In Conversation with Betty Woodman

To coincide with our exhibition Betty Woodman: Theatre of the Domestic, ICA Head of Programme Katharine Stout spoke to Betty Woodman about her innovative work and changes in perceptions of ceramics. The full text of this interview appears in the exhibition catalogue, which also includes essays on Betty Woodman's work by Vincenzo de Bellis, Suzanne Hudson and Stuart Krimko.

The exhibition at the ICA, and at the Museo Marino Marini in Florence, focuses on work from the last 10 years, essentially the decade following your retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It is a period in which you’ve been very experimental, and I wondered if you could say what you regard as distinct during this period and what you see as a continuation of your interests, themes and techniques.

I suppose having the Met show was a liberating experience because there was an enormous audience for it, which gave me a sense of ‘now what do I do?’. We are very fortunate in living both in New York and in Antella, just outside Florence, so I had a chance of going to Italy during the show to stop and figure out who am I; where am I now; what do I want to I do? What I started to do was revaluate - I remember thinking ‘it’s my work, I can copy it if I feel like it’.

"A potter makes something that lives in a situation."

In the 1980s, I had made a series of vases that had a wing, which were based on a small Tanagra figurine that I had seen in Athens. As usual, I started with the process of making, so I changed the scale and began to make what I would now see as a piece of sculpture. I think one of the revelations I had at that point was that a potter makes something that lives in a situation, so it sits on a table or it sits on a shelf, or it can be placed within a domestic environment, whereas a sculptor takes responsibility for how their work is positioned in the world. This opens up a whole other world.

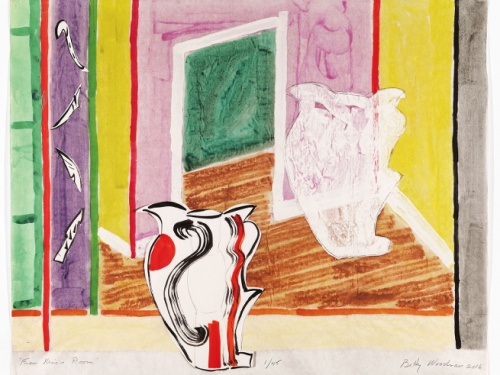

That makes me think about the Rooms, which seem to be about creating your own context for the work, taking as their subject how the ceramic element has a certain utility within the domestic setting.

Yes, this is very related to thinking ‘what do I do now?’ leading to the paintings creating a place for the work to live. I’ve made prints for over 30 years, working with Bud Shark, which led me to use my own work as a subject matter in the paintings. It’s even a step for me to call them paintings. But this is also a part of the ceramics, in that the ceramics are about form, and then it’s about painting on that form and changing the way one perceives its shape by the way it’s painted. This is certainly a part of the history of ceramics. Not so much Asian ceramics, but within the history of European ceramics, and certainly included in what I would call Mediterranean ceramics. In that sense my work is very traditional because it’s about form, but also about painting on the form and changing the way you see it.

What do you find empowering about being an octogenarian and what is challenging in terms of how you’re now regarded in the art world?

It’s empowering because I decided I would just eat ice cream every day if I wish! Within the art world, occasionally people seem to just think you’re courageous when you’re so old just because you can still speak, or put one foot in front of another, so I hope the interest that the art world has in me is because of the art I make rather than my age.

"Being an octogenerian is empowering because I decided I would just eat ice cream every day if I wish."

Also there’s the fact that I’m a woman, and when I started working there weren’t many women artists, in fact the world of ceramics was dominated by macho men but now it’s different.

At the ICA our remit is to respond to the very latest developments in contemporary art and culture, so it’s specifically how innovative the recent work is that we responded to and which Vincenzo de Bellis proposed to the ICA. But of course that is also a result of your extraordinary long career. There are plenty of artists who don’t continue to experiment and move forward with their practice, which is why your work is so interesting for younger generations also.

You should understand each time I have a new opportunity it gives me permission to go ahead, do something new - there is no point in redoing what I already know. What is interesting is that when an artist gets accepted in the market, it’s often for a particular thing, and people can find it hard to accept new work. But you can’t just stay in one place. I don’t understand how an artist can only have one idea.

"You can't just stay in one place. I don't understand how an artist can only have one idea."

Having a huge amount of recognition when you’re young can be an inhibiting thing. I didn’t have that recognition early on so I’m free. I’m not really connected to something that’s defined by the art magazines for example. So it gives me a kind of freedom.

You’ve always gone your own way, and I think that’s the true course of art history, those who have gone their own way rather than followed a trend or a style. There’s such scrutiny, or hyper awareness of everything else and contemporary art is so pluralist, so perhaps it’s harder for artists to just follow their own path.

I think it is, but on the other hand everything is possible, including ceramics. I’ve thought of myself as an artist for 30 years, but the art world has not. ■

Betty Woodman: Theatre of the Domestic runs 3 February - 10 April 2016. Read the full interview in our exhibition catalogue, available in our shop.

This article is posted in: Blog, Exhibitions, Interviews, News, Store

Tagged with: Betty Woodman, Katharine Stout, Betty Woodman: Theatre of the Domestic, interview, Artist Interview, Ceramics, Sculpture, Pottery, Feminism, Women in Art, Woman Artist, Exhibitions, Vincenzo de Bellis, Exhibition Catalogue, ICA Bookshop