducted by her would-be victim, suggesting a contaminating ambiguity between terrorist and terrorised and between political and sexual violence.

This “beautiful assassin on the street corner” reminded singer and film critic George Melly, writing a 1973 review in The Observer, of the women convicted of belonging to The Angry Brigade, London-based guerrillas who claimed responsibility for multiple bombings in the early 1970s. Rather than standing in high contrast to the civilised social world of The Discreet Charm, this undertow of violence bleeds into its endlessly interrupted sequence of dinner parties and bourgeois ritual.

That Obscure Object of Desire, Buñuel’s final film, stars the provocative femme fatale Conchita, who seems as much a terrorist—forever inciting her infatuated lover to violence—as the subversive groups which perpetrate political terrorism throughout the film. A car bomb, a Tannoy announcement warning of the imminent threat of terrorist atrocities (committed by a gang calling themselves ‘The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus’), police vehicles rushing past and the final, unexplained explosion which swallows up the two protagonists, punctuate this narrative of thwarted desire. Buñuel himself wrote that “in addition to the theme of the impossibility of truly possessing a woman’s body, the [Obscure Object] insists upon maintaining that climate of insecurity and imminent disaster – an atmosphere we all recognise, because it is our own.” We never know whether these explosions—which go largely unremarked upon by the films’ protagonists—are figurative or literal, dreams or reality. “Terrorist violence,” observes critic Cristina Moreias-Menor, “puts a full stop to the entirety of Buñuel's filmography”. To the very end, Buñuel retains an explosive ambiguity that is anathema to most media representations of extremism.

These moments of terrorist violence in the margins of the late films form part of an ongoing surrealist iconography of violence that can be traced back to the aesthetic atrocities of Un Chien Andalou. Buñuel's depictions of violence become ever more absurd, as when the ambassador of The Discreet Charm takes up a telescopic rifle to shoot down a small mechanical toy dog. While popular media was quick to sensationalise the rise of urban guerrillas in the 1970s, Buñuel subverts rather than perpetuates this cycle of social panic. In relegating the terrorist narrative to the margins, this activity is normalised and the more insidious violence integral to the civilised world—the true object of Buñuel's satire—is thrown into relief. “You can’t just arrest people like that!” exclaims one flowered-silk clad protagonist, shortly before The Discreet Charm’s final dinner party ends in a massacre masquerading as a counter-terror operation.

Buñuel was not a lapsed Surrealist. His powerful political satire is founded upon the surreal aesthetics of the irrational, and articulates the potentially devastating slippage between violent spectacle and our precarious civilisation. In his own words, “surrealism has passed onto life. Violence is everywhere.” ■

Following a screening of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie on 3 December, there is a panel discussion on the spectre of terrorism in Buñuel's films with speakers including Ian Christie, Anniversary Professor of Film and Media History, Birkbeck and Julian Gutierrez-Albilla, Professor at the University of Southern California and author of Queering Buñuel. This event is organised by Eleanor Careless, PhD student at the University of Sussex, currently undertaking a placement at the ICA in partnership with the AHRC-funded CHASE, Arts and Humanities consortium for South East England.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film

Tagged with: Luis Buñuel, Terror, Violence, Film, Cinema, Films, Director, Film Director, Article, Eleanor Careless, CHASE, AHRC, CHASE placement, Panel discussion