An Instrument of Poetry: The Cinema of Luis Buñuel

Ahead of our upcoming retrospective Luis Buñuel: Aesthetics of the Irrational, Cinema and Film Programme Manager and season curator Nico Marzano has written this introduction, exploring the director's Surrealism and the unflinching critique of bourgeois morality that runs through his varied oeuvre.

Alfred Hitchcock once said at a Hollywood party that Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) was the best filmmaker in the world. We at the ICA agree and are celebrating with a comprehensive retrospective, spanning from Buñuel's beginnings as a pioneer of cinematic Surrealism to his Mexican period and the legendary films he created at the end of his career.

Buñuel's eclectic filmography forces the viewer to rethink conventional frames of vision, often blurring the boundaries of both the real and the surreal. At the very heart of his cinema is a subversive take on religion and middle class moral hypocrisy. As such, his films were also always accompanied by controversy and censorship.

"I never made a single scene that compromised my convictions or my personal morality" My Last Breath by Luis Buñuel

Born in 1900 in Aragon in the medieval town of Calanda, Buñuel was forced into a strict Catholic education and to study the violin by his wealthy landowner parents. His reaction became rejection: he turned to atheism—"by the grace of God" as he often described his decision—and his films often feature the destruction of musical instruments. The seven years following 1917, passed in the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, were formative. It is here that he developed a friendship with young men who were to become two of the most famous exponents of Spanish culture in the 20th century: Salvador Dalí and Federico García Lorca.

His first film Un Chien Andalou (1929) upsets narrative conventions, distorting the coherence of space and time. Scripted with Dalí and full of polemical hints against former friend Lorca (whose poetic aesthetic was opposed by Buñuel) the film strikes the viewer with a succession of sequences that have no logical link between them. It is dreamlike, disturbing, almost shocking; certainly revolutionary. We witness in a nutshell what Buñuel was - and what he was committed to. His work is provocative and lucid, displaying a radicalism that is the fruit of his experience.

Religion and death are recurring concerns in Buñuel’s films. As he once remarked:

"Politics is mostly disappointing (but not always), religion has always been the absolute disappointment of my life, without a doubt. God never decides to make himself manifest, it is obvious."

Key to the development of his work is the documentary Las Hurdes (1933), a critical look at the poorest and most disadvantaged area of Spain. Shot around the Extremadura region which was suddenly filled with fear and instability after the end of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, Las Hurdes becomes an anti-capitalist, anti-religious manifesto.

Politically committed and fervently anti-Franco, Buñuel decided to immigrate to New York immediately after the Spanish Civil War where he became the head of the department of the Museum of Modern Art and director of Spanish dubbing of American films. Disappointed by this experience, he moved to Mexico where, alongside some great masterpieces such as Él (1953) and The Exterminating Angel (1962), he also made films in which he did not feel completely invested and a few that he called "food" - they merely provided the cash he needed for himself and his family.

It took time before Buñuel was able to fully integrate into the Mexican production system and enjoy the freedom of expression it enabled. The breakthrough occurred only in 1950 with Los Olvidados, an ensemble film about a group of kid slum dwellers that won him the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, just five years after shooting The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (1955), a rare and unknown gem within his filmography.

As part of his growing anti-bourgeois critique, Buñuel cleverly combined the teachings of his great friend and teacher Jean Renoir with elements of French surrealism, creating unique and revolutionary works that led to censorship and condemnation from the Vatican, yet also to widespread and long-lasting recognition.

