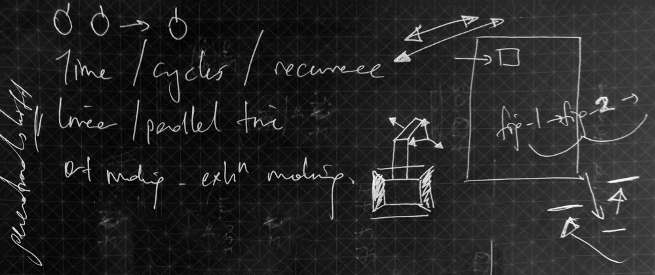

A House with Many Rooms: fig-2

In the final post in our series on fig-2, following its run of 50 exhibitions in 50 weeks, Lawrence Lek reflects on the project's unique temporality.

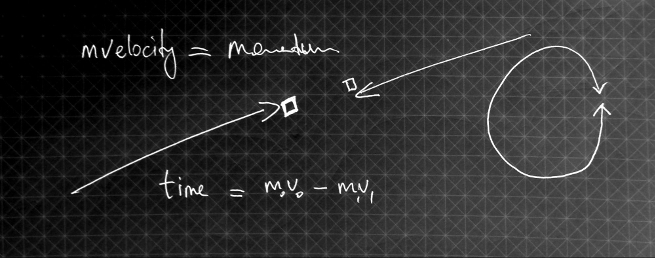

In The Myth of the Eternal Return [PDF], Mircea Eliade’s essay on the cultural psychology of time, the Czech historian notes the differences between the regimented calendars of contemporary life and the cyclical perception of time in early civilisation. Back then, time was perceived in a prehistoric manner. Cosmological cycles governed the passage of events: sunrise and sunset, the waxing and waning of the moon, the changing seasons. This was an infinite cycle, driven by gods who existed outside time. Humans, however, were temporal beings, bound to mortality, to begin and end.

Exhibitions of contemporary art are no different. In order to encapsulate what is happening ‘now’, shows must integrate two contrasting modes of time: the prospective and the retrospective. The continuous search for critical thought guarantees an ever-changing roster of emerging artists, while the institutional need for high footfall requires recognisable artists with significant bodies of work. As a series of 50 consecutive one-week exhibitions in 2015 within an established institution, fig-2 exists in a niche in between major institutional shows and transient one-off projects and events: it is a temporal experiment.

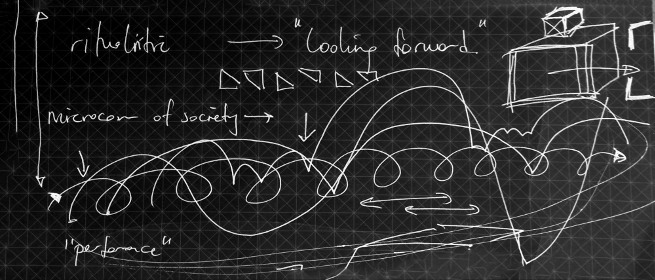

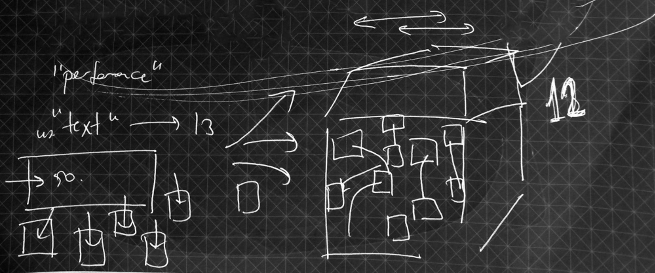

Described by curator Fatos Üstek as a ‘house with many rooms’, the programme unfolded with each project either contrasting or complementing the previous one. Performances followed video, writing workshops followed sculpture. Unlike the monthly or quarterly timescales of institutional exhibitions, fig-2’s weekly schedule was faster, compressed, resembling something more like a weekly club night. (Potential) visitors ask themselves: who is exhibiting? Who is performing? Who is going? By announcing the next artist five days ahead of their exhibition opening, fig-2 created a sense of anticipation. This heightens the pervasive apprehension known on social media as FOMO - Fear Of Missing Out. Seen in its totality, the rapidity of the fig-2 programme is more akin to the refreshing of a browser window.

In 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Jonathan Crary claims that the non-stop processes of capitalist time (which the art exhibition is but one example of) has ruinous consequences. The marketplace is in perpetual motion, pushing us into constant activity and eroding forms of community, agency and political expression. Yet the crux of his argument that constant activity is a bad thing depends on what it is measured against. As an extreme example, Crary illustrates DARPA’s quest to engineer a ‘sleepless soldier’ who could fit into the US military’s plans for increasingly automated systems of surveillance and aggression. These tactics, he argues, could be adapted to a knowledge-based workforce, forced to compete in an increasingly competitive marketplace. As an art historian, Crary could imagine an alternative scenario. Substitute ‘soldier’ for artist or curator or writer and the cultural significance of 24/7 becomes clearer. It is almost a cultural cliche for media to report on the detrimental effects of the creative economy on urban communities, where artists begin a cycle of gentrification that ultimately leads to luxury apartments. Yet this focus on the tangible effects to property ignores how artists and writers—as mostly self-employed freelancers—generate new time-based patterns of work.

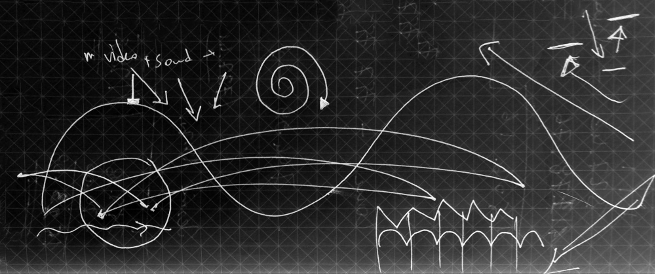

While Eliade’s timescales of the Eternal Return lasted generations, contemporary time is quantified in milliseconds. With the increasing professionalisation of the arts and creative economy, we could imagine Crary’s scenario engineering the perfect creative worker, algorithmically generated by Google and sponsored by AirBnB: a ‘sleepless artist’, constantly in production mode, with no time left to dream. This shift is already reflected by consumer society, where interactivity has begun to overtake passive forms of consumption. Witness, for example, the increasing dominance of the computer games industry over movies, or the live concert over the recorded music product. The ability for the individual to act in realtime, enabled by technological performance, has transformed the society of the spectacle into the society of users. Yet the social and institutional nature of contemporary art evolves along a different timeline.

Perhaps fig-2 exists as the prototype for a physical exhibition format that exists in a state of perpetual renewal, a year-long film that unfolds at a rate of one frame per week, giving both creators and viewers what they need: just enough sleep, just enough novelty, just enough perspective, just enough time. ■

fig-2 ran for 50 weeks in the ICA studio, presenting a new project every week of 2015.

This article is posted in: Articles, Blog, Exhibitions

Tagged with: fig-2, Fatos Ustek, Lawrence Lek, Exhibitions, events, Temporality, Time, Critical Theory, capitalism