Neal Rock

b. 1976, Port Talbot, Wales

2010-2015 PhD Painting by Practice, Royal College of Art, London

1999-2000 MA Fine Art, Central Saint Martins, London

1996-1999 BA Painting, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham

Recent Exhibitions

Solo Shows:

2015 ‘Herm #0415’, Galerie Particuliere, Paris

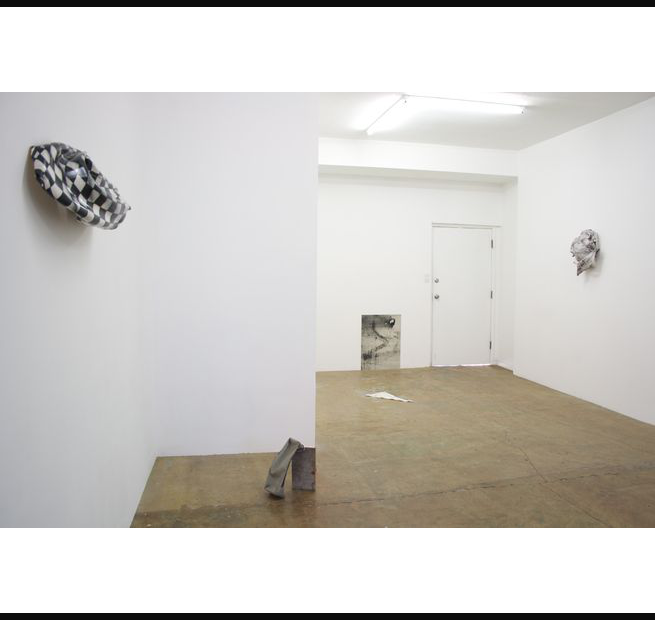

2014 ‘Herm #0714’, Loudhailer, Los Angeles

2012 ‘Velum’, Kunstverein Heppenheim, Heppenheim

2010 ‘Fanestra & other works’, Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles

2009 ‘Fanestra & other works’, New Art Gallery Walsall, Walsall

2004 ‘Polari Range’, Henry Urbach Architecture, New York

Group shows:

2014 ‘John Moores Painting Prize’, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

2013 ‘Slow is Smooth is Fast’, Boetzelaer Nispen, Amsterdam

2007 ‘Jerwood Contemporary Painters’, Jerwood Space, London

2006 ‘Landscape Confection’, Wexner Center / CAM Houston, Ohio and Houston

2005 ‘Extreme Abstraction’, Albright Knox, Buffalo, New York

2004 ‘Expander’, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Awards and Residencies:

2015 Grant Wood Painting Fellowship, University of Iowa, Iowa City

2007 Jerwood Contemporary Painters Joint Prize Winner, Jerwood Space, London

2007 Artist in Residence, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Nevada

2004 British Council Award to Artists, British Council, London

Artist’s Statement

Herms originated in antiquity as boundary markers, found on the peripheries of towns and villages. They were also masked and adorned in Dionysian ceremonies, forming part of their identity as fertility icons. Overlooking these roles is the wing-footed Hermes, whose face and genitals often embellished a herm’s vertical, pillar-like form. The classical philologist Karl Kerényi acknowledged Hermes as the god that most embodied his philosophical outlook. In the build-up to German Fascism, Kerényi revolted against mythic narratives that aligned themselves with national identity.

In this regard he was drawn to journey as a philosophical locus, through which Hermes’ narratives inflected his own thoughts and movements. In the early 1980s, American special effects artist Rob Bottin was employed by filmmaker John Carpenter to create the visual creature effects for his remake of Howard Hawk’s 1951 production The Thing From Another World. Bottin’s effects would significantly contribute to the standard by which prosthetic make-up would develop over the next decade, until the advent of digital technology or CGI. In Carpenter’s The Thing, horror came from within, with each character a potential host for the alien amongst them. Each actor in Carpenter’s production became a prosopon, simultaneously face and mask, through furtive acts of concealment.

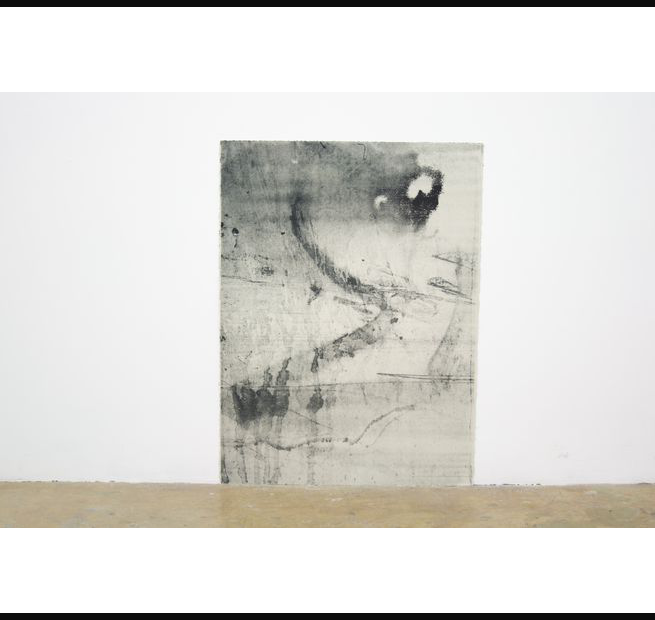

Klaus Wolf Knoebel and Peter Schwarze both attended the Düsseldorf Academy under Joseph Beuys in the 1960s, reacting against an idea of living sculpture that was connected to a Steiner influenced artistic ego. Both sought to sever the umbilical cord that attached artist to object and image. This revolt was to set a lifelong project for Knoebel and endured through Schwarze’s tragically short career. The objects they created were defiant yet porous, owing to a sparse economy of production, yet retaining enough meaning to point outwards - the residue of painting as window.

The horror within is a subject that Carpenter, Schwarze and Knoebel were familiar with. Their musings on otherness were infused with a sense of spirituality in the absence of god or religion. The most direct form of address to this exteriority for Schwarze was the triangle, a simplistic form, yet a continuous pointing outwards, upwards, no longer to a higher presence, but to the vulnerability of an outside where letters clatter.