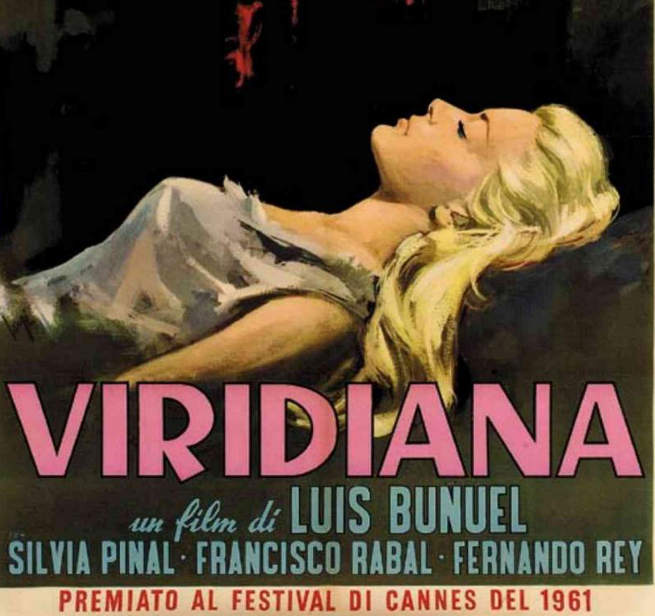

For example, Viridiana (1961) aroused huge indignation from the Catholic Church, gaining Buñuel a conviction in Italy for insulting the state religion. Based on the relationship between a novice and her rich uncle, the film's display of blasphemous details—including the perfect reproduction of The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, all the symbols representing the Passion and overt references to vainly repressed sexual perversions—triggered a major scandal. The first film Buñuel shot in Spain after years of exile in Mexico, it clearly depicts the hypocrisy of bourgeois morality and its approach to sexuality.

"It would suffice for the white eyelid of the screen to reflect the light proper to it to blow up the universe."

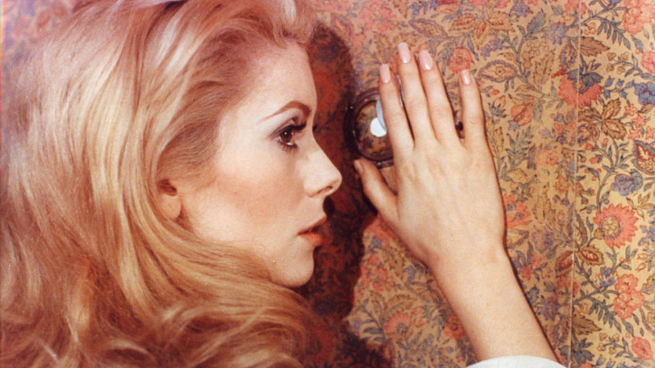

In Belle de Jour, a stunning and detached Catherine Deneuve plays the role of a masochistic prostitute who becomes the perfect embodiment of the dissatisfaction of bourgeois life. Excluded from the Cannes Film Festival, the film was warmly welcomed in Venice where it won the Golden Lion, paving the way for what would be the great masterpiece of Buñuel's mature period: The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972).

Buñuel movies are timeless and challenging; they force the viewer to think. Instead of feeding the audience a basic story, he allows us to figure it out on our own. Throughout our retrospective at the ICA, we're presenting the rare opportunity to discuss relevant aspects of Buñuel's filmography with the people who worked and collaborated closely with the Spanish filmmaker. We hope that the insight garnered though discussions with Jean-Claude Carrière, Diego Buñuel, Maria Delgado, Jo Evans, Peter Evans and Rob Stone will be invaluable. The participation of David Jenkins, Julian Gutierrez-Albilla and Tim Robey represents a fantastic contribution to the understanding of this irreverent and genius filmmaker.

Buñuel’s career was one of incredible consistency and rigour. He kept producing films with his distinctive provocative taste, without ever descending into grotesque irony. He demonstrated the power of film to stage, question and contribute to the destruction of every social convention. ■

Luis Buñuel: Aesthetics of the Irrational runs 12 November - 6 December 2015.

Join the conversation on social media with the hashtag #VivaBunuel.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Events, Film

Tagged with: Luis Buñuel, Film, Un Chien Andalou, Salvador Dali, El, Viridiana, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Belle de Jour, Jean-Claude Carrière, David Jenkins, Ryan Gilbey, Maria Delgado, Jo Evans, Peter Evans, Rob Stone, Surreal, Surrealism, The Exterminating Angel, Las Hurdes, Los Olvidados, Aesthetics of the Irrational, Nico Marzano